More Hawaii Schools Qualify for Free Meal Programs but the State May Not Participate

Recent changes to a federal program could allow for a significant expansion of free school meals in Hawaii, but it's unclear if the state will opt in.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

At Ilima Intermediate School, teacher Sarah Milianta-Laffin often sees students standing around the trash cans after lunch, asking their peers if they can eat the leftovers off their lunch tray.

Milianta-Laffin purchases around $500 worth of snacks at the start of each school year to keep in her classroom, anticipating that some students will need a granola bar to get through class if their families can’t afford school meals.

“Meals should be things that we just give automatically, and we know we see better results,” Milianta-Laffin said. “Attention span is better when kids are not hungry. Anxiety is lower, because you’re not worried about where your next meal is coming from.”

Recent changes to the National School Lunch Program could allow a major expansion in the number of Hawaii schools that offer free meals to all students. But it’s unclear how many of schools will take advantage of the Community Eligibility Provision program, which provides schools in high-poverty areas with federal funds meant to subsidize the cost of offering free breakfast and lunch to all families.

Before recent changes to the program, schools where 40% or more of students were low-income or had high-needs could qualify for the CEP. That includes students who are homeless, in foster care or enrolled in federal initiatives such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Under recent changes to the program, the qualifying threshold has dropped to 25% of a school’s student body. According to a database from the Food Research And Action Center, which uses data from the 2022-23 school year, 83 new schools in Hawaii could enroll in the CEP.

Nicole Woo, director of research and economic policy at the Hawaii Children’s Action Network, said hungry students can’t learn. Even if families qualify for reduced-price lunch, they may still struggle to cover the remaining costs of school meals and could benefit from the CEP expansion, she added.

“The benefits are clear,” Woo said. “We certainly hope the Department of Education and charter schools will take advantage of this new rule to get free meals to more kids.”

But, Woo acknowledged, making this change might be easier said than done.

A Financial Roadblock

Currently, 106 schools in Hawaii offer free meals to all students under CEP.

Even with CEP’s expanded eligibility, Hawaii families may not see free lunch offered at their schools right away, said Daniela Spoto, director of anti-hunger initiatives at Hawaii Appleseed.

According to the FRAC database, 17 eligible Hawaii schools chose not to adopt CEP in the 2022-23 school year.

The Department of Education is still analyzing how recent changes to the CEP rule will impact Hawaii schools, said deputy superintendent Tammi Oyadomari-Chun.

One question the department faces is whether all Hawaii schools can now qualify for CEP. The federal government allows entire districts to participate in CEP, as long as their schools have an average of 25% or more of low-income students.

Hawaii has a single statewide school district, but the DOE is still trying to determine whether the state can group together all schools and whether the district would meet the 25% threshold, Oyadomari-Chun said. Even if this is a possibility, the decision could be an expensive one for the department, Oyadomari-Chun added.

CEP schools receive federal reimbursements to help to cover the cost of offering free breakfast and lunch to all students. But schools with fewer low-income students receive less federal support helping to cover the costs of those meals.

The responsibility falls to the school district to cover the remaining costs of offering free meals at CEP schools, Oyadomari-Chun said. The department is still determining what these costs might be for next year, she added.

Last year, the department estimated that, even with federal reimbursements, it would cost roughly $64 million a year to provide free meals to all students, although the final number could vary based on students’ participation in school meal programs and the costs of labor and food.

“We really want to feed our kids,” Oyadomari-Chun said. “We really would love for the whole state to be part of CEP, but it does have a cost to the state that we have to analyze.”

Hawaii isn’t the only state weighing the costs and benefits of expanding schools’ participation in the CEP.

Some states, like Oregon and Washington, have already set aside funding to cover the costs of providing free lunch under the CEP, said Crystal FitzSimons, the director of school and out-of-school time programs at FRAC. When more state and federal funds are available to cover the costs of meals, schools and districts are more likely to take advantage of the CEP, she added.

