‘I Feel The Anger of 65 Years’: On Anniversary of Brown v. Board Ruling, NYC Panel Confronts Continued Segregation in Nation’s Largest School District

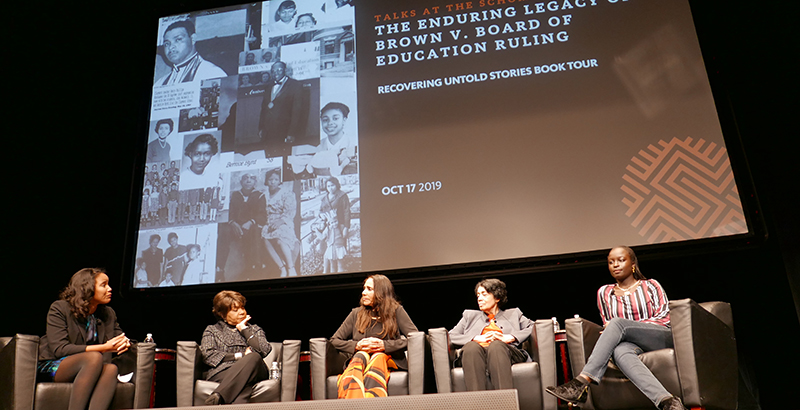

(From left) Moderator Cara McClellan and panelists Cheryl Brown Henderson, Brigitte Brown, Joan Anderson and high school senior Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye discuss the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City on Oct. 17. (Bob Gore/ The Schomburg Center)

New York City

Sitting next to three women whose families took enormous risk to help usher in school desegregation 65 years ago as part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, high school senior Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye’s outrage was palpable.

“We are another class of students who have been in and out of this system and still have been deprived of the education that we deserve,” the 18-year-old told a rapt audience at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. “I feel the anger of 65 years. I feel the anger of 250.”

The three women beside Ndiaye — Cheryl Brown Henderson, Brigitte Brown and Joan Anderson — had come to Harlem as part of a nationwide tour to share the unsung stories of plaintiffs in the pivotal 1954 Supreme Court case, which declared separate but equal schools unconstitutional. Yet right outside the center’s doors, New York City’s public schools, with its 1.1 million students, remain among the most segregated in the country.

Ndiaye said only “a handful of white students” have sat next to her in the 11 years she’s been a student in New York City schools. A leader in Teens Take Charge, a student activist group that’s spearheading a school integration campaign, Ndiaye joined the panel midway through to talk about the city’s continuing struggles with segregation, and the ways her generation is taking up the mantle.

The teens’ efforts embody a call to action that was as much a part of Thursday’s two-hour discussion as was the celebration of past civil rights battles. Panelists stressed the urgency of raising awareness about educational inequities for students of color — both in the time of Brown v. Board and today — along with the importance of valuing education and holding those in power accountable.

“It’s important for us to know this history so we can recognize the dynamic [of segregation] when we see it happening … so we can stop it,” said Henderson, the youngest daughter of Oliver Brown, the case’s namesake. “Vote, shout, show up, stand up and speak up.”

The panel, which drew about 100 attendees and was co-sponsored by The 74, kicked off with the women sharing their families’ often-overlooked contributions to Brown v. Board. The lawsuit is often misrepresented as Henderson’s father’s fight for an equal education for his oldest daughter, Linda, in 1950s Kansas. In actuality, Brown v. Board was five different cases that also encompassed families from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia and Washington, D.C. The cases were consolidated as the Supreme Court took up the issue of school segregation.

Brigitte Brown and Joan Anderson’s parents were plaintiffs in one of those cases: Belton (Bulah) v. Gebhart, brought by a group of African-American parents fed up with traveling 20 miles round trip to send their children to Howard High School — the only high school in Delaware that admitted black students — when the all-white Claymont High School was nearby. A judge ruled for the immediate integration of the plaintiff’s children at Claymont in 1952; the State Board of Education appealed the decision to the Supreme Court. (Read about the other cases here).

When Brown’s mother, Ethel, was a teenager, she would take an arduous hours-long commute on a city bus to Howard High each day, despite suffering from a heart condition. Located in the northern part of the state, the school was in “an industrial area” and flanked by old buildings, Brown said. It was filled with caring teachers who “stressed” education, but it was severely underfunded, with old hand-me-down books.

“If you were in lower Delaware … you did not go to high school once you passed eighth grade — period,” Brown said. “Unless you could find a way or live with some relatives or friends up north.”

Anderson’s experience was more direct — she was one of 11 children tied to the lawsuit who integrated Claymont High School in 1952 after the judge’s ruling. (Brown’s mother Ethel ended up moving, and was the one child in the case who didn’t end up attending Claymont). While there was widespread support at the school for integration, Anderson said navigating uncharted territory was still stressful.

“We were used as a test as to whether integration could work or not” before Brown v. Board, Anderson said. Outside of Claymont, “There was still segregation around us.”

Their families’ sacrifices “opened a door for many, many people,” Brown said. Nonetheless, she bemoaned how desegregation has “happened at a slow pace.” Brown saw the aftermath of “white flight” firsthand when she lived in the suburbs during her secondary school years in the late 1970s and was one of only about 30 students of color in a high school of 3,000.

“Sometimes I look at [the history of desegregation and think], did it really happen?” she said.

Addressing long-standing segregation in New York City’s public schools has taken on fresh urgency in the past two years, particularly in its eight specialized high schools. At one of them, the storied Stuyvesant High School, just seven seats out of some 900 went to black students in the fall 2019 freshman class. But a comprehensive solution continues to evade schools officials amid contentious disagreements citywide on how to create an equal education for all students. When Mayor Bill de Blasio last year introduced a plan to secure more spots for students of color at the specialized high schools, in part by eliminating the sole entrance exam, Asian-American families — whose children disproportionately make up about 60 percent of enrollment — sued for discrimination. A School Diversity Advisory Group proposal in August to phase out the system’s predominantly white and Asian gifted and talented programs also unleashed heated debate, and it has yet to garner explicit support from the city’s education department or mayor.

Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, who cited desegregation as a top priority when he assumed his role in April 2018, has yet to suggest a citywide integration plan of his own. He has, however, been a major proponent for culturally responsive education in schools —an approach that embraces curricula relevant to marginalized students’ experiences.

For now, school integration remains a grassroots effort in pockets of the city.

Carranza acknowledged last year that “64 years [after the Brown v. Board ruling], what do we, the collective we, have to show for that? I will tell you that in communities across America, the answer is, not much.”

The district’s failure to take immediate action is a slap in the face for students who have repeatedly demanded a better education, Ndiaye told the panel.

“I was told that things changed. Why do the adults keep on lying to me?” she asked. Ndiaye added: “I have a sister who’s going to be applying for the high school process, and I feel fear knowing that I am going to college and leaving her in a school system that I do not trust.”

Ndiaye was vague about Teens Take Charge’s agenda for this year, but she suggested the group would be upping the pressure on local officials. Last year, they staged a sit-in at City Hall, spoke before the New York City Council and demanded action from de Blasio on TV.

It’s students like Ndiaye who give the Brown v. Board generation hope, Henderson said.

“It was young people that brought us this far, so it’s good to see that this generation of young people recognize that,” she said. “We applaud you.”

“The squeaky wheel gets the attention,” Brown added. “And that’s what you have to do. Be the squeaky wheel.”

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation, a sponsor of the event, also provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)