74 Interview: Morgan State’s Daryl Scott on Ron DeSantis, White Guilt and How Florida’s AP Clash is ‘Erasing History’

The historian said that the need to preserve large markets like Florida means “the College Board was always going to cave” on African American Studies

By Kevin Mahnken | February 23, 2023The showdown in Florida between Ron DeSantis and the College Board shows no sign of abating.

After his administration prohibited the adoption of a newly developed AP course on African American studies, the Republican governor went even further last week, openly musing about dropping all AP classes throughout the state. Even with many Florida students and families protesting the decision, governors in four other states have announced that they would also review the content of the new course, warning that it could introduce political content into classrooms.

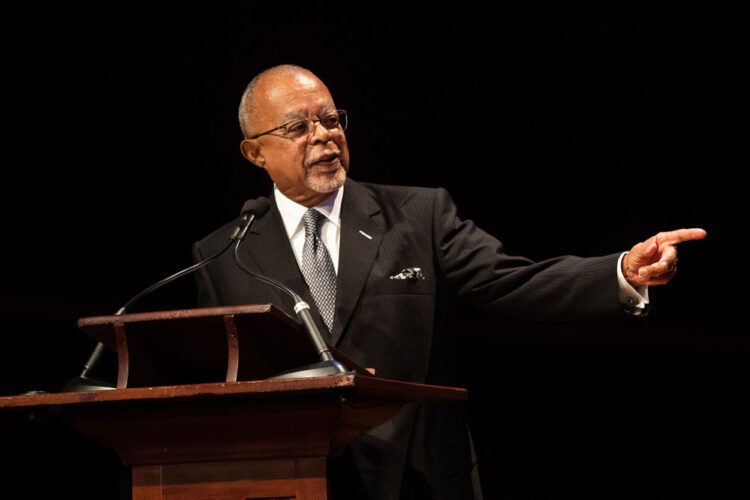

Daryl Scott, a professor at Baltimore’s Morgan State University and self-described “anti-public intellectual,” sees enough blame to go around. While lacerating the College Board for acquiescing to DeSantis’s criticism and revising its product, he sees the rising GOP star as an opportunist exploiting white anxieties to build his political brand.

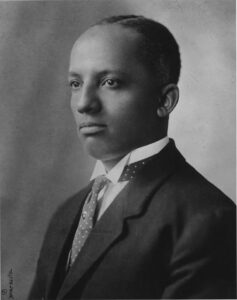

Scott spent much of his career at Howard University before departing to chair Morgan State’s history department last year. He previously served as the president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, which was founded in 1915 by the pioneering Black thinker and academic Carter G. Woodson. Along the way, he has become a kind of historian of Black studies, acquiring an insider’s view of the field’s leading figures and intellectual tendencies: multiculturalists and Afrocentrics, social scientists and humanists.

His commentary on national affairs and Black historiography bleeds over from his published work to a lively social media presence. In neither venue is Scott known for pulling punches, sometimes excoriating writers and educators for yoking their scholarship to political causes. Over the last few years, one of his most frequent targets has been the New York Times’s 1619 Project, which he recently critiqued as “an exercise in African American exceptionalism that elides the question of class.”

In a conversation with The 74’s Kevin Mahnken, Scott turned his focus to the political clash in Florida, where he said conservative backlash is endangering the study of Black history. But he added that historians and teachers alike should be leery of wading into cultural wars that they aren’t equipped to win — and potentially alienating families in the bargain.

“We need to take seriously that white mothers do not want their kids to have their psyches toyed with in K–12, and we can’t tell those mothers to just have their kids toughen up,” he said. “If we’re going to counter this onslaught, we need to take that opposition seriously and find ways to take away their criticisms.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Let’s talk about the content of this AP course. The critique from the Right is that the curriculum, and particularly the sections that focus on more recent history, privileges radical voices and leftist critiques of American society. Do you think there’s substance to that complaint?

Daryl Scott: I’m pretty much a gadfly when it comes to that final curriculum. It’s not so much that I take issue with it. I just want to point out to the people who participated in it that it could have been a much different curriculum.

