In the ‘Crosshairs’: Beleaguered School Superintendents Face COVID Wave of Firings

Increased terminations reflect a more toxic brand of school politics. ‘The role of the superintendent has become a punching bag,’ one leader said

By Linda Jacobson | October 25, 2022Just months after COVID closed schools nationwide, Carlee Simon took over the Alachua County Public Schools with a plan to close the yawning gap in reading scores between Black and white students. At close to 50%, it was the largest in Florida.

But 15 months later, the superintendent in Gainesville was very publicly fired after the district defied Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis’s ban on school mask mandates. DeSantis appointed a board member who tipped the majority 3-2 against her. She was the district’s sixth leader in close to a decade.

“My district will have a hard time explaining the turnover rate of superintendents and convincing the right person to pull up roots and move to our community,” she said. “The governor’s culture war has impacted the work environment so negatively that a school superintendent would be working to push back a very strong current of low morale.”

Far from being an isolated incident, her termination is part of a COVID wave of superintendent firings from the Pacific Northwest to rural North Carolina. The charged atmosphere is a sign of the times, as toxic national and state politics filter down to local school districts.

A recent poll showed a clear decline in parents’ opinions toward their local schools. Those on both sides of the culture war have turned out in force at school board meetings — sometimes calling for superintendents to be fired or step down. But the issues have not been limited to closed schools or classroom controversies. Even run-of-the-mill decisions, like renovating buildings or replacing staff, have toppled careers. With alarming national test scores released Monday and pandemic relief funds running out in two years, the temperature is only likely to increase.

“We’re about to hit a different level of vitriol,” said Julia Rafal-Baer, co-founder of ILO Group, a consulting firm that helps future district chiefs find jobs. “We’re asking our leaders to be a sponge for divisiveness.”

‘Taking a risk’

The job of leading school systems has always been tricky. As they navigate complex bureaucracies and clashing constituencies from parents to teachers unions, superintendents are paid well (average salaries are in the six figures) but frequently burn out.

What’s changing, according to Jeffrey Henig, a professor of political science and education at Teachers College, Columbia University, is that now “we’re seeing a whole range of issues migrate into districts that in the past were somewhat buffered.”

Recent studies and surveys point to a general increase in superintendent turnover, but none has directly examined the spike in terminations. In conversations with district leaders and their advocates, however, many say the phenomenon is inescapable.

Kevin Brown, executive director of the 3,800-member Texas Association of School Administrators, said in his 31 years in the profession, he’s never seen more superintendents fired than he has in the past two years. And Steve McCammon, executive director of the National Superintendents Roundtable, a 100-member network, said it’s becoming common for members to be fired “without cause” — legal language that allows school boards to part ways with their chief executives without offering a reason, a hearing or other elements of due process. Previously, he recalled only one instance in the past 20 years.

“The stories are out there all over the place,” he said. “Everything has become a political decision.”

To get a sense of the scope of the issue, The 74 reviewed news clips detailing nearly 40 no-cause firings or forced resignations in 26 states since the beginning of the pandemic. The 74 also sent an informal survey to leadership networks, including the National Superintendents Roundtable, the Council of Great City Schools, Chiefs for Change, ILO Group and Education Counsel, another consulting organization. Out of 70 superintendents who responded, 15 said they’ve seen several district leaders fired or forced to resign since the pandemic began. Twenty said there have been many more. Nineteen worry they might be next.

“The role of the superintendent has become a punching bag … during the pandemic and the attacks are personal,” one wrote.

Another said: “I have board members running to remove me, and I run a very strong and high-performing school district. It is a dark and sad time for superintendents.”

As in Alachua, debates over polarizing issues preceded firings in dozens of school systems across the country.

