Hope Chicago: A Unique Scholarship That Sends Parents to College, Too

CEO and former district schools chief Janice Jackson says the “two-generation” approach offers families powerful incentives to graduate.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When Nilsy Alvarado graduated from high school in Chicago nearly two decades ago, she had big plans to attend college.

It was 2004. A Honduran immigrant who’d arrived with her family in the late 1990s, she secured a slot at a local community college, but reality hit when a counselor revealed her first semester’s tuition: $700, up front.

“I didn’t have that kind of money,” Alvarado said. And her high school offered scant advice on how to pay for it. “So I started working,” first as a daycare assistant, then in a series of manufacturing jobs, all while raising two kids on her own.

Now 37, Alvarado works for Pactiv Evergreen, the manufacturer of those ubiquitous plastic Hefty cups.

But this fall, 19 years after she graduated from high school, she’s about to get a second chance at college, compliments of an unusual benefactor: her oldest daughter.

Alvarado’s first-born, Yolany Baltazar, is among the first beneficiaries of Hope Chicago, an unusual experiment in college access. Like many “college promise” programs, it essentially offers a free ride to a bachelor’s degree, covering tuition and fees for students who graduate from high school and persist through college.

But in Baltazar’s case, there’s a difference: Once she made it through her first semester, Hope Chicago made the same life-changing offer to her mother.

It’s part of a “two-generation” approach to attacking poverty, said Janice Jackson, Hope Chicago’s CEO. She noted that many college access organizations that support low-income families often “tinker around the edges, instead of going to where we know we need to go: making sure that there is much more of a pathway to the middle class.”

Advocates say research shows that greater access for both groups increases parents’ earnings and encourages kids to stay enrolled long enough to graduate.

‘A different conversation’

If Jackson’s name sounds familiar, it’s because she spent four years, from 2017 to 2021, as CEO of Chicago Public Schools, the fourth-largest district in the U.S.

“The thing about Hope Chicago is [that] when you first hear about it, it almost seems too good to be true,” Jackson said. “And I think that’s the response that a lot of people have.”

Once they sit with the idea a while, she said, many begin to ask why it isn’t true everywhere. “Why don’t we have a system in place so that kids across this country, quite frankly, can continue their education, and that finances are not the biggest barrier to them?”

At the moment, Hope Chicago has agreements with just five city high schools, offering graduates and their parents free access to 28 colleges, most of them Illinois public four-year and community colleges, along with a handful of private institutions.

Students must gain admission based on their own academic achievements — Hope Chicago doesn’t ask colleges to change their admissions criteria. And the program has no GPA cutoff, so students remain eligible to continue as long as they’re enrolled in classes.

But those who drop out also make their parents ineligible — a bit of subtle, intra-family peer pressure to stay in the game.

“Students obviously can go if their parents don’t go, but parents cannot take advantage of this unless their child is enrolled in school full-time,” Jackson said. “So they have an incentive, right? If I’m a parent and I’m in school and things are working out, but my child wants to drop out, that’s a different conversation.”

She said Hope Chicago deliberately chose its five high schools for the greatest possible impact, working in buildings that had seen “decades of chronic disinvestment,” lower achievement levels and graduation rates.

The focus, she said, is on helping the entire school. “It’s really about making a big difference.”

Baltazar, 20, still remembers the day she learned about the program in February 2022, at an assembly at Benito Juarez Community Academy on Chicago’s west side.

She texted her mother to warn her to stay off social media until she could deliver the news herself, Baltazar said. “When she picked me up from school, she was like, ‘What have you got to tell me?’ I’m like, ‘Mom, we get to go to college debt-free!’”

Alvarado was dumbstruck. “I was really happy if she got the opportunity to go [to college], just herself or my kids,” she said. “But for me, it was a little bit hard to process.”

In a few years, Alvarado’s younger son, 16-year-old Adrian, also a Hope Chicago scholar, will be able to attend college for free when he graduates from Benito Juarez.

‘In the center of a tornado’

The program launched in early 2022, with a $20 million investment from two philanthropists, Pete Kadens and Ted Koenig. Jackson wants to raise another $1 billion over the next decade to expand it and make more families eligible.

Recent research shows that these more educated parents will almost certainly earn more money — about $4,000 annually, according to a 2018 study, even though many are already years into their careers.

But multi-generational college enrollment not only benefits parents. It also has a significant “spill-over effect” on their children. One reason is obvious: Parental education is a strong predictor of whether a student will attend college.

A recent study by City University of New York economist Clive R. Belfield noted that children whose parents are college graduates are three times as likely to attend college themselves. Investing in multigenerational college-goers, he said, is “economically efficient.”

