2023 Test Scores Show No Major Progress for Indiana Third Graders

One in five Indiana third graders will need additional support to build their reading skills, new test results show.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

One in five Hoosier third graders continue to struggle with foundational reading skills, according to new standardized test results released Wednesday.

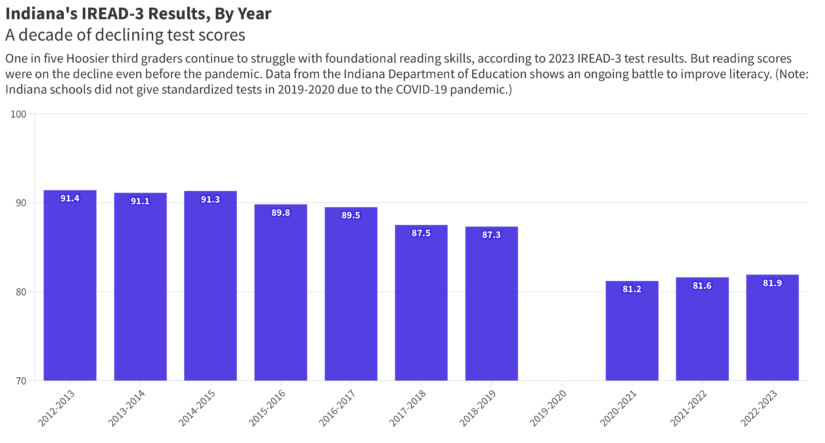

Data from the Indiana Department of Education (IDOE) shows 81.9% out of the roughly 82,000 third graders at public and private schools in Indiana passed the 2023 Indiana Reading Evaluation and Determination, also called the IREAD-3 test. Tests were administered statewide this spring and summer.

The results are nearly stagnant from the last academic year, when 81.6% of students’ scores indicated reading mastery. The state education department’s goal is that 95% of students in third grade can read proficiently by 2027. As of this spring, 242 schools have reached that goal — an increase from 210 schools a year ago.

Latest results indicate Indiana’s younger students also still lag behind pre-pandemic reading fluency.

Scores are 5.4% behind the results from the 2018-2019 school year, which is the last data set available prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Indiana schools did not give standardized tests in 2019-2020 due to the pandemic.

Reading scores were on the decline even before the pandemic, however. The Hoosier literacy rate has seen a significant drop from Indiana’s high of 91.4% in 2012-13.

In total, about 13,000 Hoosier third grade students — more than 18% of those in the state — will need additional support to build their reading skills to meet grade-level reading standards, according to state officials. A student who does not pass the IREAD-3 test typically must receive remediation, or risk being retained in third grade.

The IREAD-3 scores roll in as the state shifts its literacy instruction to implement the science of reading as part of an effort to improve students’ reading skills.

“We have to shoot high,” Indiana Secretary of Education Katie Jenner told the Indiana Capital Chronicle on Wednesday. “We have a goal set — we know it’s aggressive, and we are following that with some very aggressive tactics to support our current and future teachers to try to engage our parents and families in getting kids to school.”

“It has to be everyone together to make sure kids can read,” she continued.

Disparities persist

Black and multiracial students had the highest percentage gains, while Indiana’s Hispanic students recorded declining pass rates from last year.

About 65.6% of Black students and 64% of English language learners passed the multiple-choice IREAD exam in 2023 — slightly more than in 2022, but still nearly 10% fewer than in 2019.

Hispanic students’ pass rates dropped from 69.8% in 2022 to 68.9% in 2023.

Reading proficiency additionally improved overall for third grade students receiving free or reduced-price meals by nearly a percentage point.

Special education students had the greatest progress boost — an increase of 2.1% from 2022, for a total of 54.9% passing the IREAD-3 exam in 2023.

Earlier this year, research from Harvard and Stanford universities showed that Indiana students lost nearly six months of learning in math and over four months in reading as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other Spring 2023 tests showed that only 30.6% of Hoosier students in grades 3-8 passed both the math and English sections of ILEARN. While the standardized test results were a slight increase compared to 2022, passing scores trailed more than six percentage points behind 2019′s pre-pandemic pass rates.

