‘Just Above Water’: As Hallowed D.C. Summer Youth Employment Program Preps to Go Virtual for First Time, Employers Rush to Create Meaningful Experience for 10,000 Students

Marje Hines spent last year’s D.C. summer youth employment program working as a summer camp counselor. She’d read books with rambunctious youngsters or take them outside to doodle with chalk and play basketball.

Hines, 19, is working for that camp again this summer. But she won’t be seeing her kids in person, and she’s having trouble picturing what this year’s camp season will be like when the six-week program starts June 22.

“How is that going to happen? How are we all going to be on the computer? Are the kids going to want to sit and talk?” wondered Hines, a rising junior majoring in early childhood education at Delaware State University who is currently back home in Ward 5. “It’s still running through my head.”

Students like Hines will be participating in D.C.’s hallowed Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program, in its 41st year after Mayor Muriel Bowser, an advocate for the program, preserved its $18.5 million funding in the current budget.

But with 90 percent of youth jobs forced to go virtual for the first time ever because of the pandemic, local employers partnering with MBSYEP are in a mad dash to reimagine a meaningful summer experience for the city’s 10,000 14-to-24-year-old participants — many of whom are relying on the program, especially during the economic crisis, for job experience.

“All of us are just above water, we’re just treading” for now, said Mukta Ghorpadey, D.C. alumni services director for Urban Alliance, an MBSYEP employer that provides career opportunities for under-resourced youth. But the community “is coming together and figuring it out together.”

Cities nationwide are facing a similar task. Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston are transferring much — or all — of their youth summer jobs online. In other places, like New York City, the long-standing program’s funding was slashed, though Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Thursday that the city will create a smaller-scale summer jobs initiative.

In D.C., the possible solutions vary by employer. Urban Alliance is crafting a professional development curriculum youth can complete instead of a job at sites like hospitals, federal government offices and summer camps. Another nonprofit employer that places its students at local government offices is brainstorming research projects and community surveys. And a medical center is tossing around ideas such as hosting virtual seminars, though without robust guidance from the city, it says, it’s been difficult to establish a framework.

“Everybody wants to figure out how to do this and how to do it well,” said Robyn Lingo, executive director of Mikva Challenge DC, a nonprofit that promotes youth civic engagement. “There’s a real commitment to serve students.”

The importance of MBSYEP

Managed by the D.C. Department of Employment Services, the youth program is one of the largest in the country, and it is a career-building, economic lifeline for many D.C. kids, normally offering hands-on job training across sectors. Local employers apply to host youth, who earn $6.25 to $14 an hour.

Program employers said keeping MBSYEP running is more vital than ever, as remote learning, an economic crisis and social unrest have thrown many students’ lives off-kilter — especially those in communities of color. Last year, African-American youth accounted for 91 percent of participants, according to an independent evaluation of the program. Eighty-four percent either spent or saved their money for school-related purposes or other necessary expenditures, such as clothes and food.

It’s “a crucial stability” for students, Lingo at Mikva Challenge DC said. “It’s a crucial economic stability, it’s a crucial public health stability, it’s a crucial learning stability.”

Participants like Hines and D.C. rising senior Jordyn Middleton said they still want to make the most of the opportunity.

“I still want to be excited for the job,” said Middleton, who attends Benjamin Banneker Academic High School and just learned Thursday she’ll be working for D.C.’s deputy mayor for education. “The ability to still learn from my work … is important to me.”

Jumping from hands-on work to virtual opportunities

Last summer’s job set a high bar for Middleton.

Mikva Challenge had placed the aspiring attorney in D.C. Councilman David Grosso’s office. After commuting in on the red line, she’d put together research memos on topics like affordable housing and gentrification, and regularly weighed in on education issues youth were thinking about.

Her role “wasn’t something that was sugarcoated or downplayed,” she said. “I was treated like everyone else was.”