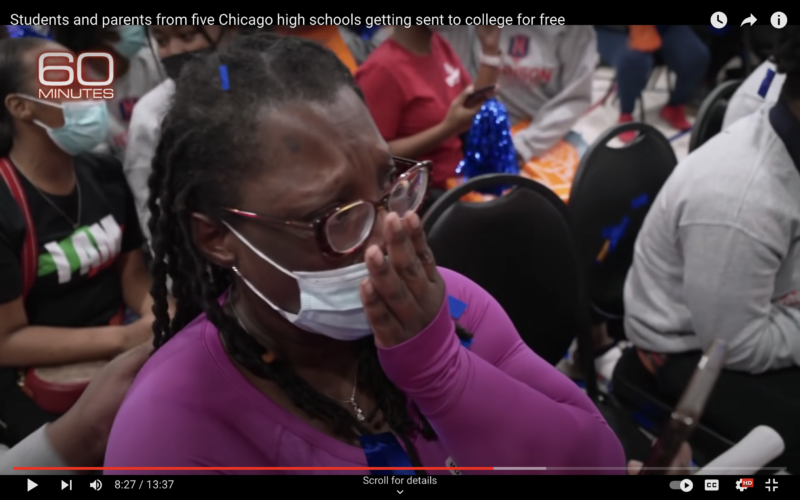

When Hope Chicago came to Ajani Cunningham’s school, Johnson College Prep, in spring 2022, it was co-founder Kadens who told an assembly of students they’d be going to college for free. Cunningham’s mother, Yolanda White, was filming the moment with her mobile phone and began crying. But then Jackson, Hope Chicago’s CEO, joined Kadens onstage and told the parents they were also eligible for free college. “And then the uproar was, like, magnified a thousand times,” Cunningham recalled.

“It was almost like … what people describe as being in the center of a tornado,” White said. “I think [Kadens] broke my brain because I could not react. I just sat there.”

But stunned as she was, she knew immediately what she would do with her good fortune: finish her culinary education.

The 50-year-old mother of five had earned an associate’s degree at the for-profit Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Chicago in 2014, which closed in 2017, part of a national wave of for-profit closures.

She studied to be a pastry chef and nutritionist and has spent the past few years running an online bakery called Miss Landa Cakes. She also created and teaches a handful of home economics and mentoring courses for Chicago Public Schools.

White dreams of earning a bachelor’s degree and teaching people how to source and eat higher-quality, locally grown food, especially in so-called urban “food deserts.” She knows these issues firsthand: In the eight-year period when she and her five kids were homeless, White recalled, “I had to make $20 work” for a week’s worth of meals. “And they were never hungry.”

White plans to study at Kendall College’s Culinary Arts School in Chicago, but she’s holding off on enrolling for a year while she figures out how to cut back her hours at the district. She also needs to put the online bakery on hiatus.

“When someone presents the physical manifestation of a lifelong dream to you,” she said, “you kind of have to pay attention to that.”

Meanwhile her son will matriculate this fall at Loyola University Chicago, thanks to Hope Chicago, studying psychology while planning for law school and a career in civil rights law.

‘A different life’

The organization’s efforts unfold as the district faces an odd mixture of crisis and confidence: While Chicago Public Schools in 2022 boasted a record-high graduation rate of 83%, just one-fifth of high school students were reading and doing math at grade level, according to the Illinois Policy Institute. And nearly half of students missed at least 18 days of school.

Hope Chicago says its work is already having an impact: An April report by Belfield, the City University scholar, found that college enrollment rates averaged 74% — a 17% increase — in the organization’s first year partnering with the five schools.

The program is looking to expand — at the moment it serves about 4,000 students, and is fund-raising both publicly and privately with hopes of announcing more high schools in the future.

While the two-generation approach is unique, the program operates in the tradition of “college promise” programs that for nearly 20 years have guaranteed tuition-free access to higher education. The movement began in 2005, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and now counts more than 300 programs in at least 32 states, according to the Campaign for Free College Tuition.

The Michigan program offers Kalamazoo Public Schools graduates up to 100% of tuition and fees at in-state public universities and community colleges. A 2017 study found that six years after high school graduation, students in the program had higher rates of college credential attainment — 46%, up from about 36% before 2005.

While the researchers said making college free won’t necessarily ensure that more students enroll, they found that offering a “simple, universal, and generous scholarship program” can significantly increase educational attainment, especially among low-income students.

Last spring, Baltazar finished her first year at Illinois State University in Normal, Ill., about a two-hour drive south of Chicago. Studying biology and pre-dentistry, she spent much of her freshman year adjusting to dorm life.

Baltazar had the advantage of bunking with a friend she’d known since middle school. She made new friends by simply leaving the dorm room door ajar and playing music.

Meanwhile, her mother is putting the finishing touches on an application to attend Western Governors University, an online program, in August. She plans to study finance while keeping her job at Pactiv Evergreen, and still can’t get over her good fortune — or her daughter’s.

“I think just the idea of her going to school without any debt, and including myself, is just like …” She paused for a second. “In four or five years, this is just a different life.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)