Snapshot

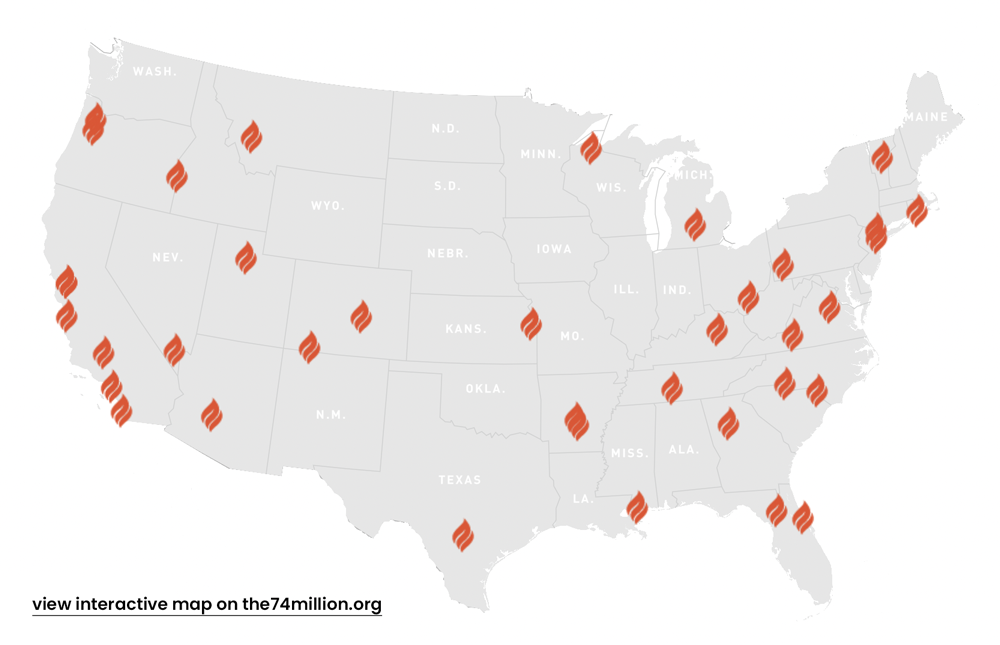

A COVID Wave of Fired Superintendents

When school boards fire their leaders, it is seldom done with transparency. Payouts to superintendents and non-disclosure agreements typically mean the public doesn’t get the full story. The map reflects a sample of school superintendents fired — primarily without cause — since the start of the pandemic.

When conservatives took over the board in Spotsylvania, Virginia, last January, they fired Superintendent Scott Baker, who was set to step down just five months later. The district was embroiled in debates over books with LGBTQ themes, with some board members calling for not only banning, but burning, library books they deemed “sexually explicit.” After banning several books, the district changed course after a public outcry.

In 2021, Kevin Purnell of Oregon’s Adrian School District was among a handful of leaders fired for simply complying with the law — in this case, a state mandate that students wear masks. The terminations prompted lawmakers to pass legislation this year that protects superintendents from being removed for following laws.

The perception that schools prolonged closures to protect teachers rather than serve students fueled a huge backlash from parents. Dozens of parents’ rights groups have sprung up since 2020, and Republicans have seized on the issue as a critical plank for upcoming midterm elections.

“School leadership failed students and catered to union agendas during the pandemic,” said Sharon McKeeman, founder of Let Them Breathe, which sued unsuccessfully over California’s mask mandate. McKeeman, who’s also running for school board in the Carlsbad Unified district, told The 74 that “it’s time for leadership that will put students’ needs first and help them recoup the learning loss and social-emotional damage they incurred during school closures and COVID restrictions.”

Part of the problem in tracking the issue is that such firings are typically shrouded in secrecy. For The 74, Rafal-Baer of ILO Group analyzed the departures of 210 chiefs who vacated their positions in the nation’s 500 largest districts since March 2020. Of those, 11 were fired. But based on news coverage, she suspects many more were forced to resign. Superintendents fired without cause often walk away with large buyouts and agreements for everyone involved not to discuss the terms.

“We never hear the real story,” she said. “They legally can’t talk.”

Issues over district management

But Cheryl Watson-Harris, fired in April from her post as superintendent of the DeKalb County schools in metro Atlanta, refused to go quietly.

Her termination capped off a two-week media storm following the posting of a viral video that exposed mold, crumbling ceilings and other safety hazards at the district’s oldest school. High school students shot the video after the board voted not to renovate the facility — an action she opposed.

Even before she walked into the job, Watson-Harris knew the district had a reputation for turmoil. Before they hired her, board members named former New York City schools Chancellor Rudy Crew as the sole finalist for the job, only to vote against hiring him two weeks later. He sued for discrimination based on age and race, and the board later paid out a $750,000 settlement. Rafal-Baer of ILO Group said she even advised another candidate not to pursue the position.

Nonetheless, Watson-Harris, who previously served as second-in-charge under former New York City Chancellor Richard Carranza, hoped her status as an outsider would help her rise above the district’s troubled politics. It didn’t take long for controversy to find her.

