Fewer School Meals: Data From Top Districts Reveal 7% Decline in Students Accessing Lunches Last Year

As districts adjust to the absence of federally funded free school meals, experts say statewide policies are needed to improve student participation.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The number of students receiving school meals fell dramatically in the 2022-23 school year as federally funded pandemic meals expired, according to a new report from the Food Research and Action Center.

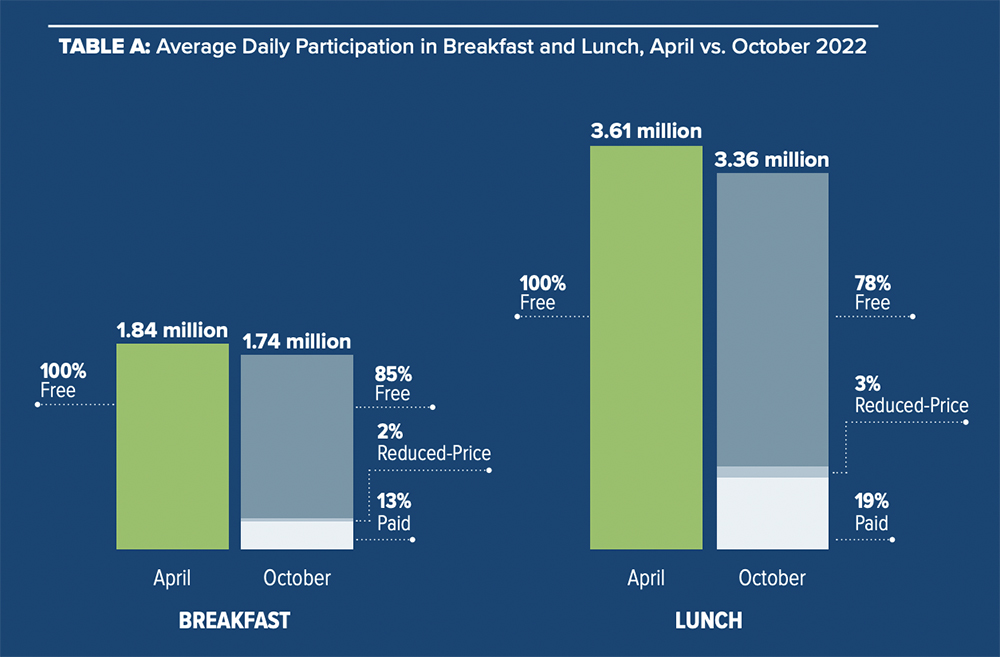

Of the 91 large school districts surveyed, accounting for more than 6.5 million students, participation in school breakfast and lunch decreased by more than 100,000 and 250,000 students respectively.

In particular, school breakfast participation dropped from 1.84 to 1.74 million students, and school lunch participation dropped from 3.61 to 3.36 million students — a decrease of 5% and 7% respectively.

“The return back to normal school meal operations, which a number of the districts that participated in the survey had to do, really did negatively impact school nutrition operations,” Crystal FitzSimons, director of school and out-of-school time programs at the Food Research and Action Center, told The 74.

Experts said participation declines came from young families whose children entered school during the free meals for all era unaware of how and where to fill out the proper forms when the federal program expired.

Experts also pointed out flaws in the free or reduced-price meal eligibility system some districts had to default back to.

For instance, a student from a household of three is eligible for free lunch if they made $32,318 or less in annual income and for reduced-price lunch if they made $45,991 or less, according to federal guidelines set for the 2023-24 academic year.

“It’s really tone deaf to the fact that people who might be above the free or reduced-price category could still be struggling middle class families,” Joel Berg, chief executive officer at Hunger Free America, told The 74.

Large districts were defined as having an enrollment greater than 7,000 students — from more than 7,000 students in California’s Inglewood Unified School District to nearly 1 million in the New York City Department of Education.

Other districts include Los Angeles Unified School District, San Diego Unified School District, Chicago Public Schools and District of Columbia Public Schools.

Of the 91 districts surveyed, five were in states that have independently funded free school meals for all and 28 implemented the Community Eligibility Provision, or CEP — a program that allows schools with high poverty rates to provide free breakfast and lunch to all students.

The remaining 58 districts went back to their tiered eligibility system where students had to qualify for free or reduced-price meals — thus contributing to the drops seen in student participation.

FitzSimons said the drops were not as dramatic as they could have been because a handful of the districts surveyed prioritized maintaining pandemic-era meal operations as much as they could afford.

