Los Angeles Teachers to Strike in January If Union Doesn’t Get ‘a Dramatically Different Approach’ From School District

Updated Dec. 27

United Teachers Los Angeles will strike Jan. 10 if L.A. Unified doesn’t take “a dramatically different approach” to negotiations, the union announced Wednesday.

“[By] refusing to invest in our schools, the district has disrespected our students and disrespected us,” Alex Caputo-Pearl, the union’s president, said at a morning news conference. “We’ve reached the point where enough is enough.”

The announcement came the same day a state board issued a complaint against UTLA for “refusing to bargain in good faith,” and one day after the release of a third-party fact-finding report — the last step in the labor negotiations process before the union can legally strike.

The non-binding report by neutral state-appointed mediator David Weinberg recommended that the district’s 6 percent raise proposal be adopted: 3 percent retroactive for 2017-18 and 3 percent for 2018-19. The two other members of the fact-finding panel — a union and a district representative — both agreed with Weinberg’s salary recommendation.

Weinberg also validated that L.A. Unified “does have financial limitations that must be balanced” and advised the two parties to drop or scale back most of the 21 unresolved contract disputes.

The report did, however, support some of the union’s demands, including designating funding to lower class sizes and to hire more nurses, counselors, and librarians. These demands have been central talking points for UTLA, along with restrictions on charter schools and standardized testing.

Though meant to help L.A. Unified and the teachers union resolve nearly two years of embattled contract negotiations, the report’s release added fuel to the fire, with the union saying that L.A. Unified had manipulated the findings and lied about UTLA agreeing to a 6 percent raise. The union is filing another unfair-labor-practice charge in relation to that statement.

“We’ll need to see [a] willingness to engage the issues that are fundamental to building a thriving school district, like class size, staffing, regulation of charters” in order to avert a strike, Caputo-Pearl said.

L.A. Unified emphasized in a statement Wednesday that it “does not want a strike — which only UTLA can authorize — because a strike would harm students, families, and communities most in need.” Superintendent Austin Beutner had told reporters at a Tuesday briefing that the district “really want[s] to reach a resolution” with its labor partner.

“It’s time that we have an honest conversation, authentic bargaining … because our students aren’t waiting. Our families aren’t waiting,” Beutner said. “This is not some Netflix show [or] drama, this is about real people who we have to serve each and every day.”

District officials have claimed for months that Caputo-Pearl has sabotaged negotiations and denied the district’s grim financial projections in favor of a strike. The State of California Public Employment Relations Board, which appointed Weinberg, issued a formal complaint Wednesday against UTLA for “refusing to bargain in good faith” with L.A. Unified and for reportedly “retract[ing] its support for a 6 percent salary increase.”

Key points of the mediator’s report include:

1 Salary

The three panel members agreed that the district’s 6 percent raise is appropriate. But Caputo-Pearl said Wednesday that UTLA is still calling for a 6.5 percent salary raise retroactive to July 2016.

The average teacher salary package is $105,000, including health and other benefits, according to the district. Teachers are assigned 182 days a year.

In line with salaries, the report also recommended L.A. Unified’s proposal for new incoming teachers to wait longer to be eligible for retiree health benefits. The district wants to add two years for new teachers, so that a teacher’s age plus his or her years of district service would total 87 years — a “Rule of 87” compared to the current “Rule of 85.” Retiree health benefits represent “an ongoing balance sheet problem” for L.A. Unified, according to the report.

The UTLA panelist, Vern Gates, opposed this suggestion, claiming that L.A. Unified hadn’t added the Rule of 87 until its Sept. 25 contract offer — after bargaining sessions had ended. Adding “something as contentious as health benefits” late in the game “is at least an indication of bad faith bargaining, and certainly a recipe to prevent a settlement,” he wrote.

2 Class sizes

The report called class size “essential to the resolution of this dispute,” and all three panelists supported deleting a contract provision that lets the district increase class sizes as a cost-saving measure. The report also advised the district to designate the equivalent of a 1 percent to 3 percent salary increase “to recruit additional teachers and staff to reduce class size and increase access to other professional services.”

The district and UTLA would still have to settle on a new framework for navigating class sizes, however. Each 1 percent equates to about $29 million, a district spokeswoman told LA School Report in an email Wednesday. She added that the district previously allocated $30 million in the contract for class size reduction and “remains willing” to do so as part of a resolution.

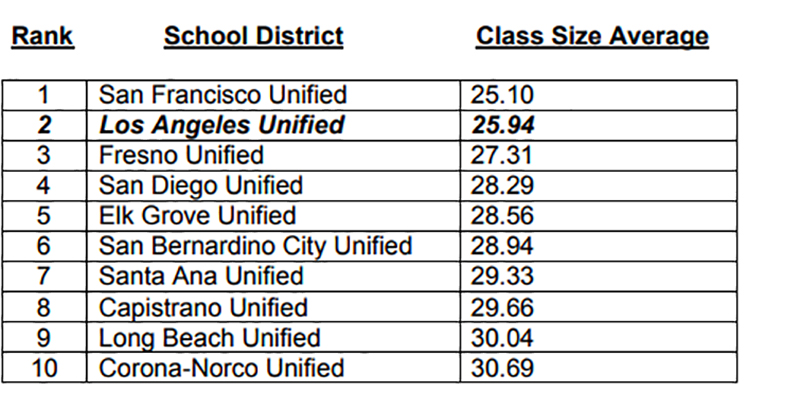

District representative Adam Fiss warned that if the provision is deleted, “it will be important to negotiate safeguards that allow for deviation … during times of economic duress.” He also referenced data from the California Department of Education showing that L.A. Unified has the second-lowest average class size — about 26 students — among the state’s 10 largest districts.

Under the current agreement, though, class sizes for middle schoolers and high schoolers can creep into the 40s.

3 Shared decision making

The neutral report recommended tabling UTLA’s request for local school leadership councils, which would wield significant influence in professional development for employees and the spending of school-based discretionary funds. UTLA “is unlikely to convince the district at this time to develop a shared decision making model given the lack of trust between the parties,” the report stated.

Weinberg also advised dropping the union’s demand that teachers get a vote on converting schools to magnets.

Gates, the union representative, opposed both of those recommendations, noting that the district’s “claims to be a proponent of local control” contrast with its rejection of these kinds of demands. Beutner is preparing to release a “Reimagining” plan, which reportedly would split L.A. Unified into about 32 autonomous districts to empower local leaders, teachers, and parents. The fact-finding report’s release delayed the plan’s announcement, initially slated for this week.

The union has already called the coming plan by Beutner a ploy to expand charter schools. Beutner “isn’t moving” on negotiations “because there’s a bigger [privatization] agenda for him,” Caputo-Pearl said Wednesday.

The district has denied this, stating that “at no time has the Board of Education or Superintendent mentioned any support for ‘privatization.’”

4 State testing

The report didn’t fully back UTLA’s proposal to give teachers “academic freedom” to decide whether to administer standardized tests beyond what state and federal law requires. It instead recommended a pilot program at an “appropriate number of schools at each [school] level.”

Limiting the district’s discretion with testing “should be carefully circumscribed,” district representative Fiss wrote. UTLA panelist Gates pushed for the full implementation of UTLA’s demand, writing, “Every hour spent on a needless District required test is an hour that could’ve been spent on instruction.” UTLA has stated previously that L.A. Unified spends millions annually on non-mandated state testing.

Pilot program recommendations were peppered throughout the neutral report. Weinberg also proposed piloting L.A. Unified’s wish for a “highly effective” category in teacher evaluations at “an appropriate number of schools at each level, total of 5-10.”

A strike in the making

A teacher strike was already looking imminent before this week.

On Dec. 4, UTLA handed out strike kits to its chapter chairs at more than 800 school sites and boycotted staff meetings at schools. Protesters shut down a school board meeting on Dec. 11, and thousands of people participated in the “March for Public Education” in downtown Los Angeles last weekend. UTLA cited more than 50,000 marchers, though a formal count hasn’t been confirmed.

The district, meanwhile, has distributed at least 115,000 copies of a parents guide titled “Preparing for a potential strike” to schools. It has also encouraged parents to volunteer.

If the union — which has more than 30,000 members — strikes Jan. 10, it would come after just three days of class after the winter break.

The work stoppage would affect about 480,000 K-12 students across more than 1,000 schools. L.A. Unified has emphasized that schools would remain open with instruction from “qualified L.A. Unified staff,” such as administrators.

Parents’ reactions varied on news of the strike. “We will stand firm with our teachers,” Accelerated Schools parent Hilda Rodriguez-Guzman said at UTLA’s news briefing Wednesday. “Because our kids deserve the best-quality public education here in Los Angeles.”

Parent Kathy Kantner, however, told LA School Report on Wednesday that she was “very disappointed” with UTLA’s announcement. The fact-finding report had given her hope that negotiations were possible.

“I’m not sure how meaningful the time will be if my child goes to school” during a strike, she said. “I’m still going to wait and see. I’ll see what that first day would look like and take it from there.”

There were 22 bargaining sessions between April 2017 and July, when the union declared an impasse. There were then three mediation sessions between September and October. During that span of time, “almost no progress” was made in negotiations, the neutral report stated. The fact-finding panel was seated in November.

At the heart of the contract disputes have been two competing narratives on the district’s financial ability to meet the union’s demands. On one hand, the county has called L.A. Unified’s finances “alarming,” projecting its reserves to drop from $700 million next fall to $76.5 million in 2020-21 — barely over the 1 percent reserve required to stave off a county takeover.

The district has maintained that accepting UTLA’s contract would “immediately bankrupt” it. Beutner has proposed that the two sides rally for more funding in Sacramento, which provides 90 percent of the district’s annual budget, which is about $7.5 billion this school year.

Caputo-Pearl countered Wednesday that “UTLA has been relentless” in pursuing state money. The union claims that L.A. Unified is hoarding a “record-breaking” $1.8 billion in reserves while class sizes balloon and about 40 percent of schools have a nurse only once a week.

This week’s fact-finding report could not resolve the discrepancies in reserve estimates.

The fact that the two sides haven’t been able to agree on L.A. Unified’s fiscal reality “is very problematic,” Aaron Garth Smith, an education policy analyst for the right-leaning Reason Foundation, told LA School Report this week. “At the end of the day, everyone is going to suffer, including teachers and students. Having more obligations and spending more money is only going to make that [fiscal] hole even deeper.”

Two days after his news conference announcing a strike date, Caputo-Pearl held another news conference, this time to call for a halt to new independent charter schools in L.A. Unified. The call for a cap is not part of the union contract negotiations, but Caputo-Pearl said he is bringing it up because “it’s out there in the conversation right now.” He cited Gov.-elect Gavin Newsom, who “has looked into whether we need to pause,” and the new state superintendent of public instruction, Tony Thurmond, “who has proposed a moratorium on charter growth.”

Esmeralda Fabían Romero contributed to this report.

This article has been updated with Caputo-Pearl’s Dec. 21 news conference calling for a cap on charter schools in the district.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)