She proposed a reorganization that would require top deputies to reapply for their jobs in an effort to address what she felt was a lack of accountability over school improvement. She fired the district’s chief operating officer last year, according to local news reports, after an investigation found he bullied other employees and drank too much alcohol at a work conference. He sued the district, arguing that he was falsely accused of “a handful of minor violations” and that she retaliated against him for raising questions about accounting irregularities.

In an interview, Watson-Harris acknowledged “spotty recordkeeping” in the district, one reason she brought in outside evaluators to review finances and was upgrading outdated systems for managing staff and operations.

The former employee died in a car accident in September near Detroit, according to police reports. His attorney declined to comment on the status of his lawsuit.

Board Chair Vickie Turner declined to answer questions about Watson-Harris’s termination. The other three board members who voted to fire her, along with the school district’s attorney, did not respond to requests for comment.

“When you’re dealing with personnel matters such as this, you have to be very, very careful,” Turner said. “I don’t think it would be wise to speak to that, because we may have some things that are still not closed.”

Watson-Harris’s firing shocked many in the community, even drawing a rebuke from Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, who said the board chose “politics over students, families and educators.”

With just a month left in the school year, the board spent $25,000 to reprint diplomas without her signature.

“I could have closed out [the school year] and given people some stability,” Watson-Harris said.

Because she was fired without cause, Watson-Harris believes she was denied a chance to respond to the accusations against her. For that reason, she said, she’s refused to accept a $325,000 severance package and is considering legal action.

After watching the district go through four leaders in three years, state Superintendent Richard Woods finds the volatility troubling.

“You cannot get any continuity of services and support,” he told The 74, adding that consistent leadership is needed to “have some forward growth.”

‘In the spotlight’

Such churn is becoming commonplace. In her review of the nation’s 500 largest school districts, Rafal-Baer found more than 20 have had two leadership changes since COVID’s arrival.

Watson-Harris was both hired and fired during the pandemic. So was Florida’s Simon, who said she faced similar resistance from a board reluctant to challenge the status quo.

Alachua board member Tina Certain, who voted against Simon’s termination, said the former superintendent’s replacement of well-liked administrators and creation of a teacher advisory committee that included non-union members likely contributed to discontent.

“Every department I looked at had financial efficiency issues and basic management concerns — lots of ‘this is how we do things around here’ excuses,” Simon said.

That issue came to the fore when she raised questions about the financial management of a district-owned camp that runs outdoor education programs. She found that scholarships meant for poor students were being awarded to those without financial need, including the child of a former superintendent on a six-figure salary. She produced — and shared with The 74 — a text message between the camp’s director and a former staff member about scholarships given as a “thank you for being business partners.”

An internal investigation cleared the director of wrongdoing, but the district continues to push for tighter oversight of the camp. The director filed a defamation lawsuit against Simon, the district and the former camp staffer. He denied the allegations and said he didn’t violate policies because there weren’t any in place. His attorney didn’t respond to requests for comment.

But for DeSantis, it would appear that Simon’s vocal opposition to his COVID policies was the tipping point. “She went on the national news and put us in the spotlight in a very negative way,” Mildred Russell, the DeSantis appointee who cast the deciding vote to fire Simon, told The 74.

Simon now leads an organization that backs board members and superintendents who push for equity and inclusion. She doubts she could find another superintendent job in the state.

“I think every board in K-12 or higher education would be taking a risk of being in DeSantis’s crosshairs in the event they consider my employment,” she said. “We are asking for people to risk financial and professional stability.”

The governor’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

DeSantis — who is setting the GOP’s agenda on education policy and is widely seen as a potential 2024 presidential contender — expanded his reach into nonpartisan school board elections this year, endorsing 30 candidates in 18 districts. The majority won their races or have moved to a November runoff. Several of the governor’s candidates were also backed by the conservative organization Moms for Liberty, a parents’ rights group, and the 1776 Project PAC, which has spent over $2 million on school board races in several states.

The charged atmosphere nationally is producing leadership candidates who aren’t seasoned or politically astute enough to withstand the pressure, said Daniel Domenech, executive director of AASA, the School Superintendents Association.

“There’s no time to learn,” he said. “You’re going into battle now.”

That’s why Alachua is holding off on looking for a new superintendent, said Certain, the board member.

“We’re not going to get anybody who is worth anything at this point because of the turnover,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter