‘In the Crosshairs’: As School Closures Extend, States Face Complex — and Often Localized — Decisions About How to Help Seniors Graduate

As it becomes increasingly likely that schools nationwide will not reopen this school year in response to the coronavirus, more than two-thirds of states have started sharing game plans to get high school seniors their long-awaited diplomas.

In some of the most recent guidance out of New York state, home to the nation’s largest school district, the storied 144-year-old Regents exams in June are canceled following rising calls from advocates, educators and students to table them. To graduate, seniors typically need to have passed five of them during their high school career.

There was already discussion in New York state about abolishing the Regents, a reflection that setting high school graduation requirements in normal times is a debated and difficult proposition. Districts and states have to balance a want for the requirements to be rigorous enough to be a meaningful indicator of college and career readiness with the recognition that they can’t be so restrictive as to deny students, many of them the most marginalized, a key credential for a successful future.

The coronavirus has complicated, if not dismantled, that balancing act. Twenty-one states as of Saturday are already closed for the remainder of the school year, according to Education Week. New York state has not yet joined that group, though New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio on Saturday announced the closure of his school system, which serves 1.1 million students. Gov. Andrew Cuomo later said that decision belonged to him.

Even among states that haven’t yet closed through June, the new focus is to remove barriers created by digital divides and a pandemic beyond anyone’s control, and getting seniors — those on the cusp of meeting requirements, especially — graduated.

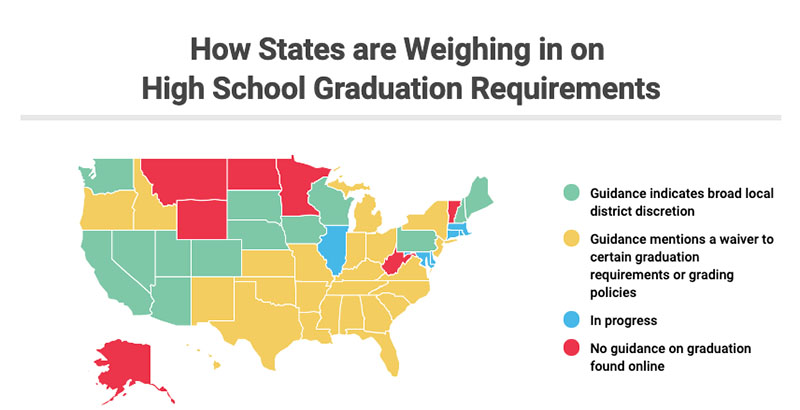

An analysis by The 74 found that at least 37 state education departments or boards of education had issued public guidance on their graduation criteria as of April 13, albeit with varying degrees of depth and completeness. About 25 of them have altered certain diploma requirements and policies for seniors, waiving exit exams or scrapping mandated credit hours and civics courses, for example. Others have kept them intact, giving districts outsize flexibility to design local plans to meet them.

Three additional states, including Minnesota, which had no guidance posted online, told The 74 over email that state directives aren’t needed, as each district “has created their own distance learning plan.” At least six more, including Rhode Island and Massachusetts, say they’re working on it. A few, such as Vermont, remain unclear.

The variance marks a departure from higher education, where more than 150 colleges have reverted to pass/fail grading. It’s symptomatic of the fact that there’s no go-to solution for retooling graduation requirements amid an unprecedented pandemic, pundit Rick Hess told The 74.

“Who the hell knows what the right answer is?” said Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

As Alliance for Excellent Education’s Anne Hyslop pointed out, there’s also the caveat that “graduation requirements were already localized in most states.” Local districts often tack on additional requirements to what the state mandates, handicapping states’ ability to easily enact sweeping changes. And while all but three states as of last year have a standard high school diploma, 29 offer more than one diploma option. Fourteen have at least three. All of these factors could postpone the dissemination of meaningful guidance, said Hyslop, the organization’s assistant director of policy development and government relations.

State directives or not, one common thread has emerged: School districts are ultimately being tapped as the final decision makers of what counts as a student meeting state requirements in a remote setting — adding to the already overflowing plates of local leaders and teachers.

While many superintendents could benefit from more fleshed-out state guidance, they’re stepping up, said Daniel Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators. Some are wary, though, of making their own decisions now only to later have the state change direction.

“I think superintendents do feel ready to make that call” on graduation requirements, he said. “The only trepidation that superintendents have is if the state is then going to come out and do something that is counter to the call that they just made.”

Some states have made concrete changes, temporarily gutting certain base diploma requirements to support seniors, especially those who were relying on this semester to make up credits and exams before schools shuttered. Among the 11 states that mandate exit exams to graduate (New York state falls under this umbrella), 10, including Texas and New Jersey, have suspended them, with Maryland considering waivers.