First and foremost, it’s a college course that’s taught in high schools. This is where some folks on the Right get lost, but again: This is a college course, taught in high schools, potentially for college credit. And it becomes the basis for admission into the better colleges in this country.

I happen to have been part of the redesign of AP U.S. History, which recognized a whole lot of things that the Right now calls problematic. So maybe we should just stop for a second to see what they’re calling problematic. Half of critical race theory has to do with optimism versus pessimism about the present and future of race in America. The pessimism started in the 1950s, with people like Derrick Bell saying that things weren’t going fast enough: “These obstacles are here! We thought we were going to dismantle the structure of white supremacy and usher in equality, and it didn’t happen. Will it ever happen? Maybe not.”

When did pessimism become something you can legislate against? We’re legislating against pessimism now, and legislating for American exceptionalism? And as I’ve said elsewhere about the 1619 Project, when did racial progress become a pet idea of conservatives? I’m old enough to remember — and we should still have to teach — that it was conservatives who believed Black people couldn’t assimilate; now they’re saying they’re optimistic that Black people should assimilate, and you can’t teach otherwise.

The big point is that academic freedom in a college-level course dictates that we can debate all these things. This is why they’re fundamentally wrong, no matter what’s in the College Board’s curriculum. And this is why the College Board itself was fundamentally wrong when it allowed itself, whether through external pressure or otherwise, to be put in what I used to call “self-check.” If they weren’t being expressly censored by the state of Florida, they self-censored. And they did this for the same reason textbook publishers do it all the time: so they could get their products through state departments of education. That has a negative impact on what is being taught.

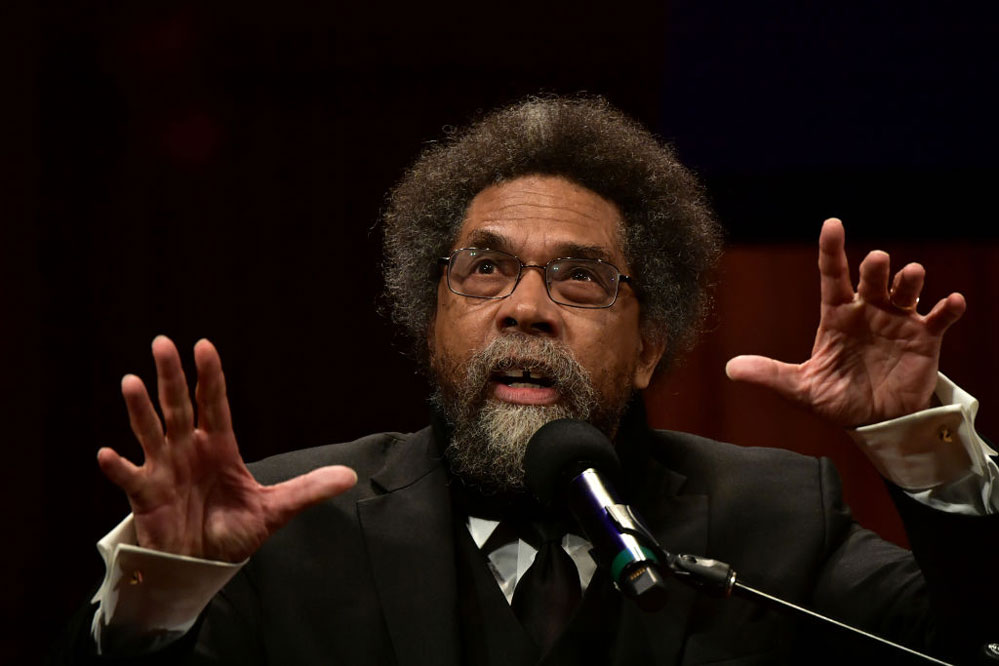

We’re saying that we’re going to create a college course for high school students, and we’re going to limit inquiry? Can we get more backwards and un-American than that? My belief system has always been one of racial pessimism, and here’s what I mean: I’ve been of the belief that the best we could do as a society was to hold racism in check. And we could reach a set of fairly equal opportunities, and likely equal outcomes, if we could hold racism in abeyance. That marks me as a pessimist; in Black studies, there are lots of people who call themselves Afropessimists, and there are critics of Afropessimism, like Cornel West, who now has to defend pessimism [against censorship]. I don’t want to speak for him, but West used to argue that the problem with racial pessimism was that it didn’t believe in the Christian notion of human progress and redemption.