“There’s definitely a variation in the take-up rate based on the amount of federal reimbursement the school would receive for their meal,” FitzSimons said.

Schools under the DOE would not have to use their own budgets to cover the costs of providing free lunches under the CEP, Oyadomari-Chun said. Instead, she added, the department would request necessary funding from the Legislature in the spring.

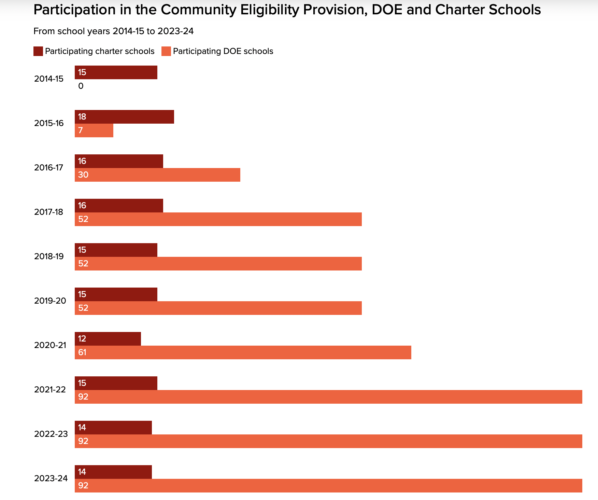

But charter schools, while also eligible for the CEP, have to use their own budgets to cover whatever costs the federal government won’t reimburse for school lunches. While the number of DOE-operated schools in Hawaii participating in the CEP grew from seven to 92 between the 2015-16 and 2023-24 school years, the number of public charter schools dropped from 18 to 14.

For Ka ‘Umeke Ka’eo, a charter school in Hilo, enrolling in the CEP initially seemed like a straightforward decision, said director of operations Louisa Lee. The school knew many of its families could benefit from a free lunch, and Lee hoped the federal reimbursement rate would offset the cost of participating in the program.

But participating in CEP cost the school approximately $120,000 to $150,000 a year, she said. The school considered withdrawing from the program but has continued its participation because families needed free lunch more than ever due to hardships from the Covid-19 pandemic, she said.

“I would say that our CEP plans are year to year,” Lee said. “It’s year to year for as long as we possibly can, or until we find another option.”

Policy Possibilities

The push for free meals in Hawaii schools isn’t new. Last year, three bills in the Legislature called for the state to make food more accessible to students, from providing universal free meals to establishing a subsidy for students who do not qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. However, none of these bills passed into law.

Rep. Mahina Poepoe introduced one of the bills, which would have offered free breakfast and lunch for all students beginning in the 2023-24 school year. Poepoe said she hoped to fill a need the federal government temporarily addressed during the height of the pandemic, when schools offered free lunch to all families.

By offering free meals to all students, schools can help to reduce the stigma around free or reduced-price meals, Poepoe said. She hopes the recent expansion of CEP-eligible schools can help reduce the cost of establishing a universal free school meal program.

“I’m very hopeful that the rule change will make legislation more palatable in the upcoming session by further reducing the cost,” Poepoe said.

Oyadomari-Chun said the department would be interested in seeing similar legislation introduced this year, but would need to consider the financial implications of the proposal.

Sarah Fukuzono, an educational assistant at Kanoelani Elementary School, said providing free meals to all families would ensure that her students are ready to learn and have access to nutritional foods. She recalled how, last year, she would bring eggs to one of her students in the morning, knowing that he would come to school cranky and without breakfast.

“If the student is hungry, I’m not going to get any work out of them,” Fukuzono said. “But if we have a general baseline of, these kids have eaten breakfast, these kids have eaten a nutritious lunch, then we can move on to things like learning.”

Civil Beat’s education reporting is supported by a grant from Chamberlin Family Philanthropy.

Civil Beat’s community health coverage is supported by the Atherton Family Foundation, Swayne Family Fund of Hawaii Community Foundation, the Cooke Foundation and Papa Ola Lokahi.

This story was originally published in Civil Beat.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)