Exclusive: Data Show Girls in NYC Schools Receive Special Ed Services at Disproportionately Lower Rates Than Boys. How Race and Gender Drive Inequities

Little is known about girls — especially girls of color — who are learning with disabilities in the nation’s largest school district.

Amid a year of damning reports and investigations that unveiled continuing failures within New York City’s massive special education system to evaluate and provide timely supports to tens of thousands of students, the city’s Department of Education released an annual report in November touting a record 84.3 percent of special education students receiving their full required services in 2018-19.

Also within the 47-page document was a less heralded statistic: There were 130,885 boys with special education accommodations in NYC schools that year, versus 66,995 girls, despite a fairly equitable distribution of both boys and girls systemwide.

That boys far outnumber girls in special education is a historically unchanged and seemingly accepted data point — girls make up about a third of students with special education supports nationally as well — and gender appears largely absent in mainstream conversations about the system’s inequities. Girls with special education accommodations have “never come up” in discussions by the Panel for Educational Policy, the city DOE’s governing body, said Lori Podvesker, a panel member for nearly six years, director of disability and education policy at INCLUDEnyc and the mother of a son receiving special education services. “Never. I’m on the record for that.”

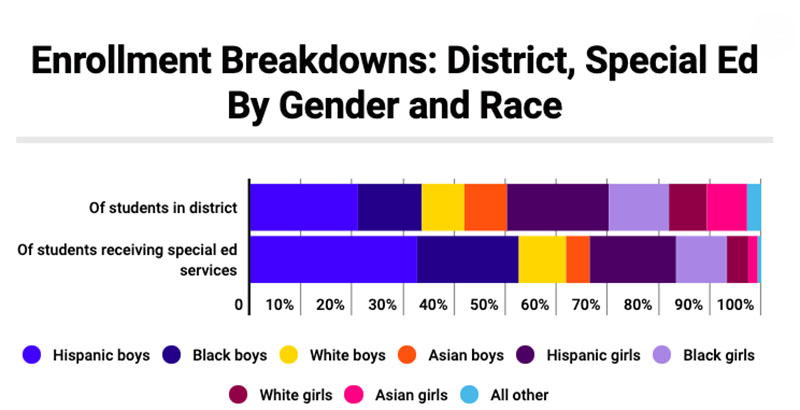

Much of the discourse in New York City and nationally has centered on race and the question of whether students of color, especially black males, are being over- or under-identified. An in-depth analysis by The 74 of federal civil rights data trained the lens on girls across racial groups, revealing that Hispanic, black, white and Asian girls in NYC are all receiving special education supports at noticeably lower rates than their respective shares of the city’s roughly 1.1 million public school students. The disparity is starkest for Asian girls, whose representation plummets by 77 percent when comparing their enrollment across the district, at 7.84 percent, with their enrollment in special education, at 1.81 percent.

Meanwhile, every male racial group, apart from Asian males, reported the inverse trend, making up a larger portion of students in special education than in the city school system as a whole.

While there isn’t a “correct” rate of identification, experts say the findings add to existing notions that some girls may be under-identified for special education accommodations compared with their male peers. Though girls are equally entitled to that assistance under federal law, theories suggest they may not be getting services as readily for reasons that are more rooted in how girls are perceived than a likelihood of boys having more learning disabilities.

“It’s a big deal,” said Cheri Fancsali, the deputy director of the Research Alliance for New York City Schools, who this year published a deep dive report on the city’s special education data. “There may be a lot of girls who are underdiagnosed and who could really benefit from special services, and they aren’t getting it. And on the other side of the coin, if some boys are being inappropriately referred to special ed services … they may be missing out on access to a high-quality, general ed curriculum.”

A DOE spokeswoman declined to comment on how the district tailors supports for girls with disabilities specifically, writing in an email Friday that accommodations are “universal and appl[y] to all students based on need, not on gender.”

Data gleaned from the analysis also revealed that among girls who do receive special education services, there are racial patterns that mirror their male peers. For nearly every 5 black or Hispanic girls, there is 1 white or Asian girl. (In the city’s public schools, Hispanic and black girls outnumber white and Asian girls 2 to 1). The special ed discrepancy, Fancsali noted, further underlines the importance of looking at race and gender data together — and the need for even more detailed demographic information on these students.

“Gender and race intersect in complex ways,” said Rachel Fish, an assistant professor of special education at New York University whose research explores how special education identifications hinge on a slew of factors, including who the students are, where they attend school and their particular needs. “We treat these gender questions as if they’re race-less in a lot of popular discussions, and it’s really important to treat them with the nuance of understanding that intersectionality is crucial here.”