“By labeling everything ‘critical race theory,’ it brings out three things conservatives don’t like to hear: They don’t like ‘critical,’ they don’t like ‘race,’ and they don’t like ‘theory.’ Critical race theory has become the perfect foil to go after everything you don’t like in a history culture war. So it’s brilliant on their part.”

Some people say, “Well, you can’t teach about Black Lives Matter,” but at this point, something that happened between 2013 and 2020 is pretty much a historical topic. If you can’t even teach about the facts of that movement, you’re doing something that used to be done in the Soviet Union — erasing history, saying, “That is not a valid topic of inquiry.” Black studies includes debates around reparations, and anyone who follows my work knows I don’t think reparations are going anywhere. But in a democracy, reparations can be debated.

One of the problems with the whole course is that it attempts to be a history course. But Black studies, and many studies, tend to be fairly contemporary. The content of most of these courses, if you were to ask me, should be 21st-century topics. We should be trying to figure out the consequences of assault weapons through these courses, the consequences of a society in which quality healthcare is not widespread. In other words, the need for a studies program at the college level is to be robust in debating the issues before society. What we’re being told in Black studies now is that we can’t debate things because it’s indoctrination, and yet, the people claiming this say that we should be teaching American exceptionalism. That’s an indoctrination program.

The concern of everyone in a democracy should be how we debate matters, not what we debate. Some people on the Right have reached the foregone conclusion that we’re not going to have a debate and that teachers will, of necessity, indoctrinate. They’re pretending that we’ve got madrassas out here. But nobody’s sending their kids to madrassas, and anybody who understands the teaching profession knows that they try their best not to indoctrinate. So no matter what critique I have of the content of the College Board course — and I do have a critique — the bigger issue in a democracy is academic freedom and holding teachers responsible for teaching responsibly. If they’re indoctrinating, it should be dealt with in schools, not at the state level.

You mention a few times that the AP African American Studies course is effectively a college seminar. But it’s still being taught to high schoolers, and academic freedom is strictly limited, if not nonexistent, in K–12 settings. If 16- and 17-year-olds are being taught a curriculum that Florida voters don’t agree with, doesn’t the governor have the authority to intervene?

I hear what you’re saying. But let’s put brackets around the College Board, because we know that the origins of Florida’s law [the Stop WOKE Act, passed in 2022] don’t lie with the College Board. The origins lie in the broader assault that comes in the wake of, and as a consequence of, the New York Times’s 1619 Project.

Some genius of political persuasion put three words together that are very volatile: critical race theory. It never gets taught like that in K–12 settings, but I’m a good enough intellectual historian to know that nothing stays within its box. So elements of it have been taught in K–12, and the power of this critique is right in the name. By labeling everything “critical race theory,” it brings out three things conservatives don’t like to hear: They don’t like “critical,” they don’t like “race,” and they don’t like “theory.” Critical race theory has become the perfect foil to go after everything you don’t like in a history culture war. So it’s brilliant on their part.

The problem is that they’re effectively telling parents — Black parents, white parents, any parents — that their children cannot be taught Black history if it’s not a good-time story. To survive under this repressive regime, Black history has to shoot for [a tone] somewhere between the old-school, “We all happy negroes here,” and this other idea, “Ain’t we done great lately?” That’s the content they’re allowing to be taught, and anything else is said to be something that makes whites feel guilty.

