In 2022 Midterms, Career Ed Emerged as Rare Source of Bipartisan Agreement

New analysis of governors’ races in 2022 finds that Democrats, Republicans saw eye to eye on little except expanding CTE and raising K-12 funding

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In 2022, 36 states elected governors, and the races saw clear partisan divides on education topics from school safety to teacher pay. But a new analysis suggests that the 72 Democrats and Republicans running to lead their states found a few select issues they could all agree upon.

Foremost among them: expanding career and technical education.

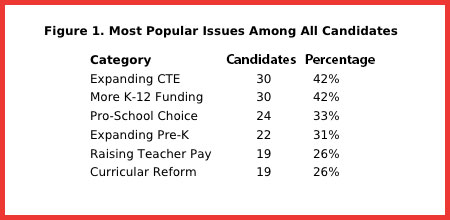

Andy Smarick, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, scoured the websites of all 72 major-party candidates in 2022’s gubernatorial races. In all, he found 27 education issues supported by at least one candidate.

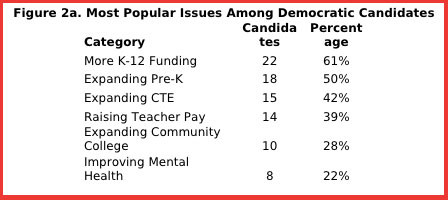

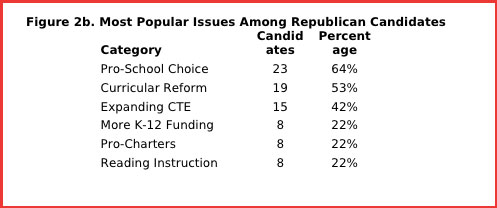

The data suggest clear partisan divides: Among Democrats, the top two issues mentioned were increasing K-12 funding and expanding Pre-K. Among Republicans, it was school choice and curricular reform.

But one issue rounded out the top three among both Democrats and Republicans: CTE. Along with greater funding, it was mentioned more frequently than any other topic. In all, 30 candidates, or 42%, featured it on their websites.

Higher funding held a distant fourth place for Republicans, far below CTE. An equal percentage of GOP candidates — 22% — expressed support for charter schools and better reading instruction.

Smarick, a member of the University of Maryland System’s Board of Regents who has also served as chair of the state’s Higher Education Commission and president of its State Board of Education, said he wasn’t surprised to find CTE hold such a prominent place.

“So many people have pushed for so long for a ‘college for all’ mentality, which was good and important, that now a lot of elected officials are saying we also have to do something on certificates and certifications and apprenticeships” and other career-driven outcomes.

He also noted that many college-going students don’t end up with a four-year degree. “So state legislators and governors have to think in terms of ‘How do we serve all of these adults?’”

The findings resonate with those of a survey released earlier this month that found Americans now want K-12 education to focus on “practical, tangible skills” such as managing one’s personal finances, preparing meals and making appointments. Such outcomes now rank as Americans’ No. 1 educational priority.

U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona is already signaling that CTE is a priority: Last week he previewed the administration’s “Raise the Bar: Unlocking Career Success” initiative, which seeks to overhaul secondary education with an eye toward granting students the skills and credentials necessary to enter college or the workforce after 12th grade.

Designed in concert with First Lady Jill Biden as well as the secretaries of commerce and labor, it urges colleges to offer dual-enrollment coursework to high school juniors.

The National Student Clearinghouse has estimated that the number of students with “some college, no credential” in 2020 grew to 39 million, roughly the population of California.

It may be a surprise, then, that while 28% of Democratic candidates in Smarick’s analysis mentioned expanding community college, not a single Republican did.

Big differences between incumbents, challengers

Smarick also broke out mentions between incumbents and challengers, finding that non-incumbent Democrats discussed several issues that no incumbent did: One in four articulated what he called an “anti-school choice position,” and more than one in five argued for less school testing.

He theorized that perhaps these challengers “believed taking these positions would help them win primaries and garner support of teachers’ unions.”

