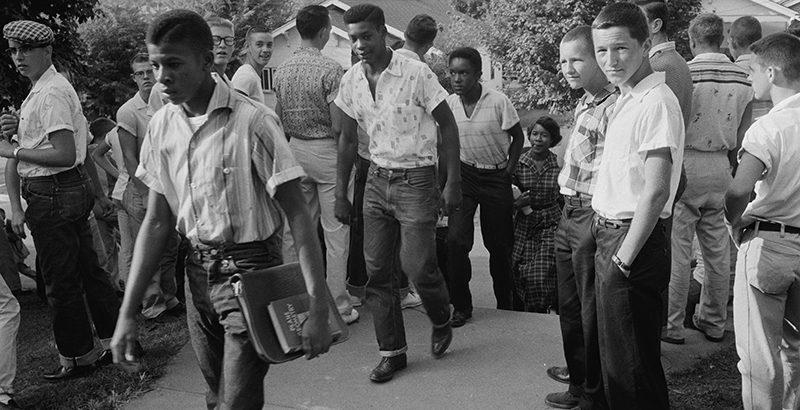

America’s Schools 65 Years After Brown v. Board: 7 Things to Know About the Unsung Plaintiffs Who Joined Forces to Reshape Education Six Decades Ago — and the Challenges That Remain

This autumn, The 74 is honored to be partnering with the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research, the Thurgood Marshall College Fund and the Walton Family Foundation in organizing a cross-country conversation series to commemorate the 65th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court verdict that established segregated schools as unconstitutional.

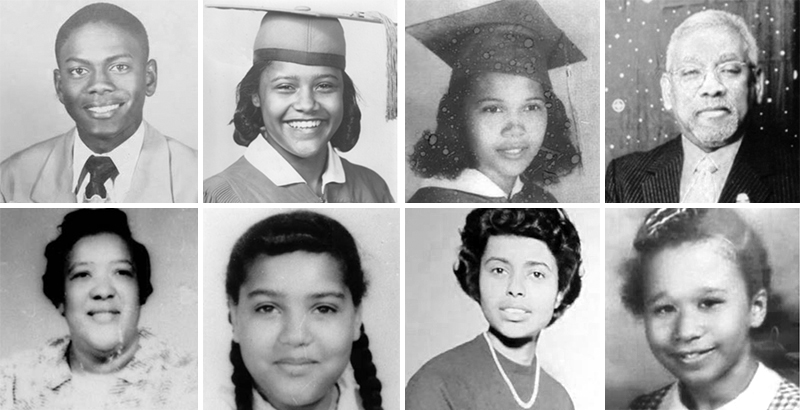

Through the coming months, we’ll be using this tour to spotlight and celebrate the many unsung plaintiffs who risked so much to file individual lawsuits half a century ago, eventually combining their cases into what became known as simply Oliver Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al.

Behind that first “et al.” is a lesser-known universe of harrowing true stories, featuring courageous parents, students and educators who deserve far greater recognition for all they risked and all they accomplished. We’ve set out to catalog the stories in a series of memoirs, many of them penned by relatives of the actual plaintiffs, at our special Brown v. Board microsite: The74Million.org/Brown65.

In advance of our first event in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 17 (you can get more info and RSVP right here), we’ve compiled a reading list for those looking to dig deeper — including a summary of the many court cases that merged together to form Brown, a video with Cheryl Brown Henderson on her father’s unlikely journey into history, a research roundup of how far schools have (and haven’t) come in achieving equity for all students, and a handful of essays that put into context this ongoing fight to close America’s startling achievement gap.

Here are seven things to know about Brown v. Board, and the arc of American schools in the 65 years since the Supreme Court spoke:

History: Most people know the story of Oliver Brown and Topeka, Kansas. But fewer know about the complex web of lawsuits and plaintiffs, spread out across five cities and states, that was strategically woven together to get school segregation on the docket of the U.S. Supreme Court. From South Carolina to Virginia, from the District of Columbia to Delaware, Cheryl Brown Henderson captures the stories and the characters behind the five pivotal lawsuits that were appealed, introducing the families who were willing to stand up for what was right and the courtroom machinations that eventually took Brown v. Board, et al. to the high court. Learn more about all five cases right here.

Brown v. Board at 65: Will Schools Ever Be Integrated?

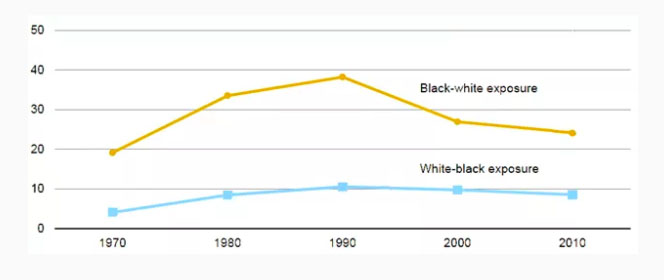

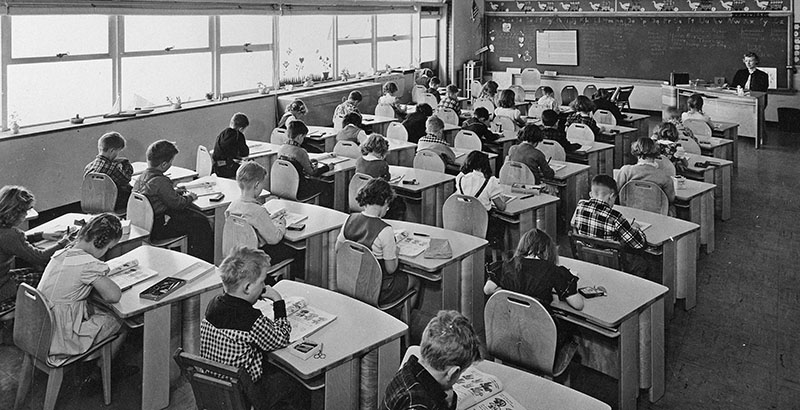

Research: Your neighborhood is getting more diverse, so why isn’t your school? Sixty-five years after Brown v. Board of Education, the United States is more integrated than at any time in its history. With urban cores rapidly gentrifying and the Latino population surging, American communities have become much less homogenous in recent decades. But for over a generation, black and white students have seen less and less of each other at school. With demographers pointing to a minority-majority future in just a few decades, educators are asking how to make schools look more like America. Some believe the answer lies in changing patterns of residential segregation, but others say the political will to bring together students of all races simply doesn’t exist. Read the full analysis.

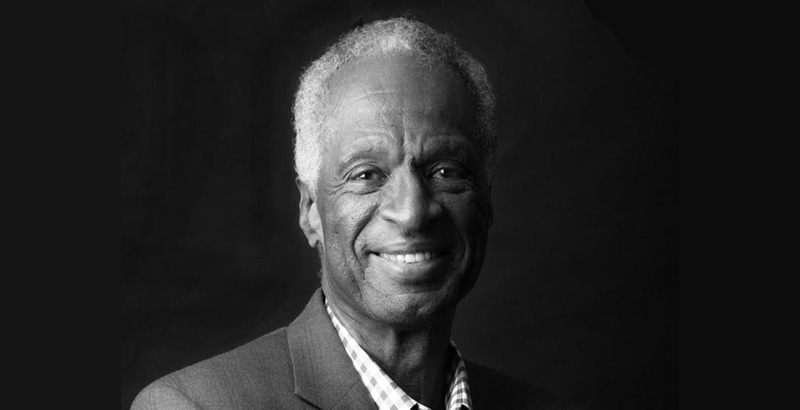

74 Interview: Veteran education reformer Howard Fuller was in eighth grade in 1954, when the Supreme Court reversed over a half-century of legal school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. Today, as an activist in his native Milwaukee, he works with kids who are about as old as he was then, trying to keep them on track for college and career. But he’s much less concerned with renewed talk of racial integration than with providing minority families with better educational options. Fuller is not much impressed with the current debate around race and education: the “young white people” who talk excitedly about putting school integration back on the agenda; the critics who say charter schools, like the one recently renamed for him in Milwaukee, contribute to segregation; or even Brown itself, which he says helped buttress the sentiment that predominantly black institutions were, by definition, inferior. Talking about integration, he told The 74: “Maybe, in certain communities, you might be able to pull it off. … But in the community that I live in, and for the kids that I’m trying to represent in our school, that discussion is irrelevant.” Read the full interview.