Now, I do hear what you’re saying, and I keep telling people to stop acting like we’re talking exclusively about college courses. We should pause and ask the question, “Are white kids being made to feel bad about America? Are white kids being made to feel bad about being white? Are they being made to feel individually guilty for slavery or any other form of racial oppression?” To the extent that is the case, white parents have a point, and they have cause for concern — in the same way that Black parents, historically, had cause for concern that their children were being taught that slaves were happy and didn’t really want their civil rights, or were being told that they were racially inferior.

Everybody in a multicultural, multiracial democracy has a vested interest in their kids not being taught to have negative feelings about themselves. That should never be the goal of K–12 education. I’m not going to be flippant, like some of my colleagues can be, and say that white kids should just toughen up. No, we’re talking about kids! Everybody’s got ’em, and I don’t want to accept that an eight-year-old boy, or even a 15-year-old girl, should have to “toughen up.” The teacher is supposed to take care that generalizations are not visited upon individuals in a way that makes them responsible for what someone else has done. Children cannot bear the weight of all of society’s ills. We believe that self-image should not be damaged through the educational process. So to the extent that white parents have this concern, we all need to address it.

But that does not make it legitimate to go wholesale into violating what should be free inquiry. You should not reduce the curriculum to something resembling a right-wing madrassa. That is the problem with DeSantis: Rather than just saying that educators have the burden of delivering curriculum that leaves intact the self-image of all students — and most teachers do this — he is creating a fairytale effect for white folks at the expense of all students learning. And race is only one side of the [Stop WOKE] law. The real focus of that law is LGBTQ rights, because there’s a live debate about when these discussions enter education. We need to have that debate in a sane and civil way as well, but not by outlawing things at the state level and exploiting the politics to get elected.

“The notion that white kids were being made to feel bad was what flipped some people from Democrat to Republican. We need to take seriously that white mothers do not want their kids to have their psyches toyed with in K–12, and we can’t tell those mothers to just have their kids toughen up.”

It’s notable that this clash between Florida and the College Board just seems to keep growing. Gov. DeSantis has now said that he’s open to the state just dropping the whole range of AP courses.

It’s been suggested that the College Board should have told Florida, “Take ’em all or take none!” I’m not a political prognosticator, but it’s also been said that DeSantis stakes out hard positions that he later reverses when no one is looking. For example, he went after Disney, but then later took the teeth out of all the measures he was supporting. So this seems like a feint of some sort, because there would be hell to pay in Florida [if AP courses weren’t offered]. There are so many kids in Florida who need the AP courses to get to the best schools in the country.

You don’t just get college credit from the AP exams. Some schools use AP scores as a proxy to determine who’s qualified to attend. And politically, it’s not like Florida is Mississippi. People would be up in arms, whether it’s the well-heeled people or the striving people, about the prospect of their kids not having access to AP classes.

So the College Board might get the better of DeSantis on this, but to me, the College Board should have stood on principle rather than self-censoring. Or they should have had the guts to take a look at this stuff earlier on. In other words, they brought people together, and they were trying to legitimize a class that was going in a direction they were willing to go. If they felt it was going too far, they should have had the guts to stop it before that point. Sometimes, you can feel the College Board giving you the sense of how far they’re willing to go. Having sat on a board, I know that the board is sometimes going to protect the institution. If they were disposed to doing that, the College Board should have been protecting the institution before they ultimately did.

But once they went down this road, I really believe their decision to cave in to censorship was wrong, because it was a massive cave-in. I’ve kept telling people, “Don’t believe any of the spin they’re putting out.” You could see their spin about this, and the next thing you know, Florida releases the correspondence between them and the College Board. There was no smoking gun, but they had a clear sense all along. When the law passed, they didn’t need anybody to tell them. Between the first version of the curriculum and the second, there was that Stop WOKE law, and they must have known which way the wind was blowing.

Is it necessary that there be a widely available course for high schoolers on African American studies? And, if so, should the College Board be the ones to develop it?

Everybody is free to do what they want. I believe in an open market of education.

By the same token, another track for all of this could have been pursued by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. It could have been pursued as well by the National Council of Black Studies. But especially when we’re talking about red states and the CRT debate, one of the issues has been finding consensus about the content for any of these courses. Whoever first took the initiative would have to fight for some kind of market share; schools would probably only adopt your particular version if, and only if, they felt it would be widely adopted. So it was likely that the College Board would be the most successful at this.

