‘Generation Citizen’ Excerpt: 3 Things Adults Can Change Today That Will Empower More of Their Children to Live a Political Life

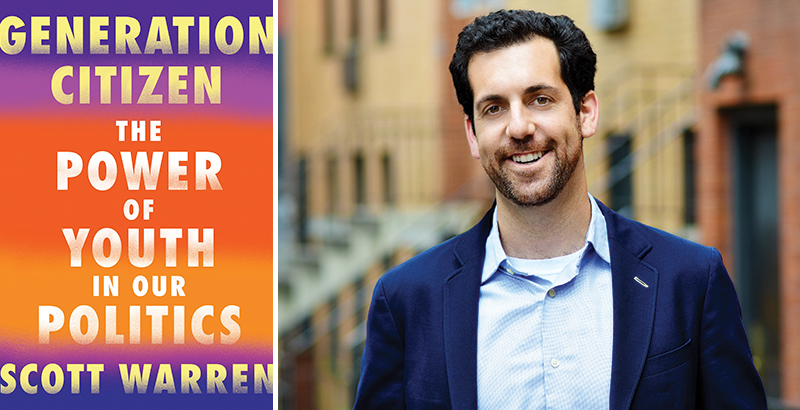

Below is an excerpt from Generation Citizen: The Power of Youth in Our Politics by Scott Warren. Also of interest: Laura Fay’s recent news feature on action civics and the organization Generation Citizen, and Kevin Mahnken’s recent deep dive into Democracy Prep, a school network that puts citizenship at its center.

Time For a (Youth-Focused) Change

Especially in the midst of an unprecedented political decline in the values of our democracy, young people feeling compelled to take action is not necessarily sufficient on its own.

In order for those political journeys to happen effectively, we need to enact certain reforms to our democracy.

There are many potential changes that would create a more equitable and effective democracy in which all voices are represented in our government: better voting laws to ensure all individuals can vote, less gerrymandering and splitting up congressional districts to ensure certain parties remain in power, less money in politics to rig the game. Much has been written about these reforms.

In keeping with the theme of elevating youth voices in politics, I argue for three specific but fundamental transformations we can make to help lift up young people as real and legitimate political players. These structural changes would ensure that more young people are able to live a political life:

1. Ensure Schools Promote Democracy

Generation Citizen works to educate young people to become active citizens through promoting civics education in the classroom. So, obviously, I’m going to be in favor of more civics education for young people. We need to make sure that an equitable, effective, and holistic civics education is available to all students. It would help us ensure that more young people are able to participate in our political process, just like the students we saw come out of Parkland.

At the same time, of course, a single civics class is not enough. A more comprehensive solution to ensuring that all young people have the potential to become active political citizens requires a revamped vision of the entire purpose of schools.

Currently, schools have become overly focused on preparing students for college and careers, with an extreme and misguided emphasis on high-stakes standardized testing. This obsession with testing leaves students inadequately prepared to participate in democracy.

The historic and ultimate mission of public schools is to educate the next generation of citizens to participate in and lead our democracy. That is, after all, why our founders created free public schools: to ensure that citizens would be capable of self-governance, from generation to generation.

We have not actualized that rhetoric and vision in our schools. Instead, schools today generally focus on subjects that have little relationship to one another. Content is emphasized over skills. Individual success over the collective well-being.

This starts with how we teach classes. Science, which, by its nature, involves observation, investigation, evidence, and application, is often taught in isolation from other subjects and in seats, rather than through exploration, experimentation, and evidence. The study of history too often involves reading brief paragraphs in a textbook; students aren’t taught the complex history of their democracy.

A focus on rote learning, a staple of the American educational system, will not lead to the kind of citizenry necessary to maintain a democracy. Nor will an overemphasis on standardized tests lead to practiced real-life engagement in conflict resolution, research, and other activities that require critical thinking.

It is ineffective to teach civics in a public educational system that forces young people to demonstrate their abilities through standardized tests. Such a rigid intellectual climate is at odds with the democratic process and contrary to how many of the originators of the public school system envisioned the institution’s role. While the Founders wanted to ensure that our democracy could continue to function through an informed citizenry, these visions were more words on paper than actual practices.

