From Voters to Donors, Education Emerging as Key Issue in California’s Gubernatorial Primary; While Newsom Leads, Cox & Villaraigosa Fight for 2nd

This article was produced in partnership with LA School Report

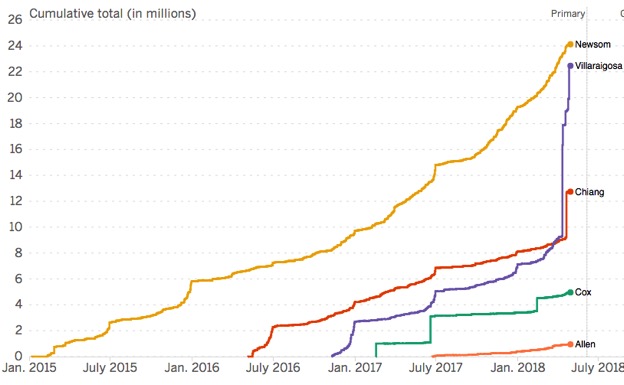

In February 2015, barely three months after he was elected to a second term as California’s lieutenant governor, Gavin Newsom announced he would run for governor in 2018. The onetime mayor of San Francisco, where his dash and early support of gay marriage made him a high-profile hero on the left, raised millions for his campaign long before another candidate entered the race.

He has never trailed, and he will likely remain the front-runner heading into next month’s “jungle” primary, which will send the two top vote getters, regardless of party, into November’s general election. Much of the race’s drama is unfolding in a close contest for the second spot and the right to challenge Newsom for leadership of an economy larger than all but four countries and a heavily Democratic-voting population.

Republican John Cox, a Southern California businessman who has run for office several times unsuccessfully, appeared to move a few points ahead of former Los Angeles mayor and past state Assembly speaker Antonio Villaraigosa in April, though polling results were uneven.

The state’s major newspapers split their recommendations between the top two Democrats. On May 9, the San Francisco Chronicle endorsed Newsom, and a day later, the Los Angeles Times urged voters to support Villaraigosa in the June 5 primary. The Mercury News and The Sacramento Bee also backed Newsom, while The San Diego Union-Tribune favored Villaraigosa.

Under Gov. Jerry Brown, who twice served two terms as governor and at age 80 is reaching the end of his term limit, California became a bulwark against Trump administration policies on health care, climate change, and, particularly, immigration. In March, the Department of Justice sued the state for protecting undocumented immigrants from deportation. The president is viewed less favorably in California — his approval rating is 31 percent, and just 16 percent among voters under 30 — than nearly anywhere else, and his polarizing presence has imbued the governor’s race.

“This is not just California but everywhere: Trump just dominates everything,” said Larry Grisolano, a consultant who is working with a super PAC supporting Newsom. “How candidates project and juxtapose next to Trump is a necessity, and especially among Democrats, because that’s who’s most energized at the moment.”

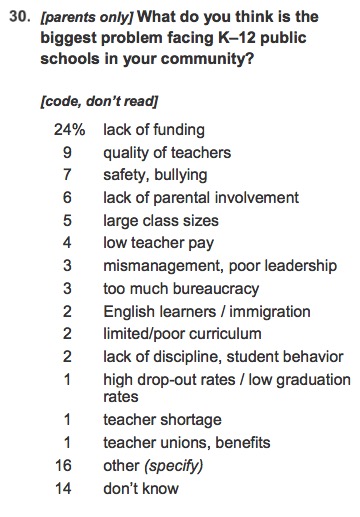

In a March survey, the Public Policy Institute of California found that, along with hot-button issues like immigration and gun and school safety, education is a top concern for the state’s voters, with 64 percent saying the candidates’ positions on K-12 issues were “very important” — a sentiment that crossed party lines but was more common among Democrats (69 percent) than Republicans (55 percent). Another 26 percent said the issues were “somewhat important.”

“People may say they’re going to be the ‘education governor,’ but in California every governor is going to be the education governor.”

—Mark Baldassare, president and CEO, Public Policy Institute of California

Sixty percent of voters told the policy institute in a subsequent poll that state funding for schools was inadequate, and a majority (61 percent) said they favored amending Proposition 13 of the state constitution, which limits local property taxes, so that schools would receive more money.

“People may say they’re going to be the ‘education governor,’ but in California every governor is going to be the education governor,” said Mark Baldassare, the institute’s president and CEO. “In California, so much of the funding in our 40-year, post–Proposition 13 world is driven not by local funding but by state funding. That for so many voters is what the government is about: taking care of schools.”

On Education

The flow of dollars from powerful interests has put education near the center of the campaign and possibly exaggerated differences between some of the candidates. Newsom, who is supported by between 21 percent and 30 percent of voters, won the backing of the powerful California Teachers Association last fall. But the gap between his platform and the platform of Villaraigosa, his closest Democratic rival, was more about tone than substance: Both emphasized early education and child welfare, increased school funding, and better access to college.

Newsom has stressed community schools, which provide basic health care and other services to disadvantaged students and their families, while Villaraigosa wants to increase teacher pay and training.