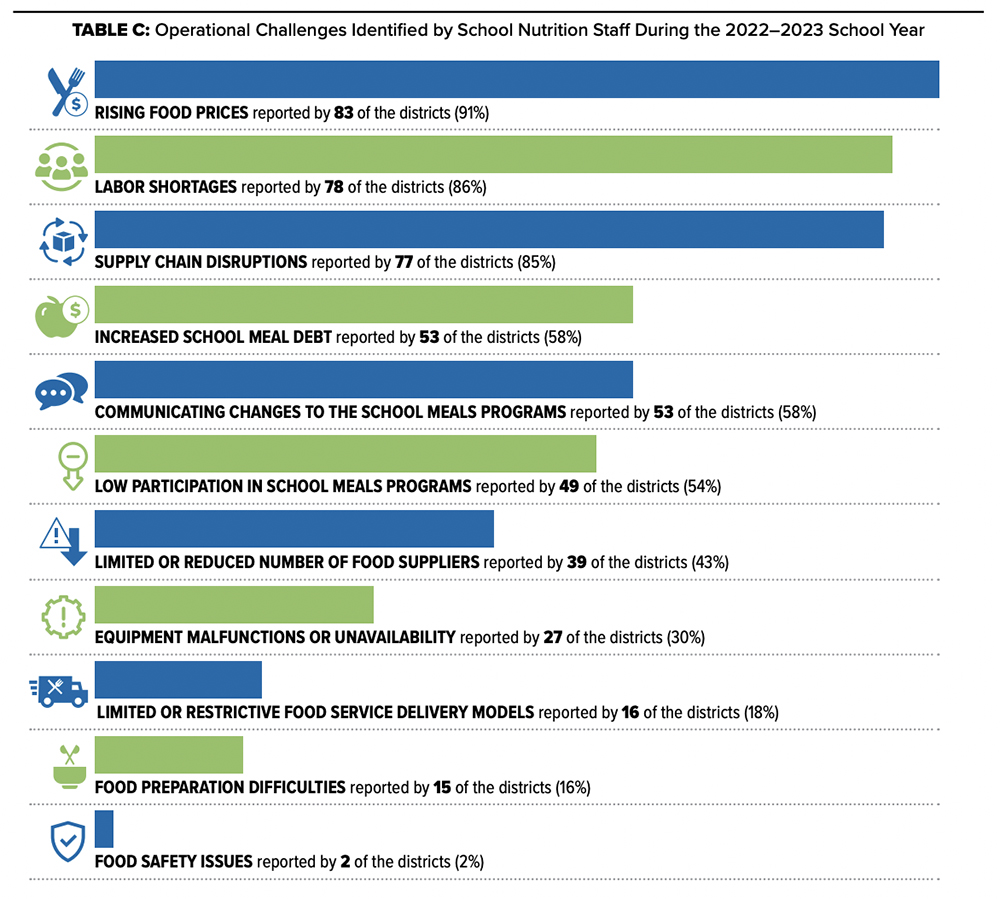

However, FitzSimons noted rising food prices, labor shortages and supply chain disruptions among other operational challenges contributed to the struggle districts faced to provide students’ healthy school meals.

“School districts were really struggling with the changes and with so many of the operational challenges that had been taking place throughout the pandemic,” FitzSimons said.

91% of districts reported rising food prices as their topline issue, in addition to 86% that struggled with labor shortages and 85% that struggled with supply chain disruptions.

Other operational challenges include increased school meal debt, communicating changes to the school meal programs when the federal program expired and low student participation.

Matthew Essner, vice president of state nutrition at LINQ, said problems communicating changes to the school meal programs was a widespread issue.

“When schools went back to the traditional meal setting, access and people even understanding that they were required to fill out those forms was a bit confusing,” Essner told The 74.

FitzSimons added how labor shortages and the number of school lunch lines “negatively impact kids being able to get food quick enough.”

FitzSimons also noted how supply chain disruptions impacted schools’ ability to serve a variety of healthy school meals, which decreased students’ desire to participate in the meal programs.

“[Healthy school meals] generate excitement, particularly with older kids, because we do see participation in the programs decrease as kids get older,” FitzSimons said.

So far California, Colorado, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico and Vermont have acted to independently fund free school meals for all students.

As momentum grows, FitzSimons said statewide legislation as such is the most viable way to ensure every student has access to healthy school meals.

“We need to be looking at Healthy School Meals for All as the way to operate school nutrition programs,” FitzSimons said. “It changes the whole culture of the school cafeteria.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)