Immigrant Advocates Call on Massachusetts AG to Probe Enrollment Discrimination

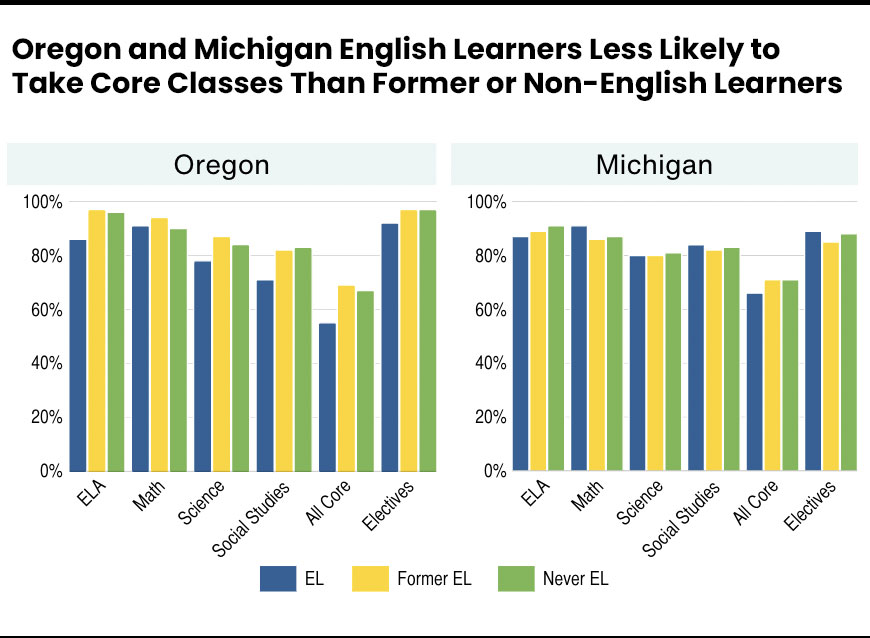

Researchers looking at two other states — Oregon and Michigan — find English learners less likely to take essential core classes than their peers.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, Sept. 23

Lawyers for Civil Rights and Massachusetts Advocates for Children filed a lawsuit Sept. 18 against Saugus Public Schools seeking the release of records around the district’s admissions policy. The legal advocates claim the policy, which mandates that families fill out the town census among other requirements, disproportionately affects immigrant and other vulnerable student groups. Saugus district officials did not respond to a request for comment.

Just weeks after Massachusetts attorneys flagged two school districts for allegedly denying newcomer students their legal right to an education, researchers examining Oregon and Michigan state data found that English learners were less likely than other students to be enrolled in the core classes they need to graduate.

Both of these issues were called out in a June undercover investigation by The 74 that revealed rampant enrollment discrimination against older immigrant students. These newer findings show many such barriers remain in various parts of the country.

Boston-based Lawyers for Civil Rights and Massachusetts Advocates for Children asked the state attorney general’s office on Aug. 28 to investigate Saugus Public Schools for practices they say single out immigrant children: The school system currently bars entry to students whose families did not complete the annual town census.

While local census data collection is mandatory in Massachusetts, lawyers say it can’t be tied to student enrollment.

“With school starting in Saugus this week and the School Committee digging in its heels, it is imperative that the Attorney General intervene,” Erika Richmond Walton, an attorney with Lawyers for Civil Rights, said in a statement last week. “No child in Massachusetts should be denied the right to an education based on exclusionary policies.”

In an earlier interview, attorneys said that the district also applies overly-stringent residency and proof-of-identity requirements that make it difficult for children — especially immigrants — to register, violating their rights under federal and state law.

The attorney general’s office said in a statement that “it is in touch with the Saugus School District regarding their school admissions policy,” noting that “federal and state law gives all students equal access to a public education, regardless of immigration status.”

Saugus Public Schools, 11 miles north of Boston, served 2,462 students in 2023, up from 2,297 two years earlier. In the 2023-24 school year, English was not the first language of 31% of Saugus students and 13% of students were classified as English learners. The district was 29.6% Hispanic in the 2022-23 school year, slightly higher than the state at 24.2%.

The 74’s enrollment investigation also found that some school personnel who were willing to admit an older immigrant student wanted to severely limit his participation, including allowing him to take only ESL classes. Researchers in Oregon looked at the practice they call exclusionary tracking in their own state and Michigan.

Analyzing statewide data from the 2013-14 to 2018-19 school years, they found that just 55% of English learners in Oregon were enrolled in all the required core classes compared to 69% of those students who had graduated from the English learner program and 67% who were never enrolled in it.

In Michigan, 66% of English learners were enrolled in all of the core classes compared to 71% of former English learner students and those who were never enrolled in the program, according to the most recently available statewide data from the 2011-12 to 2014-15 school years. Under federal law, public schools must ensure that English learners can “participate meaningfully and equally in educational programs,” including having access to grade-level curricula so they can be promoted and graduate.

Researchers said race and socioeconomics were critical factors in exclusionary tracking, noting that English learners in Oregon were more likely to take standalone English language development classes and live in poverty than those in Michigan.