The 74 sought out the data after noticing that the 2018-19 DOE report broke out total counts of students with special education plans by students’ race and language or students’ gender and language, but not in a way that allowed the public to see how many girls or boys of each race existed in both the special education system and in the school district more broadly. After being told by the DOE that it doesn’t break down the numbers that way, The 74 extracted it from the Office for Civil Rights’ most recent school-level database.

The special education system in New York City is vast, serving upward of 200,000 students across K-12. Its handling of these students’ individual learning needs has been widely criticized, with recent reports exposing skyrocketing special-education-related complaints and severe delays in addressing them. Even with the revelation that 84.3 percent of students in special education last year received all of the services mandated by their Individualized Education Programs — up from 78.4 percent in 2017-18 — organizations such as Advocates for Children of New York have stressed that there are still nearly 29,000 students not getting their full, legally required supports.

The DOE spokeswoman noted Monday that the district this year has invested an additional $33 million citywide in special education resources, which includes the hiring of about 200 clinicians to improve the accuracy of identifications and the timeliness and quality of services.

“We have unified and streamlined instructional supports — including professional development and curricular resources and materials — to make rigorous teaching accessible to all learners, including students with disabilities,” she said.

‘We can ignore behavior from girls’

When Marisol Nunez recalls how her daughter was left behind in school, it brings her to tears.

Emely, a Latina student in NYC, was still reading at a second-grade level when she was 14. And although school staff had brought Emely’s floundering academics to her mother’s attention, it was years before anyone told Nunez a crucial detail: Something could be done about it.

“They just started to say that she was struggling, but I never heard anything from the district that she needed special support,” Nunez said in Spanish through a translator. She spoke on behalf of her now 17-year-old daughter, who, after advocate intervention, is receiving services for a language disorder and learning disability.

Emely had been overlooked for help — something that may happen with girls more often than boys. Looking at the breakdown of student enrollment in NYC:

● Hispanic girls make up 19.84 percent of students in the district but 17.05 percent of all students with special ed services. Hispanic boys make up 21.05 percent and 32.74 percent, respectively.

● Black girls make up 11.87 percent of students in the district but 9.92 percent of all students with special ed services. Black boys make up 12.62 percent and 19.90 percent, respectively.

● White girls make up 7.43 percent of students in the district but 4.10 percent of all students with special ed services. White boys make up 8.13 percent and 9.15 percent, respectively.

● Asian girls made up 7.84 percent of students in the district but 1.81 percent of all students with special ed services. Asian boys make up 8.47 percent and 4.55 percent, respectively.

The information, to note, has its limitations. It covers the 2015-16 school year — the most recent year these broken-out counts are available. The NYC DOE’s year-over-year totals of boys versus girls with special education plans suggest, though, that the gender proportions have budged only about 0.3 percent since then. And although the database tallied students of all disability classifications who are receiving accommodations mandated under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, some students may still be missing. Per privacy laws, if a school identified fewer than three students with special education supports in a particular gender or racial group, that data was omitted.

Experts point to a few established theories for why these gender disparities in special education within New York City public schools and nationally might be happening, and why they persist.

“It could be as simple as boys tend to be more physical, and sometimes behavior can’t be ignored from boys as much as we can ignore behavior from girls,” INCLUDEnyc’s Podvesker said. She added that with disabilities like attention deficit disorder, students “could be really dreamy and spacy and just always out of it. And since we tend to see girls as being more passive, we don’t always associate that with learning problems.”

This could especially be the case if teachers aren’t readily trained on how to recognize different disabilities, Podvesker said. The DOE confirmed Monday that teachers have to be trained on identifying students with disabilities, noting that per New York state regulations, “all teacher candidates for all subjects and levels must receive coursework on working with” these students. Prospective educators, for example, have to pass a certification test that includes a section on understanding “the characteristics, strengths, and needs of students with disabilities” before obtaining their teaching license.

Another factor, NYU’s Fish said, could be some teachers’ and parents’ perceptions of girls’ academic prowess compared with their male counterparts. “If [a teacher] thinks that girls are less academically capable, then that means that if a girl is performing at a lower level in math, for instance, the teacher might say, ‘Yup, that’s about what I expected,’” she said.

Parents could also be reluctant to seek special education accommodations for their kids “because of the stigma associated with it,” Fancsali added. Negative ramifications frequently thought of with special education include restricted access to a rigorous curriculum, lower expectations and segregation from peers in traditional classes.

As a mother of two daughters, Nunez said she can’t speak to whether Emely’s gender influenced her access to services. She does believe, though, that Emely being Latina contributed to the delay.

The system “undermines our culture and our people,” she said.

Girls ‘not a monolithic group’

Considering race along with gender adds more nuance to the special education landscape. It also magnifies its complexity and raises more questions.

While The 74’s analysis surfaced the common thread of girls receiving special education supports at disproportionate rates compared with almost all boys, it also found that the vast majority of girls with those services — nearly 82 percent — were black and brown girls.