Likewise, 38% of Republican non-incumbents expressed support for charter schools, while not a single Republican incumbent did. Non-incumbents were about twice as likely as incumbents to say they supported school choice more generally (81% to 40%). Smarick suggested that this is because these non-incumbents, like their Democratic counterparts, were also focused on winning primaries and earning the support of base voters who support more ideological causes.

Incumbents, he said, zeroed in on more practical day-to-day issues like early childhood and funding and, in red states, expanding the number of choices available to families. “It just seems like once you’ve been in office for a while, a lot of these incumbents realize that lots of families like their traditional public schools and they want to make sure that they’re well-funded.”

That may especially be true of schools in the “COVID era,” he said, which need extra funding so students can recover academically.

More broadly, Smarick said, public opinion polls consistently show that the public “likes the idea of well-funded schools. So it’s not really a surprise that incumbents, including Republicans, put that on their list of things that they want to make sure they accomplish.”

Harvard University education scholar Martin West, a co-author of the annual Education Next public opinion survey on school issues, said the differences between incumbents and non-incumbents are “fascinating” and suggest that “the experience of running a state school system, or perhaps the responsibility of having run one, has a moderating effect on candidates’ views.”

He also noted that the striking differences in positions taken by Democrat and Republican candidates are consistent with the most recent EdNext findings showing greater partisan polarization overall.

Blue state, red state, swing state divides

When it came to the states candidates were vying to lead, Democratic nominees didn’t offer many surprises: Those in blue states supported traditional “higher-dollar” initiatives such as expanding pre-K and community college, and raising K-12 funding levels and teacher pay. And while blue-state Democrats talked about investments in community college and university systems, swing-state Democrats were much more likely to discuss CTE.

As for Republicans, red-state GOP candidates were actually less likely to advocate for more red-meat Republican positions such as a parents’ bill of rights or measures to block so-called critical race theory in the classroom. Just one in five GOP nominees in red states advocated for these policies, fewer than in blue or swing states.

Perhaps most striking: In blue states, more than half of GOP nominees took a pro-charter position, but in red states, not a single GOP nominee did. They were also four times more likely to advocate for more K-12 funding than their blue-state GOP counterparts.

Smarick said that perhaps red-state GOP nominees saw less of a need than their blue-state counterparts to fret about instructional crises in schools — or that perhaps their states’ public schools perform well enough to lessen the need to advocate for school-choice and charter reforms.

But it may also suggest a kind of “remarkable” generational change around charter schools, he said.

“If we go back 10, 15, 20 years ago, lots of Republican candidates were more willing to talk about charter schools than school choice,” Smarick said. “Now it seems to have flipped.”

And since many of those pro-school-choice Republicans won their races, he said, “in red states, we’re going to see the tax credits, more ESA [Education Savings Account] stuff. And this is different than it was, certainly, a generation ago.”

Overall, nearly two-thirds (64%) of Republicans in Smarick’s analysis talked about supporting school choice, while just one Democrat, Pennsylvania’s Josh Shapiro, mentioned it.

When it came to how these issues played out, Smarick found a few surprises: Increasing K-12 funding was a “top-five” issue among winners in blue, swing, and red states.

Matt Hogan, a partner at the Democratic polling firm Impact Research, said he wasn’t surprised. He said Impact’s polling has consistently shown that increasing K-12 funding “is very popular and its continued popularity is consistent with voters’ desire a focus on bread-and-butter issues when it comes to education, rather than engaging in culture war fights.”

For Democrats, Harvard’s West noted, the push for more K-12 funding was paired with expanding Pre-K and community college, two investments “with which K-12 funding will have to compete.” That may help to explain why states that switch from Republican to Democratic control have traditionally spent a bit less on K-12 schools, he said.

In the end, what might be most significant in Smarick’s findings is what’s not mentioned: teacher shortages. They got “minimal attention” from candidates, with just three of 72 even mentioning the issue.

“I kept looking through these websites, expecting half or three-quarters of candidates to talk about it, and they just didn’t,” Smarick said.

Though the issue was all over the news in 2022, “It was the dog that didn’t bark” on candidates’ websites. “Which makes you think maybe we ought to take a look at what’s happening in states as opposed to just following national narratives about education policy.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)