“The scope of the problem is pretty large,” said Ilana Umansky, an associate professor at the University of Oregon who co-wrote the report. “It’s so important that kids can get through high school and graduate with a regular diploma.”

Immigrant advocate Adam Strom called the actions in all three states an outrage.

”Exclusionary tracking and denial of registration for immigrant students not only violate their legal rights,” he said, “but also rob the entire school community of the rich cultural and intellectual contributions these students offer.”

Unwelcome to America

Senior reporter Jo Napolitano spent nearly a year and a half calling 630 high schools around the country trying to enroll a 19-year-old newcomer whose education had been interrupted after the ninth grade. Napolitano posed as the student’s aunt and told schools “Hector Guerrero” had recently arrived in their district from Venezuela with limited English skills.

Hector was turned away 330 times, including more than 200 denials in the 35 states and the District of Columbia where he had a legal right to attend based on his age.

Those who refused our test student predicted that he would not graduate, a factor that should not have played a part in such a decision, several state education department officials said. Thirteen states and three major cities have now said they are taking action to bolster newcomer students’ educational rights as a result of The 74’s reporting.

Three schools in Massachusetts, where students have a right to attend until age 21, denied our test student and two more said they were likely to. Education officials there told The 74 last month they would call those districts to discuss the findings, but planned no other statewide corrective measures.

Saugus schools Superintendent Michael Hashem’s secretary, Dianne Vargas, handles enrollment in the North Shore district. She told The 74 last week that its policies are lawful and that she’s in regular contact with the state education department and state attorney general’s office.

She maintained that the requirement that “(f)amilies who move to Saugus must complete the Town of Saugus census” to be eligible to register their children is waived for incoming immigrant students and that the rules were in place before August 2023, when the attorneys say they were adopted.

But, she said, the district does require other forms of paperwork — all meant to protect these students’ welfare.

“We want to make sure they are with a parent or guardian — that they actually have someone who is caring for them so we don’t have doubling up and people aren’t passing children around,” she said. “We have a good amount of scattered living or sheltered students who are refugees or migrants and they cannot be left without guardianship. We have a translator … we have everything up to date and make sure these people feel welcome.”

She said her office asks for — but does not require — a birth certificate and medical records. But Diana I. Santiago, a senior attorney and director at Massachusetts Advocates for Children, said Saugus’s enrollment policies effectively barred at least two immigrant families from enrolling their children in a timely manner, resulting in “substantial time” out of school.

The enrollment policy warns that parents, guardians or any others who “violate or assist in violation of this policy by submitting false documentation, aiding, abetting or conspiring to admit a child as a student of Saugus Public Schools, shall be subject to all applicable criminal and civil penalties.”

It also pledges that if a student’s family moves out of the district during the school year, that student’s “immigration records required by law, shall be transferred immediately to the school in the city or town where they are residing.”

It’s unclear why the district would be in possession of a student’s immigration records. Schools cannot, under federal law, turn away students based on their immigration status, although conservative forces are now looking to challenge those protections. At an Aug. 30 Moms for Liberty gathering, GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump said the country is “being poisoned” and that immigrant students are “going into the classrooms and taking disease, and they don’t even speak English.”

Closing doors

Santiago described the language used throughout Saugus’s enrollment policy — including terms like “legal residents” and “immigration paperwork” — as coded and meant to target the city’s growing immigrant community.

“It’s just inserted there as another way to try to keep students out, especially immigrant students,” she said.

Massachusetts is generally considered a national leader in education. The state attorney general’s current guidance to school districts on its website said it’s critical they “ensure that all children residing in their jurisdictions have equal access to public education” by allowing them to enroll and attend school without regard to race, national origin, or immigration or citizenship status. They must also avoid information requests “that have the purpose or effect of discouraging or denying access to school” based on those factors.

In another Bay State case that set off alarms in late July, Norfolk Town Administrator Justin Casanova-Davis said a change in the state’s emergency shelter system meant children temporarily housed at one location “will not be enrolled in Norfolk Public Schools or the King Philip Regional School District.” After pushback from immigrant advocates, he reversed the statement.

The 74’s investigation revealed a litany of ways that districts make enrollment arduous or unwelcoming for immigrant students. A principal in Green River, Wyoming, said our test student could be admitted but “wouldn’t get to participate in extracurriculars,” while a Caldwell, Idaho, principal said he would “maybe” allow him to enroll in math and science classes, but not English or history.

The Oregon researchers said the practice of keeping English learners out of core classes is significant and undermines Lau v. Nichols, a pivotal 1974 Supreme Court case that requires districts to meet their students’ language needs.

Umansky and co-author Karen D. Thompson, associate professor at Oregon State University, have spent years researching educational inequity for English learners.

Thompson said exclusionary tracking goes against high schools’ mission to graduate students college and career ready. Improved teacher training, added instructional time and an adequate number of school counselors, they said, can boost student access.

“We want students who are classified as English learners to be able to learn and thrive and have all of the opportunities they can,” she said. “If their access to core content is restricted, some future doors might be closed to them.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)