We need to articulate a more inspiring, citizen-centric vision to our public schools. We can, and must, reimagine schools as laboratories of democracy, enlisting young people as collaborators with educators and local community members to construct the better democracy that our country both needs and deserves. Rather than exhorting young people to understand a staid conceptualization that reduces their own agency in the ever-changing American narrative, there is an opportunity for schools to engage our young people as legitimate political actors.

We can transform schools into crucibles of democracy by enabling them to center education in the communities in which they are located, construct classes that are relevant to students’ lives, and create a holistic democratic school culture.

This new vision of our schools begins with a greater respect for the local community in which schools are situated. Students need to understand that the community is a place where citizens make their wants and needs known and work together to solve communal challenges. Community members need to see the success of young people as relevant to the success of the community. Elected officials can learn to recognize students as purveyors of important local civic knowledge, capable of informing the most complex policy debates. Young people then have a real place in the community’s discourse and action.

As an example, GC students in New York City recently lobbied the city to build memorials dedicated to African American abolitionists. The students studied historical movements, noted the lack of representation in monuments throughout the city, and met with the mayor’s office to plot next steps. An education that focused on Action Civics allowed them to experience citizenship in their community while also studying the history of the abolitionist movement.

As a result, the students were excited. Education and democracy were not abstract. They were real concepts they were helping to mold, shape, and change.

This focus on the community also allows classes to become relevant and intersectional. Math transforms into a meaningful subject as students analyze traffic patterns and determine the ramifications of the local tax bond structure. English class involves analyzing articles in the local paper and learning persuasive communication skills through debating the merits of local policy.

Beyond classes, the school itself can fully embrace the community by becoming a place where students cocreate a culture that invites and nurtures their participation and that reflects the principles of democracy. In this type of school, students find meaning in education and become the producers and creators a democracy requires.

Too often, in our current day and age, schools and democracy are seen as boring and conventional, only telling young people what to do rather than inviting them in and listening to their concerns. By transforming schools into laboratories of democracy, and seeing students as real political actors, we can make school relevant, and even fun. And we can ensure that our education system returns to a focus that has oft been articulated but never totally reached: a public institution that molds and cultivates the next generation of citizens.

We need to bring civics back. Not just as a class in schools, but as the entire organizing principle into how our education system is structured.

2. Lower the Voting Age to 16

More and better comprehensive civics education is necessary. So is giving young people real ways to participate in the political process, starting now.

As we’ve discussed, the United States lowered the voting age to eighteen from twenty-one in 1971 after a decades-long fight to extend suffrage. The final, enduring argument was that if our young people were old enough to go off to battle, they should be able to vote for the elected representatives who were making the decision to go to war. The fight was led by young people.

New times call for new arguments — and a lower voting age.

Right now, with a democracy that is indisputably not working for young people, we need to offer young people the opportunity to fix our politics by lowering the voting age.

This idea almost immediately draws eye rolls when I first bring it up.

“Sixteen-year-olds? Voting? Give me a break. They can barely tie their shoes. And they’re eating Tide pods. Why would we let them vote?” I hear versions of this argument whenever I trot out this idea from, well, older voters.

“In any case, they’d be liberal anyway. This is just a reform to create more Democrats,” is another rebuttal I often hear.

This gut-instinct responses are logical, to an extent. Sixteen can seem young.

But when you witness the activism of the young people in Parkland, and acknowledge the fact that every single time we see change in this country, young people are at the forefront, you begin to see that sixteen-year-olds can be knowledgeable and effective. Almost every young person profiled in this book began his or her political activism before he or she turned eighteen.

Additionally, on the aggregate, young people are registering as independents much more than they are becoming Democrats and Republicans. This is not about creating more liberal voters. It’s about enabling and educating more informed voters, period.

We need to overcome our paternalistic instincts that tell us these young people are too immature to have informed political opinions. On the contrary, they might be the best hope for us to improve our democracy.

Chiefly and crucially, if we were to lower the voting age to sixteen, schools would be incentivized to teach more and better civics education. If students could vote for local officials while they were still in school, the relevancy of civics classes would immediately be apparent. Democracy, as taught, would no longer be abstract, but rather a concrete idea in which students could immediately put their knowledge into practice. We don’t learn to drive without being able to practice. Similarly, teaching civics while sixteen- and seventeen-year olds could vote would allow them to participate in our democracy in real time.