“It has to be an all-hands-on-deck approach. Schools cannot do this alone,” Jenner said during a monthly State Board of Education meeting Wednesday, talking about an “urgent” need for coordinated statewide literacy efforts. “We’re going to do everything we can, everything in our power, to make sure kids can read, but we need everyone at the table, helping us with this — helping us get kids to school, helping us provide the other out-of-school supports that may be needed.”

Board member Scott Bess emphasized that some of the students struggling the most with reading “are also some of our fastest growing demographic populations in the state.”

“Indiana’s economy depends on these subgroups accelerating and catching up,” Bess said. “Because without that, as that population changes across the state … there’s no hope.”

Other board members mentioned an ongoing lack of transportation for some Hoosier students — a barrier to getting to and from school.

But Pat Mapes, another board member, doubled down that the latest scores are partly a result of too few kids actually showing up to school.

“We’ve got to get better at attendance … our parent need to make certain their kids are present in the building,” he said. “Not when they’re ill — that’s something different. But we’ve got a lot of kids that just say, ‘I don’t want to go to school today,’ and nobody’s making them go to school. Not being in front of the classroom, with teachers, is detrimental to their work.”

Board member Katie Mote additionally suggested a partnership with the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council or collaborations with local judges to try a “carrot and stick approach” to compel students to get into the classroom.

Jenner said state education officials “have to lean in on that attendance conversation,” although she noted that it’s currently up to each Indiana county prosecutor to decide how to enforce truancy laws.

She told the Capital Chronicle that state leaders want to analyze statewide attendance data before making specific recommendations or calling on lawmakers for help in the 2024 legislative session. Even so, Jenner said state data shows that students who attend at least 169 days of the 180-day school year are “significantly” more likely to do well in school and score higher on standardized tests.

Will new science of reading initiatives be enough?

State lawmakers passed multiple new bills in the 2023 legislative session as part of an ongoing effort to reverse learning loss and increase academic proficiency.

That included a GOP-led effort to require schools to use “science of reading” curricula approved by the state education department by the start of the 2024 academic year.

The phonics-based literacy approach incorporates phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Education experts say it gives students the skills to “decode” any word they don’t recognize.

The state is also banning schools using the “three-cueing model,” which encourages students to make educated guesses at words using context clues. The model has been largely disproven by cognitive scientists but is still used by schools in Indiana and around the country.

The ongoing curriculum overhaul to center student learning and teacher training methods to the science of reading has so far included a pilot program, involving 54 schools around the state. During the 2022-2023 school year, literacy instructional coaches were placed in each school to help teachers train and put into practice science of principles.

The IREAD-3 pass rate among those schools was nearly 72% in 2023 — almost 2 percentage points higher than in 2022. Some schools that have already adopted the new curriculum saw even larger gains, however.

The continued science of reading shift will be paid for from a $111 million fund created late last year by the state and the Lilly Endowment, which donated $60 million to K-12 science of reading efforts and $25 million to teacher preparation programs. The state has chipped in $26 million from the state’s federal COVID relief dollars.

Additionally, Indiana’s next biennial budget adds up to $20 million in each of the next two years for education department’s efforts on science of reading.

Jenner said one of the most important steps forward is ensuring that Hoosier teachers have science of reading training — but not just for elementary educators.

Middle school and high school teachers — many of whom have not received special training in foundational literacy — are increasingly having to teach those skills to students who are unable to read.

“Every single educator, when they go into the classroom, they want to make a difference for kids,” Jenner told the Capital Chronicle. “We have to do everything we can to support our current teachers in in learning those strategies.”

Still, Jenner cautioned that it takes “more than a textbook” to get kids back on track. IDOE chief academic officer Charity Flores said a major turnaround for statewide literacy rates could be years down the line.

“We know that in many cases — for changes to typically occur once science of reading is inserted into a school building — that can take five to seven years. It takes time to train all of the educators, understand how that impacts curriculum and instruction, and how that impacts assessment. To see significant changes in the course of a year is typically very rare,” she said. “But for us to see some of these early indicators in some of the populations that we were really targeting with this effort is really exciting.”

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: [email protected]. Follow Indiana Capital Chronicle on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)