Hosting a Spirit Week, Rejiggering a Physics Lesson, Grappling With Attendance: How NYC Teachers Are Adjusting to Week 1 of Remote Learning in the Nation’s Largest School District

New York City this week began the nation’s largest remote learning endeavor amid the coronavirus pandemic, shifting its 1.1 million-student district and 75,000 teachers online likely through the end of the school year.

In the days leading up to the transition, NYC educators scrambled to reformat and reconceptualize how they teach, with only three days of professional development and one day of remote planning. Online tools like Google Classroom are new for many. Some have students who are still waiting for devices to have at home.

Educators interviewed by The 74 say it’s going to be a very iterative process and — at least for now — one that looks different for every school and teacher.

“It’s been so crazy just to get acclimated to this,” said Susan Cohen McAulay, a special education teacher at A. Philip Randolph Campus High School in Harlem.

“I’m very much in a one-day-at-a-time kind of mode right now,” added Suraj Gopal, who teaches multiple subjects at the Special Music School on the Upper West Side. “My goal is to get as much feedback as I can” and go from there.

Teachers’ experiences this week have hinged on a variety of factors, from their own tech savviness to the grade level they teach to the socioeconomic status of their students and the buy-in of their kids’ parents.

Gopal, for one, has been heartened to see most of his high schoolers signing on, but he is already revising part of his online teaching method after many flunked the first physics assignment. McAulay is scrambling to get her students with disabilities online and engaged. A tech-savvy Brooklyn teacher is trying to re-establish a sense of normalcy with a spirit week for his elementary schoolers. Another educator teaching low-income preschoolers in the Bronx is struggling to get parents — who are now especially critical partners in teaching young children remotely — involved.

This new reality likely isn’t going away anytime soon. Mayor Bill de Blasio acknowledged Monday that students are unlikely to return to their classrooms this year, despite hopes of schools re-opening on April 20. In a Skype call with Inside City Hall‘s Errol Louis Monday night, Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza urged teachers, parents and the broader community to heed two words — flexibility and patience.

“We’re literally building this plane as we fly it,” Carranza said. “This is a massive shift for all of us.”

Here’s how Week 1 is playing out for a handful of teachers across the district:

Scott Dyer, second-grade teacher, P.S. 251 (Brooklyn)

Going into this week, Dyer’s biggest concern was, “Are [students] going to be able to log on? And follow along?” He co-teaches a class of 23 second-graders in Brooklyn’s Flatlands neighborhood.

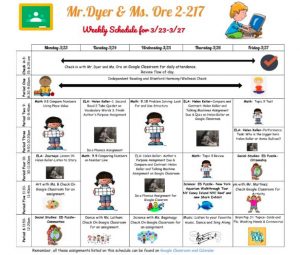

Dyer and his co-teacher were already well-versed in using Google Classroom prior to Monday’s launch. They’d sent guidance early to parents on Class Dojo on how to sign their kids up and navigate the system, and they’d designed a colorful schedule outlining the class lessons for the week. They’d ensured that their five students who didn’t have a device at home got a hold of one before lessons began.

Even so, the week began slowly, with 11 of his 23 students logging in Monday to complete a math assignment on place values via enVision and to listen to a read-aloud story about Helen Keller. By Tuesday, though, that number had jumped to 18 students. The goal for the end of this week, Dyer said Tuesday, is to get kids and parents feeling “at ease” with the online tools.

It’s a process. He was his wife’s “technical person for two parents” on Monday, he said — his wife also teaches — on top of fielding his own class’s questions. Educators have been messaging him for tech help, too.

The transition to remote learning is equally jolting for his young students, and Dyer and his co-teacher wanted to maintain some semblance of normalcy. So this week is not only a foray into remote learning — it’s also spirit week.

Monday “was Superhero Day, so I wore my Deadpool shirt, and kids were posting pictures of themselves with their favorite superhero,” he said. Tuesday was “take a picture with your favorite stuffed animal.” Wednesday was pajama day.

Re-establishing normalcy is also a priority for a pre-K teacher in the Bronx, who — like a few other educators contacted by The 74 — was hesitant to be identified because she’s not tenured.