This idea is not new, and, like so many effective democratic reforms, it is not just American. Other countries, from Finland and Scotland to Argentina and Ecuador, already allow sixteen-year-olds to vote, and they see higher rates of participation among their youngest populations than we do in the United States. Additionally, numerous cities across the country, including Takoma Park and Hyattsville, Maryland, currently permit sixteen-year-olds to vote in local elections. This is not a radical reform. Rather, it is a necessary one given the state of our current democracy.

Voting Is a Habit — Start It Young

One of the arguments made against lowering the voting age is that young people don’t currently vote at high levels. Why should we lower the voting age if eighteen-years-olds aren’t even voting?

In reality, eighteen is a pretty terrible age to start enabling young people to go to the polls. Most young people are either in college or in the workforce for the first time; they are not thinking about their first election. Additionally, if young people are in college, outside of their home community or state, the laws about voter registration can be arcane and challenging to follow. At times, states have implemented explicit regulations to discourage young people from voting: some states have passed laws requiring eighteen-year-olds to register and vote in their home districts, even when they are off at college.

The idea that eighteen is not the ideal age to start the voting process is not just anecdotal. The overall voting rate has decreased steadily since the age was lowered in 1971, suggesting that voters are missing their first election and then unfortunately are establishing missing elections as a habit.

Allowing sixteen-year-olds to vote would ensure that young people are able to vote while they are still in school and living in their communities. Young people are more likely to vote in a more stable environment, in a community they have always known as home. Schools and parents alike could work to ensure that young people are aware of upcoming elections, educated on the issues, and are actually showing up and participating.

This is not just a theoretical argument. Statistics from countries and communities that have lowered the voting age indicate that sixteen-year-olds are far more likely to vote than eighteen-year-olds. In Takoma Park, Maryland, in the 2013 election (the first in which sixteen-year-olds could vote), the turnout rate for registered sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds far exceeded any other demographic.

Evidence from Europe is also positive. Austria lowered its voting age to sixteen for all of the country’s elections in 2008, and turnout among that age group has been higher than for older first-time voters. In the 2011 local elections in Norway, twenty-one municipalities used a voting age of sixteen as a trial and found that turnout was also much higher than turnout among older first-time voters.

Just like any habit, individuals are more likely to continue the practice if they start it young. When eighteen-year-olds do not vote in their first election, because they are preoccupied with college or the workforce, they are significantly less likely to vote in subsequent elections.

By the same token, if young people do vote in their first election, they are significantly more likely to vote in all subsequent elections. Research indicates that voting in one election can increase the probability that a voter will participate in the next election by 50 percent.

It is this argument that serves as a rebuttal to the notion that lowering the voting age is a partisan campaign. All Americans should want a democracy in which more people participate — it will lead to more representative policies. Desiring a more robust, representative democracy with more holistic participation, especially in local elections, is not a partisan sentiment — it is an American one.

We are currently witnessing historically low voting rates across the country, especially in local elections (with an average rate hovering around 25 percent turnout). Lowering the voting age to sixteen would be an innovative, proven way to begin to rebuild an engaged electorate.

Young People Have the Capacity to Make Informed Political Decisions

Core to any argument against lowering the voting age is the myth that sixteen-year-olds do not have the political acumen to make informed decisions.

“You trust them with our country’s future? I barely trust them to take out the trash,” some parents have told me.

“They’ll just follow their parents’ decisions anyway: they won’t make their own informed choices,” goes another oft-heard argument.

The statistics don’t back this up. Using the development of the brain’s frontal cortex as a barometer, sixteen-year-olds have the same ability to process information and make decisions as twenty-one-year-olds. Additionally, research demonstrates that sixteen-year-olds possess the same level of civic knowledge as older young adults, and they also demonstrate equal levels of self-reported political skill and political efficacy of older adults.

Yes, there will inevitably be some young voters who go to the ballot box uninformed or who simply vote the way that others tell them to. But how is that reality different from regular voters? Just as there may be uninformed young voters, there are uninformed older voters.

