A Hearing on Learning Loss and a Preview of the Election Battle to Come

At House hearing Wednesday, Republicans blamed unions, while Democrats called proposed GOP budget cuts ‘ironic.’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Republicans and Democrats agree that pandemic-related school closures contributed to an academic crisis — what one witness during a Wednesday Congressional hearing called a “generational tragedy.” But debate over the necessity of the extended shutdown and ways to help students recover still breaks down along partisan lines.

Members of the House’s GOP majority and their witnesses used the education subcommittee gathering to lay blame on the teachers unions for delays in reopening during the 2020-21 school year.

“This whole thing was like a jagged little pill,” said Florida Republican Aaron Bean, using a ‘90s music reference to describe the slow return to in-person learning.

Democrats, meanwhile, argued that extreme caution was needed to protect both teachers and students.

“I appreciate all the Monday morning quarterbacking here today, but we don’t need … data to tell us that if kids are not in school they won’t learn,” said Connecticut Democrat Jahana Hayes, the 2016 National Teacher of the Year. “We also know if kids are dead, they don’t learn.”

Nat Malkus, deputy director of education policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, countered by offering up data showing that schools overall proved not to be COVID “superspreaders” and that rates of death among children were less than 1%.

While it all sounds familiar, the debate offers a likely preview of the coming standoff over federal funding for 2024 — and a glimpse into the contentious role the education system’s response to the pandemic will play in the election season ahead.

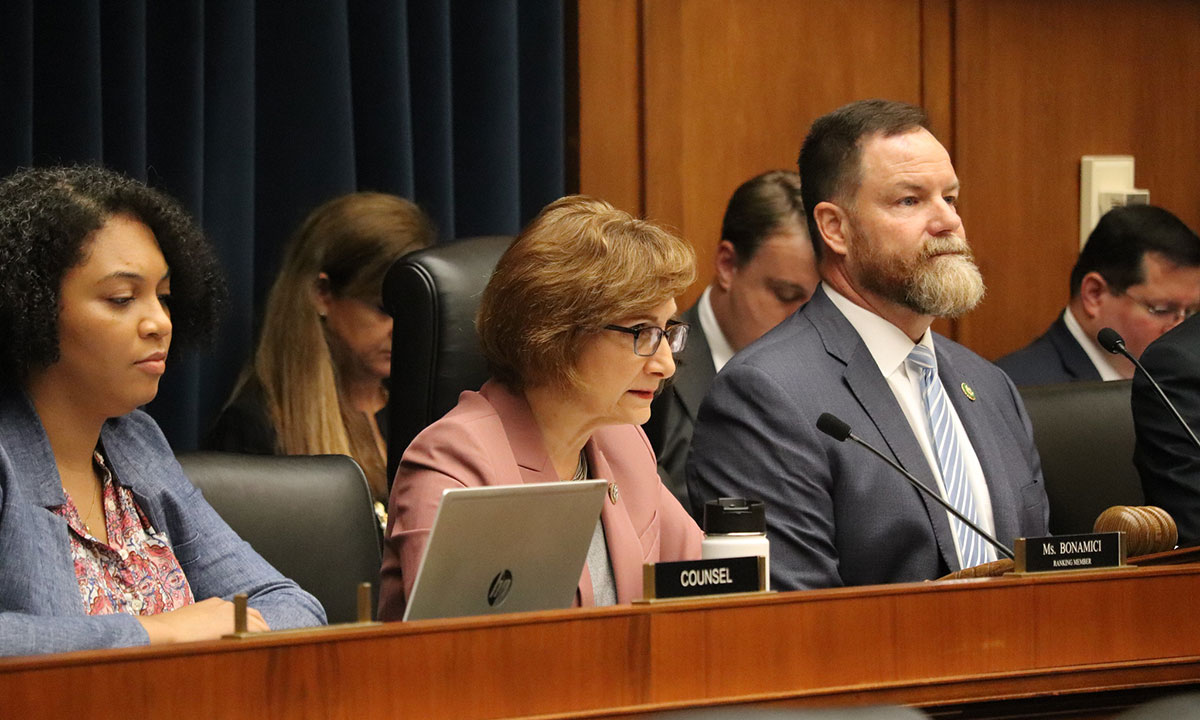

The House has proposed a $67 million cut to the education budget, noting that some districts still have unspent relief money and that parents would be better off using the funds for school choice. But Democrats, including Suzanne Bonamici of Oregon, ranking member on the subcommittee, said Republicans are obsessed with “extremist” culture wars and can’t be serious about learning loss if they’re willing to cut Title I funds for high-poverty schools and eliminate funding for teacher training.

Injecting her own Alanis Morissette title into the record, Mary-Patricia Wray, a Louisiana parent and witness for the Democrats, asked: “Isn’t it ironic that this Congress allocated funding for those programs, recognizing that they were needed, and is now about to take them away at a time when they’re also screaming loudly about learning loss?”

The founder of Top Drawer Strategies, a government relations and political consulting firm, Wray, who previously worked for the Louisiana Federation of Teachers, said it was “intellectually dishonest” for Republicans not to acknowledge achievement gaps that existed before the pandemic.

Score gaps between Black and white students and Hispanic and white students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress were beginning to narrow before the pandemic, data shows. Malkus stressed that closures stretching into the spring of 2021 only made those gaps worse and caused the “largest negative shock to student learning ever in the U.S.”

‘An eye-opener’

While union leaders weren’t called as witnesses Wednesday, the hearing came less than a week after American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten spelled out her vision for pandemic recovery, offering talking points and a roadmap for next year’s elections.

“Ninety percent of parents send their children to public schools,” she said. “Most parents trust teachers, and they want public schools strengthened, not privatized.”

She announced partnerships with literacy organizations to focus on reading and a $5 million campaign to promote community schools, mental health services and other efforts to support students. She blamed social media and “culture warriors who censor honest history” for holding students back.

The AFT, she said, offered a reopening plan in April 2020, but some critics still point to the slow pace of reopening in cities with strong unions, like Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington.

“The unions are surely hurting from being blamed — with some justice — for learning loss,” said Chester Finn, senior fellow and president emeritus at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank. “Randi is very smart.”

The hearing was a departure from issues Republicans have focused on since taking the majority in the House. In April, they passed legislation to bar transgender athletes from competing in women’s sports, and in March, they passed a bill that seeks to increase transparency into books and curriculum in schools.

The [Republicans] are all over the woke stuff, of course.” said Sandy Kress, a Texas attorney and education consultant who served in the second Bush administration. But he added, “the studies that showed we lost more ground after that unprecedented slug of money — they’re an eye-opener.”

North Carolina state Superintendent Catherine Truitt, who took office in 2021, joined the witness panel to describe her state’s efforts to help educators use the money wisely, especially those in small and rural districts.

She opened an Office of Learning Recovery and Acceleration to track student data and advise districts on how to spend relief funds. Leaders, she said, have spent some on summer “bridge” programs to prepare students for the next grade, math boot camps for middle school students and training on phonics-based instruction.

“That’s what we sent that money to you in order to do,” Hayes said, “for you to make decisions on the ground that would best support your students and your community,”

But questions over whether districts have used the money effectively are likely to continue, said Liz Cohen, policy director at FutureEd, a think tank at Georgetown University.

“If I’m in a district, and I have something that I think is working for kids,” she said, “I would be smart to get as much data as I can for the next six months.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)