Commentary: After 65 years, maybe it’s time to stop waiting. Every few years, there is a predictable tide of articles proclaiming that our schools are still just as segregated as they were when the landmark Brown decision was decided in 1954. What you won’t find in any of these articles, writes contributor Chris Stewart, is much sober reckoning with the fact that integration was a colossal failure that in many instances produced more damage than progress. Says Stewart, “We lost so much by placing our faith in the social engineering of schools that robbed us of black educational capital and infrastructure. … Perhaps it’s time we believe in ourselves and reclaim responsibility for educating our children. One leap into that direction begins by admitting that Brown is not the big idea for ending the gap between black student underperformance and black educational excellence; it’s not the key to breaking the cycle of poverty for many black families; it’s not the key to making white people less racist, and it’s not a school reform that will restore the teaching and learning that existed before the illusion of integration wipe away our assets. … Yes, it’s been 65 years since the Brown decision promised integrated schools and better education. That’s too long for us to have ignored that the goal is quality schools however they may be composed.” Read the full essay.

Oral History: Cheryl Brown Henderson is one of the three children of the late Rev. Oliver L. Brown, namesake of Brown v. Board of Education. In this interview, Brown Henderson recounts her personal experience with segregated schools and the story of how Brown v. Board of Education came to be. She is founding president of The Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research, established in 1988, and owner of Brown & Associates, an educational consulting firm that she established in 1984. Watch the full video.

Analysis: More than half of American schoolchildren attend a school that is 75 percent white, or nonwhite, and many schools are more segregated now than before the Brown v. Board of Education decision 65 years ago. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, writes contributor Shavar Jeffries, given the widespread and long-standing resistance to integration efforts that didn’t end with the forced integration of schools in the South 15 years after the decision was handed down. That Brown, while achieving important results for meaningful numbers of children of all races, has not lived up to its promise is not the fault of Brown, or of the American heroes who litigated it; it’s the fault of underlying white supremacy that sadly continues to plague our nation, he says. “The educational inequities that continue to exist for black children are, plainly, symptoms of that underlying white supremacy that made Brown necessary in the first place. Until we engage in the hard, deep, painful and long-term work of fully healing our racial wounds, educational opportunity in our country will remain racially distributed. In the meantime, those of us committed to educational equity should be pragmatists and support (or oppose) policies based on their capacity to bring about educational equity for black children. Everything else is and should be secondary.” Read the full article.

Teacher’s Perspective: Though school desegregation became the law of the land in 1954, it would take years — and in some cases, decades — for local districts to adhere to the new national policy. That was the case when contributor Alicia Ramsey took her first teaching job, in Indianapolis’s Perry Township schools in 1995. “Understanding the school desegregation process as a new seventh-grade social studies teacher would become an unexpected new norm,” she writes. “The culture in my Perry Township middle school was clouded with misunderstandings and undertones of racism, mixed with strict protocols to make sure the court-mandated guidelines were followed. I was greeted with stories of past racial tensions by complaining faculty members who often shared, with boldness, their unwillingness to comply with the new rules. This behavior was unexpected and unwelcome, and it did not take long before I became aware of the historical noose now attached to my career.” Read the full essay.

Read more about the cases, plaintiffs and oral histories at The74Million.org/Brown65. Get the latest news about school integration, and the classrooms that are successfully closing the achievement gap, delivered straight to your inbox; sign up for The 74 Newsletter.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)