Students “[are] currently navigating unprecedented disruptions to their education,” Advocates for Children of New York wrote in an April 7 statement applauding New York’s decision to forgo the Regents exams. Students are still expected to complete required course credits. “It will be critical … that schools have the resources to provide young people with the additional academic and other support they will need to leave high school prepared for college and careers.”

In Arkansas, seniors this spring won’t be faulted if they haven’t completed civics, CPR and personal finance. Mississippi, like other states, is ditching its 140 instructional hours for each unit of credit. Idaho’s seniors no longer have to submit a senior project.

On the other side of the spectrum, Iowa directs districts to “provide as much latitude for students to graduate on time as possible.” In Maine, public guidance set in a blue box on the education department website reads, “WE SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL DECISIONS! … We honor the professionalism and judgment of the local [district] and school board to approve plans regarding continuity of education, graduation, and school days and will not require any additional documentation.”

The two states with the second- and third-largest school districts in the U.S. — California and Illinois — have begun to weigh in too. Illinois’s guidance is in progress but will hinge on local flexibility; California is keeping its minimum state graduation requirements but says a district can modify any additional standards it has implemented. Districts can request requirement waivers for specific students.

Hess typically touts local empowerment in decision-making. But he worries that too much flexibility in this case could put thousands of districts nationwide “in the crosshairs,” poised to be blamed by the community and parents for making an unfavorable decision.

“I think it makes a lot of sense for folks at the state level to lay out, ‘Hey, there’s no perfect choice. We’re weighing the upsides and downsides. Here’s what we think works for our states,'” he said. “And then give local officials as much leeway and flexibility as they can to serve kids within that framework.”

A group of states appear to be pursuing a sort of happy medium: local decisions, but explicit guidance on what the state thinks could be done.

In Virginia, a bulleted memo outlines where local superintendents have been granted authority to waive certain mandates, like a career and technical education credential. Kansas is reminding districts that the state’s minimum diploma requirements are 21 credits and that they can scale back on add-ons, like internships and community service hours. Washington state, which Hyslop considers some of the best guidance given so far, reviews five different options districts could use to meet credit requirements, from project-based learning to using “pass” or “no credit” designations instead of letter grades.

At least seven states, including North Carolina and Ohio, have also advised districts to consider students who were on track to graduate when schools closed as having met the bar for graduation. North Carolina seniors passing their courses as of March 13 will get a designation saying so — one that won’t have any bearing on their grade point average. Domenech said many superintendents he’s spoken with intend to take a similar approach, considering “the huge discrepancy across districts to offer online instruction” in past weeks.

That doesn’t mean districts should discount a student who was falling behind before the school closures “but has done everything that they can to improve” since then, he noted. States are expressly asking schools and districts to make every effort to offer alternative opportunities for seniors at risk of not graduating to prove their understanding of course material and to provide summer work and credit recovery if needed.

South Carolina, in a seemingly unique move, is holding a virtual “special enrollment” class for seniors who need to take economics. It’s running from April 6 to April 30. Alabama is reminding districts to “continue to find methods to support seniors’ next steps,” too, “such as assisting with FAFSA, scholarship applications, applications for post-secondary opportunities, etc.”

Some universities have implemented their own measures to alleviate student stress, especially around testing. At least 17 colleges have dropped the SAT or ACT for one to two admissions cycles because of the coronavirus. A few, like Boston University and Tufts University, are going test-optional. The University of California system has also temporarily suspended the requirement that admitted 12th-graders earn at least a C in senior-year classes in “A-G courses,” which include English, math and science.

While all of these accommodations at both the high school and college levels have been made temporarily, Hess believes it will force an introspective look at the education system — at what’s truly the best way to teach students.

“What we’re [now] being rudely pushed to remember when it comes to grades, when it comes to graduation requirements, is that we don’t actually know that these things make sense,” Hess said. “I think a bunch of questions will come up: Does it actually matter for college success if kids finish senior year or not? Are there courses where kids’ learning seems to be deeply impacted by losing three months of school — and where it seems to not be impacted at all?”

It’s only the beginning of the conversation. Additional state guidance is expected in the coming weeks, Hyslop said — especially as more and more states formally close for the rest of the school year.

Going forward, she said, she hopes to see guidance updates offered more readily, even if they’re incomplete, and in a way that’s free of jargon and speaks plainly to parents.

“Your average parent isn’t likely going to the state education website to figure out what’s going on,” she said. “They need to be hearing this information directly from their school or from the district.”

“Guidance,” she added, “is only as useful as it can be accessed and understood.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)