Sixteen-year-olds do have the ability to make smart decisions. We just need to let them show up.

Our Youth Deserve the Right to Vote

Today, a sixteen-year-old can get a job, work hours without significant restrictions, pay taxes, and get behind the wheel of a car without any adult supervision. They deserve the right to have a say in the political issues that affect them on an everyday basis. Allowing them to work and pay taxes without an actual vote is equivalent to taxation without representation.

Additionally, young people feel challenges in their community the most acutely. They are directly impacted by changes in education funding, school board decisions, jobs initiatives, police programs, and public works projects. And, like the students in Parkland realized, gun violence affects our nation’s schools, and young people, in disproportional and tragic ways.

Our tendency to look to the political issues of the moment, rather than the foundational challenges that face our future democracy, is an abdication of our responsibility to take care of our young people. We, as adults, have clearly not solved or made substantial progress on so many issues that affect our youngest generations. We should enlist young people as equals to help us solve our problems.

We need innovative ideas to spur political participation. Young people have the ability and acumen to make informed political decisions. And they deserve the right to have a say in issues that affect them. Lowering the voting age is not a ridiculous idea. It’s a commonsense reform whose time is rapidly coming.

If we are serious about speaking truth to power and acknowledging the reality that young people always lead us forward, we need to lower the voting age to sixteen.

3. Put Equity at the Forefront

We need to ensure that we are creating a democracy that increasingly places equity at the forefront. And specifically, racial equity. Young people can help achieve this goal of ensuring that every single young person, irrespective of their background, can have a real voice and say in our country’s future.

In our current lexicon, diversity, equity, and inclusion work has become increasingly important, with reason. But oftentimes, we do not actually dig into the definition of those three terms.

Diversity is quite literally the presence of difference within a given setting. You can have a diversity of opinions, a diversity of clothing brands in a closet, or a diversity of experiences on a team.

Inclusion refers to the diversity actually feeling integrated, valued, and leveraged within a given setting. In a team context, this means that the diversity of experiences, culture, and opinions is actually valued, rather than solely being present.

Equity is the process that ensures that everyone has access to the same opportunities. This is not equality, in which everyone literally has the same material goods. Rather, equity recognizes that inherent advantages and barriers are already in place that either promote or impede success. In our democracy’s case, being white has led to certain ingrained advantages, especially because of the manner in which our very country was created. Recognizing the unequal starting place that our democracy has created, equity works to correct the imbalance.

In a new twenty-first-century democracy, the goal of equity must be front and center in any effort. We must recognize that the playing field is fundamentally unbalanced. When I started Generation Citizen, I did everything I could to ensure the organization succeeded. I had my fair share of challenges. But I also started with an inherent advantage — I was a white male with an Ivy League degree. Many of our original supporters were Brown University alumni, and I had instant credibility when I walked into certain rooms because of my appearance and my pedigrees. That intrinsically is not equitable. Thus, a principle goal of any democratic practice needs to be ensuring that diverse matters are included and valued toward an end goal of equity.

This reality stems from two related truths.

First, our democracy continues to value certain voices over others. This is the result of being a country founded by white men that has labored under a patriarchal social system.

And second, our democracy looks, and will continue to look, a lot different than it ever has. In 2014, children of color became the new majority in the United States’ public schools. Demographers predict that whites will make up less than half of the country’s population by 2044, if not before. We’d be wise to put racial equity front and center now — not as a by-product of democracy, but a component of the process absolutely necessary in the ideal’s next iteration.

Listen to our young people

As we focus on ways that young people can take their own political journeys, we need to put reforms in place that encourage and sustain active and equitable youth voices. We’ve seen throughout this book that young people have always been at the forefront of change in this country. To reach a better political future, young people need to lead us. But there are structural changes we can enact to help young people lead.

Lowering the voting age, ensuring schools are harbingers of democracy, and putting equity at the forefront are three critical ways that we can ensure that every young person can lead his or her own powerful political journey.

Politics doesn’t have to suck. Our democracy can still work.

But only if we put young people at the center. And we help them get there

Copyright 2019 by Scott Warren, from Generation Citizen: The Power of Youth in Our Politics. Excerpted by permission of Counterpoint Press. (Buy the book)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)