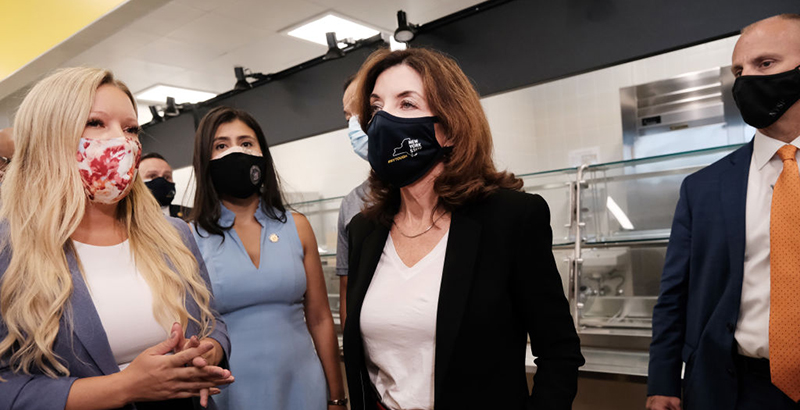

Gov. Hochul’s Calls to Fully Fund New York Schools, Pump Up Teacher Pipeline Praised — But More Details Wanted

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, Jan. 18

Teachers, administrators and child advocates say they’re impressed with Gov. Kathy Hochul’s proposal to improve education by shoring up the employee pipeline and releasing billions of dollars in additional aid to schools, but they’re unsure if her approach will bring lasting change.

In her first State of the State address, delivered Jan. 5 amid a surge in the ongoing pandemic, Hochul shared her plan to address a broad range of issues, from public safety to affordable housing.

She also stressed the importance of educational opportunities for adults and safe, open schools for children, saying, “The role of a teacher is irreplaceable in a child’s life and as the past two years have hammered home, they’re irreplaceable in a parent’s life, too.”

Hochul, sworn in as the state’s first female governor in August after Andrew Cuomo left the post in disgrace, is running for a full term. Former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Tuesday he would not run for governor, while another another high-profile candidate in the June Democratic primary, New York Attorney General Letitia James, dropped out last month. The latest polling numbers, also released Tuesday, now show Hochul leading by more than 30 points her remaining Democratic rivals, New York City Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and Long Island state Rep. Tom Suozzi.

While her political fate has yet to be determined, educators and advocates say they’re witnessing a shift in tone from Cuomo to a leader who has a more cordial relationship with city and state power players. But it’s unclear how or when her vision for public schools might become reality. More will become known when Hochul releases her first proposed budget Tuesday.

Randi Levine, policy director for Advocates for Children of New York, which works to improve education for low-income students, said Hochul’s priorities are in line with her own, especially as it relates to added funding. But she’d like to know more.

“As is the case with a lot of these proposals, we are eager to see the details,” she said.

Hochul wants to provide incentives to attract more teachers and school workers — this includes waiving the income cap for some retirees and expanding alternative certification programs — and encourage paraprofessionals to boost their skills, among myriad other initiatives.

Her plan was informed by the state’s current teacher shortage, which is expected to worsen: New York needs approximately 180,000 new teachers over the next 10 years to make up for the loss, according to the state teachers union.

Hochul earlier announced the state would phase-in full funding of Foundation Aid to New York school districts — the money comes after a decades-long legal battle — by the 2023-24 academic year. Foundation Aid takes into account school district wealth and student needs in crafting a more equitable funding distribution and will add $4 billion to school coffers through the next three years.

Darlene Cameron is principal at The STAR Academy PS-63, a small, pre-K through fifth grade campus in Manhattan’s East Village where 75 percent of students qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, a key indicator of poverty. Her students, like many others throughout the state and nation, have suffered mightily during the pandemic.

Schools across the country continue to face closure as the Omicron variant surges, further disrupting learning.

Cameron supports the strengthening of the education workforce but isn’t sure how — and when — the results will be seen on her campus, which is in desperate need of literacy experts to help students with comprehension, dyslexia and trouble with writing.

“Right now, all schools are supposed to have one literacy coach for kindergarten, first and second grade,” she said. “Mine is on extended health leave. We are in mid-January and I’ve had no literacy support all year long yet my superintendent expects me to have students make two years’ worth of progress in one year.”

Sharon Collins, a math teacher at New Heights Academy Charter School in Harlem, said she, too, would like to see additional funding for more staff, including mental health workers, another key part of Hochul’s plan. The governor proposed state-provided mental health grants to schools and matching funds for those that make good on using federal dollars for this same purpose.

“Schools have never had enough counselors and now we have students who are really in need and in crisis, dealing with the loss of family members and with being out of school for such a long time,” said Collins, a member of Math for America, a nonprofit that supports New York City’s strongest math and science teachers.

The Foundation Aid comes at the same time New York state is receiving $8.9 billion in federal COVID relief monies meant to support summer and afterschool programming, the hiring of added staff, upgrades to ventilation and professional development among other expenditures.

But even as the state is flush with cash, educators worry schools won’t get what they need.

Jodi Friedman, assistant principal at Cameron’s campus, is concerned about teacher retention, adding Hochul might consider improving working conditions and compensation if she aims to keep existing employees.

Teachers, Friedman said, are exhausted, overworked and underappreciated, burned out from a pandemic which has forced many to work longer hours as they struggle with distance learning demands and chronic absenteeism among their students — all while trying to maintain their own health.

“This idea of giving everything of yourself to help others can’t continue,” she said. “It’s not sustainable.”

And while the pandemic has been a recent challenge, schools have, for years, taken on problems that should be addressed elsewhere, she said: What schools really need are robust social services to help families off campus.

“If schools are the only way children get food, health care or heat, that is a problem,” Friedman said. “Teachers aren’t just teaching, but taking on … all of the ills of society.”

Jasmine Gripper, executive director of Alliance for Quality Education, a statewide labor-backed advocacy group, said for all Hochul’s talk of recruiting more staff, the governor overlooked a key element.

“One of the things missing was an intention on diversity,” Gripper said, adding New York has done a poor job of recruiting and retaining teachers of color, a problem that could be remedied through “grow-your-own” initiatives, stronger relationships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities and proposed changes in the certification process.

Still, she was heartened by the governor’s overall commitment to the state’s school system: Her organization was key in pushing for the release of Foundation Aid.

“The state is continuing to maintain its promise,” she said. “So that is really encouraging.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)