A policy rift opened in February when Newsom’s spokesman told The Sacramento Bee that the candidate, a past charter school supporter, had indicated to the CTA while aiming for its endorsement that he was against expanding charters in California “until there is real oversight and stricter enforcement,” the spokesman said.

It’s unclear that Newsom’s concession was necessary. Villaraigosa’s support for a legal challenge to state tenure laws, and his accusation that teachers unions blocked change while he was mayor, made the former Los Angeles union organizer a pariah to his old union, and to the statewide CTA, years ago.

But the unions’ resistance to his agenda while he was mayor also elevated his stature in the school reform movement. His April polling numbers seemed stuck somewhere between 9 percent and 18 percent of voters, but he was expected to get a big boost after deep-pocketed charter supporters donated $12.5 million to an independent expenditure committee supporting his candidacy. Reed Hastings, the Netflix CEO, led the surge with a $7 million contribution, while billionaire education activist and philanthropist Eli Broad and former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg also made seven-digit gifts.

“Villaraigosa has a record and history of making education front and center and charter schools being part of that vision,” said Gary Borden, senior vice president of civic affairs at the California Charter Schools Associations, which runs the super PAC supporting Villaraigosa. “None of the other candidates has made education front and center.”

With a war chest up to $22.5 million, Villaraigosa still has less to spend than Newsom, who has raised $26.5 million, but the new funds make him competitive across the state’s far-flung and demographically varying media markets, and observers expect a storm of advertising in coming weeks.

The ads will inevitably draw stark contrasts, but even as Newsom’s education record has been more pragmatic and centrist than he and many of his supporters acknowledge, Villaraigosa is not a stereotypical reformer.

Neonatal care and housing insecurity aren’t usually shortlisted priorities for market-driven education advocates, even in blue states, nor is a nostalgia for the arts that almost sounds like anti-reform champion Diane Ravitch.

“If there was one curriculum change, I’d bring back the arts,” Villaraigosa said at a March candidate forum. “You know, when I was a kid in the public school, you could play the trumpet for 25 cents and if you couldn’t afford it they’d give it to you for free,” he said.

“As we know, not everybody focuses on science and math — it’s a great way to learn science and math, by the way. Or social studies.”

The CTA doesn’t see similarities between the candidates, however.

“Villaraigosa is backed by corporate billionaires with a privatization agenda and one that takes funds away from neighborhood public schools and moves to those privately run charters,” said CTA spokeswoman Claudia Briggs. “Newsom believes teachers are the solution to public education issues, where Villaraigosa wants to take away the professional rights of educators.”

Several of the gubernatorial candidates will participate in “Building Our Future: A Forum on Children” May 15 from 6 to 8 p.m. at the Los Angeles Trade Technical College. The event is open to the public and co-hosted by The Chronicle of Social Change, the Children’s Defense Fund–California, and the Children’s Partnership in partnership with LA School Report, The 74’s sister site, and the Los Angeles Daily News.

Republican Challenge

Either Democrat would be preferable for teachers unions to Cox, the affluent businessman who is clocking a few points ahead of Villaraigosa (and who once ran against Barack Obama for a U.S. Senate seat in Illinois). Cox caught heat by not voting for Trump, but, like other Republican office seekers nationally, he has aligned his views with the president’s. In California that means opposing the state’s support for immigrants, defending gun rights and the Proposition 13 property tax ceiling, and repealing a gas tax passed by Brown.

Cox’s ideas on education are underdeveloped but echo Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s calls for more parent choice and making schools compete for students. At a March education forum he decried tenure (“I can be fired at any time. And you know what, it makes me better”), opposed free tuition at state universities, advocated for civics education, and argued that money doesn’t improve schools.

“Competition is the only way to get quality and efficiency,” he said. “Every day I wake up in the private sector and I try to do something to beat my competition.”

Cox faces large but not insuperable obstacles to making it through the primary successfully. The state Republican party is weak: only a quarter of voters are Republican, and no Republican has won statewide office since 2006. State GOP officials failed to endorse either Cox or state Assemblyman Travis Allen, an unabashed Trump supporter who trails Cox by a few points, preventing either from ascending as the consensus candidate among state conservatives.

Cox will also need Villaraigosa to fall back, perhaps losing some of his support to John Chiang, an early favorite among state workers and Democratic party regulars whose candidacy has failed to ignite. California’s treasurer and former controller, Chiang has deep support among Asians and is well funded, but he has attracted only single-digit support.

A former state education superintendent, Delaine Eastin, trails the other Democrats.

If Cox fails to finish in the top two, the race may have unusual national influence. Republican leaders in the state worry that the absence of a Republican at the top of the ticket in November will depress turnout among GOP voters. With a half-dozen vulnerable Republicans in congressional elections, according to a Yahoo News analysis, the result could affect the control of Congress.

A race between the two Democrats would be more competitive than if either ran against Cox or Allen.

“A Republican would be ideal in the general election,” Newsom joked at a debate last week. “Either of these two will do.”

A final turn of the screw: Traditional polling places no longer exist in five California counties, where residents were mailed ballots and were able to vote in the June 5 primary beginning last Monday, May 7.

“I’m guessing that three-quarters of the ballots will be in by Election Day” in these counties, said pollster Mark DiCamillo.

Disclosure: The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies provide financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)