On Monday, she videotaped herself doing the daily “morning meeting,” which she said typically includes activities like naming the day of the week and singing a song. She also posted a video of herself reading a story called “Not a Box” in Google Classroom to get her youngsters thinking creatively.

But only a quarter of her kids’ parents signed them on that day. And only one more did on Tuesday.

With her 4- and 5-year-olds now at home, whether they tune in is wholly dependent on both their parents’ ability and willingness to assume a homeschooling role. Many of her students come from low-income households; some are being raised by their grandparents. If the child has older siblings, and the family has few resources and limited devices, she fears their learning won’t be a priority.

For the rest of this week, she said, she plans to keep reaching out to her students’ parents and caretakers, encouraging them to participate.

“I’ve given them all the information,” she said. “I’m worried a few of them aren’t going to care enough to keep this going.”

Susan Cohen McAulay, special ed teacher, A. Philip Randolph Campus High School (Harlem)

McAulay oversees five classes, mainly teaching English to sophomores. Two are “self-contained” classrooms that only serve special education students with Individualized Education Programs.

Teaching students with special needs remotely is “daunting,” she said, noting how she has “certain students who really struggle with directions and benefit from being spoken to” directly. She’s particularly concerned about one student who needs dedicated attention but is still awaiting a home device to log in.

“Teaching online takes away a whole dimension from teaching,” she said, “and it particularly affects students with disabilities.”

As of Tuesday night, McAulay felt as if she was drowning in problems that she hadn’t initially thought about in the pre-planning stages. She’d just decided to add a daily “Do Now” morning assignment to her lesson plan after realizing earlier in the week that there was no way to track who was actually online. While she’s added her school’s speech therapist to her Google Classroom page, she doesn’t know the extent to which they are connecting with students who require those specialized services.

McAulay added that schools are now expected to devise a remote learning plan for how students with IEPs will be accommodated in this new online setting. But she’s unclear whose responsibility that is and how that obligation will be met.

“Just generally — not pointing to my school but the [Department of Education] as a whole — there hasn’t been a lot of planning, I think, in terms of organizing all of this,” she said.

Suraj Gopal, high school teacher, Special Music School (Upper West Side)

Gopal wears “many hats” at his small high school; he’s licensed in special ed but also teaches AP computer science, physics, chemistry, geometry and global history.

He and other colleagues opted to forgo live lessons — at least initially — taking into account families who may not have unique devices for every child. So Gopal’s roughly 90 students logged into Google Classroom on Monday and Tuesday to an array of Google Slide decks, sample problems and video resources like “demonstrations [for physics and geometry] that show me discussing and solving problems by hand.”

So far this week, there’s been close to full online participation, Gopal said. Even starting Monday, students were “attending [virtual] office hours” and beginning “to ask detailed questions,” which he found heartening. The school — which serves K-12 but operates K-8 and high school in different buildings — is high-performing and enrolls more than 40 percent white students.

With the positives came some kinks. Many of Gopal’s physics students, for example, “did poorly” on the first assignment submitted late Monday night, he said. That raised a number of questions: whether to offer make-up assignments, how to schedule virtual review sessions for students without stepping on their other teachers’ toes, and how to rejigger teaching a complex subject like physics remotely.

“There’s so much in terms of the richer, conceptual parts of the course that I haven’t figured out how to communicate yet,” said Gopal, who worked as a summer intern for The 74 in 2016. For now, he said, “I’m going to design something a little more robust. I’m going to also make an instructional video of me in general going through the [Google] slides and giving examples of takeaways.”

When considering make-up assignments moving forward, Gopal said he does worry about student accountability.

“I can operate in good-faith estimates of my students for the most part; they’re hardworking and honest,” he said. “But here and there, you wonder if you’ll encourage poor work habits. … It’s tough.”

Adam Feinberg, a high school social studies teacher The 74 interviewed last week, was similarly homed in on how to nurture a good online work ethic.

Feinberg, who teaches at City Polytechnic High School of Engineering, Architecture, and Technology in Brooklyn, said he planned to assign more creative writing assignments — like journaling and independent research on a topic a student chooses that fits within a study unit — that make it “really easy to see a student who’s putting in the effort.”

“All of our students” are coming back to school after the pandemic ends, he said. “And then what? What did they learn, and what work habits did they learn, and what did they not learn? That’s my concern.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)