But if you know how the College Board functions, you’d know that their process was going to preserve the hierarchy of the academy. They were going to the most elite echelons of the academy and select participants from a cross-section of the discipline. It’s a multicultural strain of African American studies that I tie to the rise of [Harvard professor] Henry Louis Gates; he adopted the field as his own, as a department, as opposed to various programs that had a menagerie of people from different disciplines.

Something else has happened since then, which I call “Black Studies 4.0,” and which goes beyond what Gates and his generation of scholars signed onto. It’s a development out of the same camp, but it’s a more forthrightly race-conscious group. So it’s not surprising to me that elements of the AP course are different from what most of Gates’s generation would have created. Even though the College Board selected people like [Harvard historian] Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham and Gates himself to be figureheads of sorts, the content looks more like that of a younger generation. They’re in the same multicultural tradition, but this new generation is more race-conscious, more committed to tangible goals like reparations and LGBTQ rights and things like that.

This was always going to be an issue. For instance, in the College Board’s original curriculum guide, which was leaked, Afrocentric thinkers were just a marginal part of that. You’re not old enough to remember the ’90s, right?

Not really.

Well, this is where it gets interesting. People say that there’s been one continuous war against Black studies. But they’re kind of glossing over the 1990s and pretending that the political configuration is the same as it was then.

Here was the situation in the ’90s: Afrocentric scholars were placing an emphasis on changing the K–12 curriculum in many places across the country. They had great influence in the Black community and had some success in changing the curriculum to fit their goals. They got close to having great success in New York in changing the statewide curriculum and, in doing so, a political fight broke out between political liberals about things like Egyptology and about Afrocentrism. It was a fight about education, but it didn’t involve true conservatives; we’re talking about a fight between Afrocentrics — who often said that only Black people could study Black people — and mainstream academics, most often education policy people like Diane Ravitch. The way it played out, on the academic level, was as a debate over the claims of progressive and Afrocentric scholars that the Western tradition came “out of Africa.” I’m probably misrepresenting that clash somewhat because it was never my central concern in life. [Laughs.]

Can you provide a little flavor of how this debate came to be?

