Exclusive: How Safe Are Philadelphia’s Schools? New Interactive Map Shows Discipline Reform Has Created a School Climate Catastrophe

Updated Jan. 19

Earlier this year, The 74 published a special series of maps compiled by Max Eden, all looking at the critical information contained in school climate surveys and mapping out responses to those surveys in the country’s two largest school districts — New York City and Los Angeles. (Click on the city names to see the maps, and read more about what Eden says he learned in surveying the safety data.) In this latest installment, Eden looks at school safety in Philadelphia based on surveys of students and teachers. NYC, LA, and Philly are among only a few large districts that conduct the surveys and make their results public. In a separate essay, Eden argues that all districts should do the same.

Several recently published studies paint a bleak picture of the effects of school discipline reform in Philadelphia. In the 2012–13 school year, the district banned suspensions for “conduct” infractions (i.e., classroom misbehavior). Studies by the University of Pennsylvania’s Matthew Steinberg and Mathematica’s Johanna Lacoe reveal that truancy skyrocketed, achievement plummeted, and, in a perverse twist, the racial suspension gap actually grew as African-American students spent more days suspended due to “serious” infractions.

Meanwhile, a qualitative study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Consortium for Policy Research in Education helps to explain why: These reforms have pitted teachers and principals against each other.

Still, discipline reform activists find such studies easy to dismiss. Maybe the deterioration was due to other factors. Maybe the schools are just experiencing growing pains, and given enough time will become better than before.

What are Philadelphia parents to make of all this? Studies by academics and counterarguments by activists can spark a much-needed debate, but ultimately, parents deserve to know what the students actually think.

Fortunately, Philadelphia is one of a handful of major districts that conduct school climate surveys and publish the results. Parents can go online and look at what students say, one school at a time.

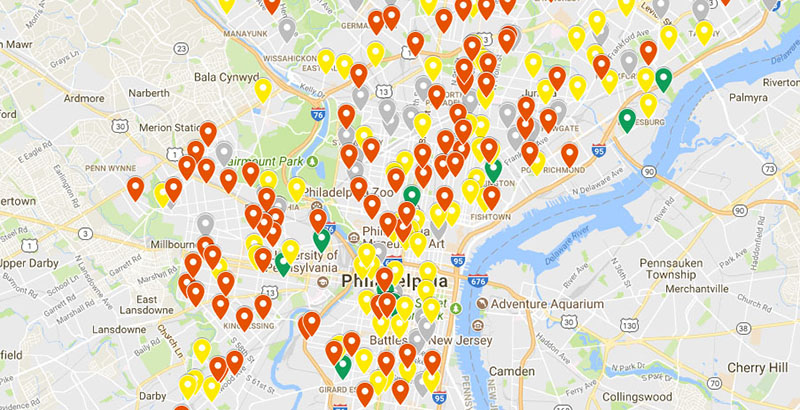

To make the data more broadly and intuitively accessible, my Manhattan Institute colleague Connor Harris and I pulled school climate data off the summary sheets of Philadelphia’s districtwide surveys to make it available on a Google map. For ease of navigation, I have color-coded schools based on the district’s Safety/Building Condition answer domain, which includes student responses to four questions about safety (safety in neighborhood, safety traveling to and from school, safety in school hallways, and safety in classrooms) and two questions about building condition (building in good condition, school clean). Per district practice, schools with fewer than half of students giving favorable answers are coded as “red” and “less safe”; schools with 50 to 75 percent of students giving favorable answers are coded as “yellow” and “somewhat safe”; schools with 75 percent or more of students giving favorable answers are coded as “green” and “safe.” Individual answers to all questions within these domains can be be found here but can be viewed only one school at a time.

A school climate catastrophe

Two things jump out.

The first is that there is a school climate catastrophe in Philadelphia. There are 119 schools where fewer than half the students give positive answers to safety questions; 101 schools where 50 to 74.9 percent of students give positive answers, and only 13 schools where more than three-quarters of students answer favorably.