On the one hand:

● Hispanic girls make up 51.58 percent of girls in special ed, compared with 41.05 percent of girls in the school system.

● Black girls make up 30.02 percent of girls in special ed, compared with 24.56 percent of girls in the school system.

On the other hand, the inverse:

● White girls made up 12.40 percent of girls in special ed, compared with 15.37 percent of girls in the school system.

● Asian girls made up 5.46 percent of girls in special ed, compared with 16.22 percent of girls in the school system.

“This is not a monolithic group,” Fancsali said. The data “makes that point even more strongly.”

The notion that students of color may be overrepresented in special education isn’t new; a federal judge in September, in fact, ordered the U.S. Education Department to implement Obama-era regulations that address concerns that students of color, especially those who are black, are disproportionately identified as having disabilities. President Donald Trump’s administration had sought to delay implementing those regulations for two years while it studied the issue further.

As with the broader gender disparities, there are existing ideas about how a girl’s race could factor into whether she’s referred for special education services. For black girls especially, “when there’s a behavioral challenge … it’s something that is very much noticed” and often acted on punitively, Fish said. Research shows that black girls are six times as likely to get out-of-school suspensions as their white counterparts, written off as insubordinate and aggressive because of race and gender bias.

“There is a very unique experience to being a black girl in schools that isn’t just being a girl and being nonwhite,” Fish said. “Being black in America and being a black girl in America, that is a particular social location that’s oppressed in very specific ways.”

Fancsali also noted that for girls who are English language learners, many of whom are Hispanic, it could be that “sometimes their development of English is mistaken as a disability, when really it’s just the natural progression of developing English language.”

Some academics, such as Paul Morgan, challenge the notion that bias is the catalyst for over-identification — and even dispute the idea of over-identification altogether. Morgan, an education professor at Penn State University, previously told The 74 that “historical and ongoing racial segregation” heightens the risk for disabilities among students of color.

“Children of color are more likely to be born with low birth weight or experience fetal alcohol syndrome or be exposed to lead,” he said, causing an unequal distribution in disability across racial groups.

Addressing what appears to be a comparative under-representation of white and Asian girls, Fancsali speculated that more affluent white families may have the resources to set their kids up with private services outside the system, leaving them undetectable in the federal database. Speaking anecdotally, INCLUDEnyc’s Podvesker added that the stigma attached to special education can be a particular deterrent to Asian-Pacific American communities.

“It’s societal; it’s norms. Culture plays into it,” Podvesker said. “It’s not just teachers. And I hate making excuses and letting the DOE off the hook, but it’s the truth.”

A need for built-in screening

Experts interviewed for this story all agreed that more information about these girls is needed to draw any sound conclusions about under- versus over-identification.

Fancsali wants to know these girls’ specific disability classifications as well as their socioeconomic statuses. Fish is also curious about their test scores; are these girls performing better academically than their male peers?

“The reality is a much more nuanced situation and can’t be easily explained with a single pattern or trend,” Fancsali said. “And it speaks to the complexity of identifying students and correctly assessing their educational needs.”

When asked what the district could be doing better to help girls needing special education supports, Podvesker reiterated the urgency of training teachers on the central characteristics of disabilities and what they look like in the classroom. For example: distinguishing between the hyperactive and impulsive behavior of students with ADHD and the potentially lackadaisical, inattentive nature of students with ADD.

“It’s really that basic,” she said, adding, “All school staff needs it. Bus drivers, bus attendants need it.”

Expounding on New York state’s regulations for teachers, the DOE spokeswoman noted Monday that coursework required for certification reviews “the categories of disabilities; identification and remediation of disabilities … individualizing instruction; and applying positive behavioral supports,” among other things.

Fish said the district should also ensure that it’s prioritizing early intervention for students “as soon as they are starting to show some challenges.”

“I think we need a lot of built-in screening mechanisms,” she said. “I know that teachers are stretched really thin, so we can’t just say, ‘OK, teachers, take one more thing on’ — but we need staff supports in schools to help teachers identify kids as early as possible in the school year and as early as possible in their school career.”

In that vein, the DOE spokeswoman said the district employs a “Multi-Tiered System of Support” that “provides services and intervention as soon as the student demonstrates a need,” and it especially targets schools “with disproportionate referral rates, providing the right interventions on the front end, so that students aren’t referred to special education when there were potential interventions or core instruction improvements that could have been made.”

For Nunez, her request of the district wasn’t about data or programs or money. It was an emotional plea.

District officials “should keep in mind that their actions really affect families,” she said. “Be a person. See others.”

She added, “As a mom … I just want the best education, the best life, for my daughter.”

Staff reporter Esmeralda Fabián Romero provided translations for this article on behalf of Marisol Nunez.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)