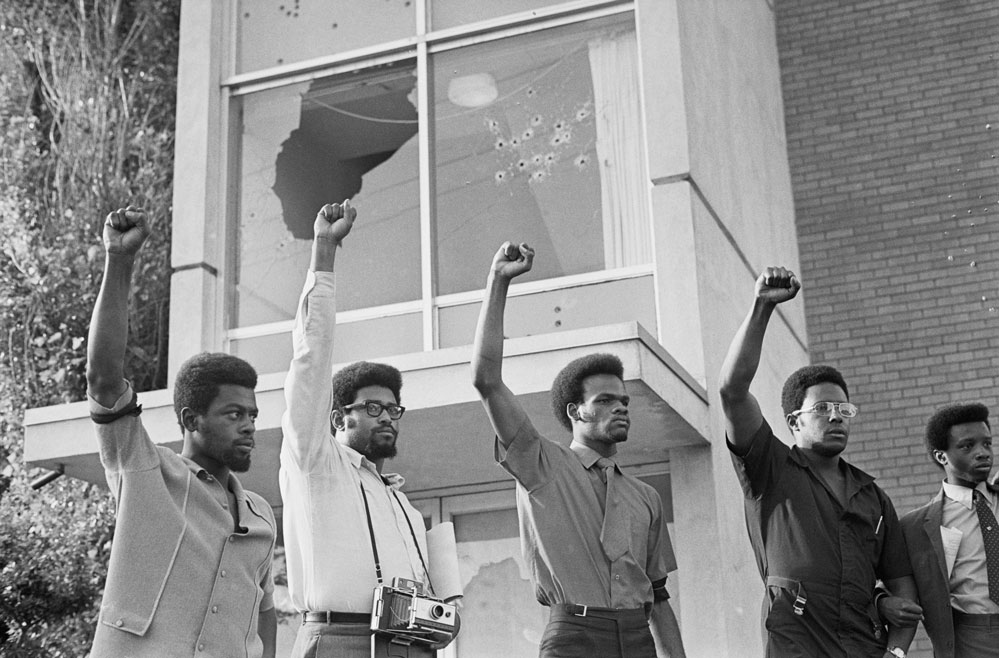

When Black studies came to higher education in the late ’60s and early ’70s, it was led by Black Power-ites, who tended to be social scientists and very political. They wanted policy changes, but they never succeeded in winning the mainstream of the academy. In fact, their affiliation with Black Power turned out to mean that Black studies only functioned well at the second and third tiers of the academy. In the elite schools, Black studies was pretty much a set of programs where people really stayed in their original disciplines. No one even conceptualized any notion of Black studies as having any kind of uniform mission. The Black Power-ites at the second- and third-tier institutions did.

They got slaughtered at the elite colleges, and most of the leading Black scholars wanted nothing to do with a departmental status for Black studies. The big-time Black scholars at elite schools were big-time within their own disciplines, not Black studies. I say all of this because Skip Gates finally moved from that programmatic style of Black studies at Yale to the creation of a proper Black studies department at Harvard, and how he got there was important: He got there by critiquing Afrocentrics. And he made the mainstream academy safe for a new brand of Black studies.

The point I’m making is that this fight in Florida isn’t just a new front in the same war. If you want to say this is the same war, you’re fooling yourself about who was fighting it all this time.

The conservatives weren’t in that fight! You can point to people like Allan Bloom and The Closing of the American Mind, or to [Arthur] Schlesinger’s book, The Disuniting of America. But remember that Schlesinger was an old-line liberal. Where we are now is a completely different place. Nobody back then was passing laws to invalidate the teaching of certain kinds of Black history. It’s a full-on assault on academic freedom, and it’s quite a different thing from last time.

It sounds as though you’re saying that the debate over how to teach African American history essentially has essentially broken through, from the academy to society at large, with predictable political effects. On the one hand, that’s potentially destructive, but on the other, it’s a marker of the success of the discipline, right?

It’s the success of a certain strand of Black studies, exactly. But there’s a related point: Before anybody ever talks about Black studies, and before it pops up as a field in the 1960s, there had been a Black history movement started by Carter G. Woodson in 1915. Over the years between 1915 and the 1970s and ’80s, what had effectively happened is that the study of Black history made it into the school systems. People like me never felt that it was enough, and I know the criticisms that said, “We only talk about the same five people every February,” but that was an exaggeration. It wasn’t a true assessment of the progress that was made in bringing the study of Black history into the curriculum.