When students are asked about a sense of belonging, the answers are also bleak. Fewer than half of students at 131 schools report a sense of belonging; 50 to 74.9 percent of students answer favorably at 100 schools, and more than three-quarters of students answer favorably at only one school (Widener Memorial, a specialized school for students with disabilities).

When it comes to maintaining a respectful environment, fewer than half of teachers at 73 schools report good news, 50 to 74.9 percent of teachers give positive answers at 154 schools, and more than 75 percent of teachers answer favorably at only five schools (all of which are charters).

The second thing that jumps out is that charter schools are generally safer than traditional district schools. There are 102 district schools and 16 charter schools that fall in the “red” zone; 68 district schools and 32 charters that fall in the “yellow” zone; and five district schools and eight charter schools that fall in the “green” zone. Fewer than half of teachers give a positive answer about student respect in eight out of 37 charters, compared with 65 out of 195 district schools. It’s worth noting that not all charter or district schools report student answers. We have no answers from students in 11 of 67 charter schools and 34 of 211 district schools.

For safer schools, trust teachers

What accounts for the charter edge amid this sea of schoolhouse disorder? Part of it could be attributable to differences in students. But part of it is undoubtedly due to differences in school culture.

The Consortium for Policy Research in Education study reveals that discipline reform has created a major rift between teachers and administrators. Despite years of being told that suspensions are useless or counterproductive, teachers still believe they work. More than 80 percent of teachers think suspensions are essential to send a message to parents about the seriousness of their child’s misbehavior, ensure a safe school environment, and encourage other students to follow the rules. About two-thirds of teachers believe that suspensions deter further student misbehavior.

But administrators think the teachers are wrong. And when the adults in a school aren’t on the same page, when teachers don’t believe that their principals have their backs, bad things are bound to happen.

According to the researchers, “Teachers and other non-administrative staff frequently described frustration with their administrators’ refusal to suspend students for what they regarded as serious or repeated offenses.”

The researchers quote one teacher who says, “We as teachers don’t really have a say-so in whether or not a child can be recommended for suspension. That’s an administrative decision that’s made without our input.” The researchers reflect that “examples like this, in which teachers reported feeling isolated and unsupported, or even directly undermined by administrators, came up frequently in our interviews and focus groups.”

Administrators are equally frustrated, particularly when not all teachers are on board. As one administrator tasked with implementing “positive” interventions said, “If we had consistency, I think the system would have a chance to work better. But things aren’t consistent, so I feel it’s kind of like banging your head against the wall.”

Although she and I have had our differences over school choice, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten has an eminently sensible stance on school discipline

Charter schools have the autonomy to ensure that all teachers and administrators are on the same page. Ideally, that’s how traditional public schools would operate as well. But discipline reform activists have undermined teacher authority by systematically second-guessing their judgment. Fundamentally, discipline reform is about not trusting teachers to do what’s right — about forcing them to give up what they think works in favor of an alternative they might not believe in.

It should, then, be little wonder that a policy that sows division between teachers and principals would also sow disorder within schools.

Although she and I have had our differences over school choice, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten has an eminently sensible stance on school discipline: “Safe and welcoming environments, clear codes that are equitably (not discriminatively) enforced are key — with resources that back it up. Not top-down mandates from superintendents or threats to teachers that if they report or take action they will be disciplined.”

Perhaps the reason that schools in Philadelphia are neither safe nor welcoming is that discipline reform’s top-down mandates have eroded clarity and consistency.

In this regard, Philadelphia is hardly unique. The Obama Department of Education issued “Dear Colleague” guidance threatening school districts with a federal civil rights investigation if they didn’t follow Philadelphia’s lead.

As scary as Philadelphia’s school climate data may be, what’s far scarier is that most everywhere else, parents are totally in the dark.

Max Eden is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, specializing in education policy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)