Lingo at Mikva Challenge DC — who’s helping assign Middleton and at least 12 other students to offices of D.C. council members, the attorney general and others — hopes to keep youth this summer equally engaged, and she says the plans so far include having them survey peers citywide “on how distance learning went this spring and what students need as schools start in the fall,” using tools from social media to SurveyMonkey.

Middleton is awaiting more fleshed-out details. If possible, she says, she’d like to designate some time to conducting research and outreach that amplifies the voices of those experiencing homelessness and struggling with their mental health.

“As a minority, as a woman, as an African-American woman, sometimes … [people] feel like they’re being listened to but not understood,” she said.

Urban Alliance has also had to recalibrate. Ghorpadey, the D.C. alumni services director, had placed all 55 of her MBSYEP youth at job sites, from federal government offices to hospitals and summer camps, before the pandemic hit. Then about 40 positions fell through.

To keep those students in MBSYEP with a paycheck, Ghorpadey and her team are crafting a curriculum for them to complete instead: six weeks of professional development training that will include “a lot of project-based learning, a lot of virtual networking practice and different skills building,” she said. And rather than setting firm work hours — usually 20 to 30 hours a week — the focus is now on completion.

Especially now, “a lot of my young people have to take care of kids, or take care of families, or work another job,” she said.

Employers are allowed to come up with their own online curriculum, pending approval from the program. MBSYEP’s own virtual curriculum is also available.

Ghorpadey sees a silver lining with this new online format — getting youth acclimated to online jobs and skill sets, like virtual interviewing. But she added that it’s premature to say whether such a curriculum can effectively substitute for in-person learning.

“It’s hard to say that if they’re now doing virtual programming with me and building skills on Microsoft Excel, what of that can compare to being able to actually have some type of shadowing experience at a hospital?” she said.

Hines, the summer camp counselor, is one of the few placed through Urban Alliance whose position didn’t fall through. Having to be remote is still “heartbreaking,” she said, but she hopes this summer can be beneficial for her as a teacher-in-training — especially if schools maintain some element of remote learning over the next few years.

“If things like this happen in the future, I want to know how to prepare myself,” she said.

For Kony Serrano, senior youth development worker at Mary’s Center, there wasn’t a question of whether the medical center would still participate in MBSYEP this summer. The program has a special place in her heart — Serrano had been in the program as a teenager — and Mary’s Center’s partnership with MBSYEP runs deep: 17 years.

It brings students “closer to having that sense of community,” she said.

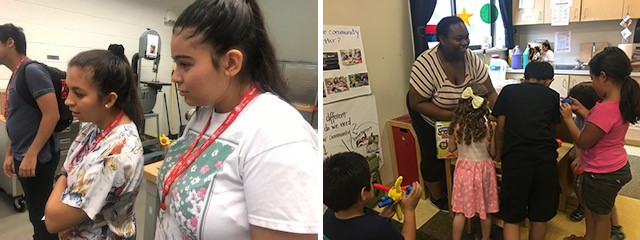

Typically, 50 to 70 MBSYEP participants would work across Mary’s Center’s departments, doing everything from helping nurses take patients’ temperatures to attending development events to learn about fundraising. The center had selected 42 students as of Tuesday, and it is considering holding virtual seminars that spotlight “different people in different careers within our clinic to give [teens] talks about how they got there, what type of education they needed, what type of training they needed,” Serrano said.

The center, however, remained unclear as of last week on how much autonomy it has over its virtual programming. Guidance has been slow coming, Serrano said.

Luckily, employers and students said, each week is bringing more clarity. The D.C. Department of Employment Services is tweeting updates, and youth and employers are encouraged to check their online portals for more information. A spokesperson noted that all MBSYEP participants would receive placement once they completed an online orientation, which ran through Sunday.

Ghorpadey says that considering the circumstances, the process is good enough.

“Nobody has navigated this before,” she said. “So we just have to do what we can. … It’s getting better every day.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)