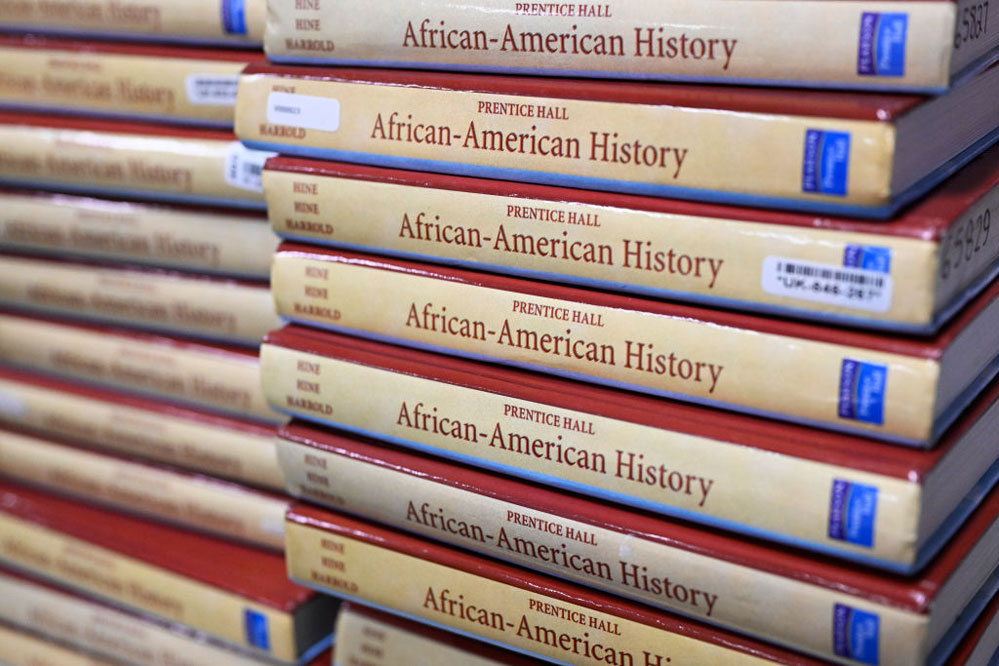

The Freedom Schools started during the 1960s. They included Black history. You saw textbooks changing to include Black subject matter and Black imagery. Hell, I’ve even seen books out of Bob Jones University Press that had multicultural images in them. In the ’60s, we were fighting a war for rights; but with that war came a notion that, now that Black people were in schools, they were going to be taught something about themselves. That’s how the rights war led to the culture war.

In the United States Army, I had officers who could stand up during Black History Month and lead pretty good Black history conversations. They knew the cast of characters. There was some kind of presence of it anywhere you went in society, even if you were talking about fairly conservative schools. In fact, I could take you to former segregation academies where they’re teaching Black history. The ones that survived did so because they were pretty upscale, and they ended up being integrated and hiring Black folks who would teach Black topics in courses. So let’s not pretend there was no progress being made, and let’s not pretend that conservatives were trying to purge it. Because they weren’t.

Given the existence of these laws about instruction on race and sexuality, what is the responsibility of organizations like the College Board when it comes to creating these curricula? I realize that they disappointed a lot of people by revising this course, but the legal reality in a large number of states meant that they were always likely to cave, right?

The College Board was always going to cave here, because they cannot afford to lose states like Florida and Texas. Even if they wanted to give up the “heartland,” they can’t lose those states.

Gates was attempting to create a multicultural democracy, and so he was more attuned to people’s feelings. This younger generation of scholars believe that you’ve got to power your way through. There is this sense that the ultimate victory is theirs, and sometimes, they don’t deal with the political realities of what won’t fly in the heartland, or off of college campuses generally. Quietly, there are people in the Black community who don’t want to hear that, and they’re not too interested in that kind of compromise.

I would have been much more open to debate within the confines of the College Board. But I become a hardcore advocate of academic freedom, particularly with a college course, once it’s been developed. And particularly when it’s supposed to represent the best knowledge we have, however we got to this position.

But I take the meaning of your question to be: If the College Board was going to cave, should they have been the vehicle for this project in the first place? I would flip it and ask, would anyone have adopted a Black history course from the Association of African American Life and History? Would it have been the gold standard at elite institutions?.

It’s like I said: Everybody is free to do what they want. Me trying to say what the College Board should or shouldn’t do would be akin to saying that McGraw-Hill shouldn’t have a Black history textbook. That violates the liberal principle, which I share with someone like Henry Louis Gates, that inquiry and the presentation of knowledge should be universal. In a democracy, you don’t have a monopoly on studying yourself and your own group; everybody gets a chance to put forward their version. So I support the College Board and its right to create this course. But as big a giant as it is, the fact that it caved is a bad thing for all of us.

Even with the disappointment you feel over the College Board’s reversal, I’m wondering how you feel about the development of a widely available course on African American studies. You may have designed it differently, but how do you feel about the end result?

Well, that is the shame of it all. There is no legitimacy to any course in African American studies that cannot grapple with the historic reality of the Black Lives Matter movement. Think about what it would be like if you said, “9/11 didn’t happen! Don’t talk about 9/11!” We can feel however we want about Black Lives Matter, but we can’t pretend that that movement — which has lasted for almost a decade — didn’t happen. Would you like for someone to say, “The ’60s didn’t happen”?

It’s beyond ahistorical. It’s erasing history and saying it didn’t happen. DeSantis wants us to say, so to speak, that Black Lives Matter did not happen. But Black Lives Matter has shaped much of the second and third decades of the 21st century. How do you pretend it didn’t happen, for good, bad, or ugly? Is the next thing to say that the LGBTQ rights movement didn’t happen? You can’t talk about it, so we can’t even study the historical phenomenon now?

The College Board will tell you, “You can do it, it’s an optional module.” But we know that optional modules aren’t tested and are rarely taught. Could you imagine a course on Western civilization where you can’t teach the French Revolution? [Laughs.]

What do you think of complaints that DeSantis’s win here was only partial — that the course still contains elements of left-wing orthodoxy that need to be expunged?

Here’s what I keep telling my friends when it comes to any of these related issues: We cannot write off the carnage that is already taking place, among both teachers and students, in places that aren’t just red states. There are cases in Oklahoma where teachers are being told they can’t teach Black history in predominantly Black schools, because they’re supposedly teaching it wrong. There was a case in Texas where CRT was used as a pretext to get rid of a principal.

So there is real carnage out here. The big losers are teachers and students. Now, the Left likes to say — and this is a lot of my colleagues — “Hey, we’re selling more books than ever!” Yeah, and that represents a fraction of the children who aren’t learning anything about topics that they were learning the day before yesterday. The impact of the anti-CRT, anti-critical analysis movement is profound. The National Review can pretend that every school district in any liberal state is teaching critical race theory, but you can get fired anywhere in Oklahoma because someone spies on your classes. So it becomes a way of going after people and purging Black history from schools in ways we’ve never really seen before.

“You should not reduce the curriculum to something resembling a right-wing madrassa.”

This hearkens back, as some have said, to the Jim Crow era, when Woodson’s disciples used to teach with his book under their desk at the risk of being fired. We won that war. It was a rights war that had cultural consequences. We win rights wars, conservatives win culture wars. But we’ve been fighting this thing as a culture war, and we’ve been so dumb and blind to not care about white kids as students. That’s the biggest mistake we’ve made.

When [Gov. Glenn] Youngkin won in Virginia, this issue of what kids were being taught was a big part of it. The notion that white kids were being made to feel bad was what flipped some people from Democrat to Republican. We need to take seriously that white mothers do not want their kids to have their psyches toyed with in K–12, and we can’t tell those mothers to just have their kids toughen up. If we’re going to counter this onslaught, we need to take that opposition seriously and find ways to take away their criticisms. It’s unethical for teachers to go after kids, and teachers typically don’t do it.

I saw a documentary last fall about how the Civil War is taught around the country. A teacher in a Boston school had a conservative kid in class. Even though he’s a conservative, I can identify a little with him: They went after him, and he held his ground. But the job of the teacher was to make sure that he had a chance to express his decidedly conservative point of view. The job of the teacher is to prevent the conversation from devolving into ad hominem attacks.

And when we go to even younger levels, teachers have an even greater burden. You don’t let kids gang up on anybody in those settings. That’s teaching, and that’s how we should discuss it — but to outlaw things is political demagoguery. And that’s where we find ourselves now, because we served up this culture war.

If you had a high school-aged child, would you let him or her take this AP class?

I would talk to my kid and let them make the decision.

My whole idea of parenting is to empower my kid to know how to make decisions, and then live with the consequences of what they decided. My kids are both grown now, but I don’t walk into a room and say, “Intellectually, you can’t do this for such-and-such a reason.” People have to be free, and this is part of it when we’re talking about high school-aged kids.

On the other hand, if I really thought my kids were being taught to hate themselves, or that they were guilty of something — oh hell, I’m getting into the school. Like I’ve said, we need to pay more attention to these parents. I think they’re being sold a bill of goods, but we shouldn’t just dismiss this with a sweep of the hand. “Toughen up?” You’re talking about kids who might be six or eight or 12 years old.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter