Despite Urgency, New National Tutoring Effort Could Take 6 Months to Ramp Up

With a third pandemic summer already here, one organizer admits, ‘There are …some lost opportunities’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

With a third pandemic summer underway, the Biden administration’s new push to recruit 250,000 tutors and mentors is getting a late start in helping students recover from academic and social-emotional setbacks. Organizers and experts say it could be 2023 before families and schools see the impact.

“We can’t mobilize fast enough,” said Robert Balfanz, an education professor running the new National Partnership for Student Success, housed at Johns Hopkins University. “There are still some lost opportunities.”

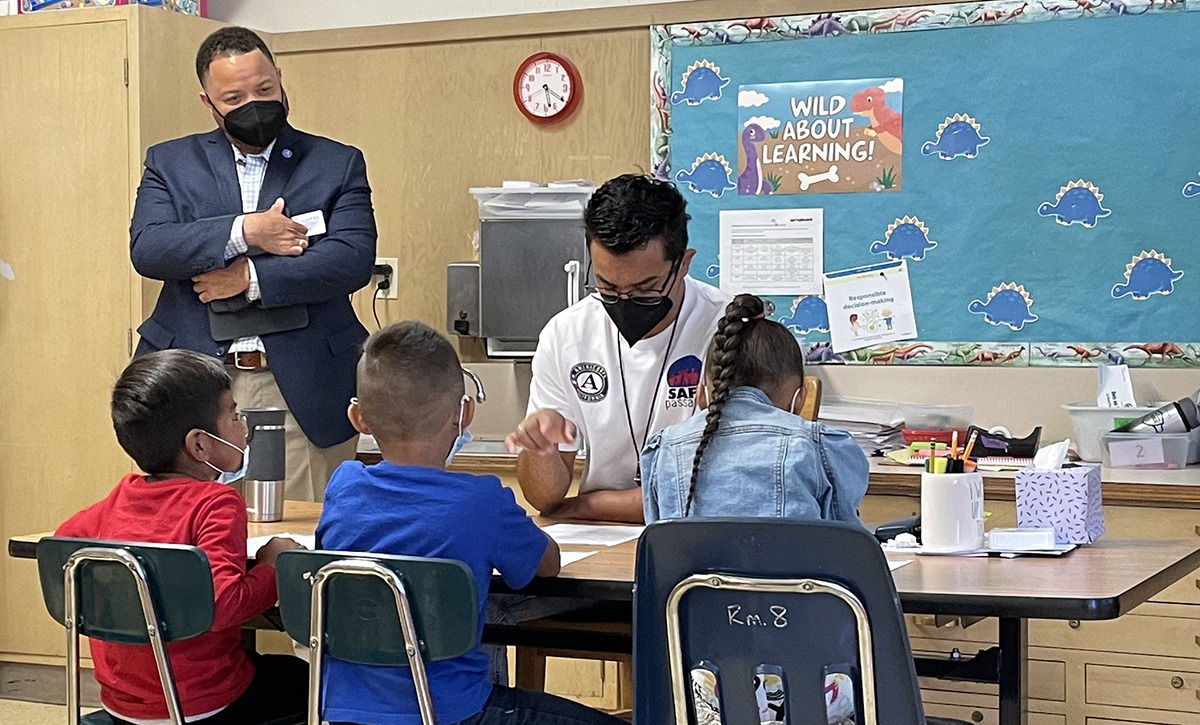

But he said the effort’s connection to the White House and AmeriCorps — a national agency that recruits volunteers for community service — is central to overcoming staffing challenges that have plagued efforts by schools and nonprofit organizations to scale up tutoring efforts since the beginning of the pandemic.

“Everybody has been trying to solve this in their own little microworld,” he said.

Working with colleges, large employers like Starbucks and Target, and established nonprofit organizations serving youth, Balfanz said, should develop the Partnership into the national tutoring corps that experts have been recommending for several years. AmeriCorps will also spend $20 million to help organizations recruit and train tutors.

In March, President Joe Biden encouraged Americans to “sign up” as volunteers and mentors for students struggling to recover from school closures. The new initiative follows recent Harvard University research showing that learning declines among students were worse in districts slower to return to in-person learning. “What I’m asking for is a level of urgency unlike any level of urgency we’ve had,” Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said last week during the virtual announcement, joined by White House Domestic Policy Adviser Susan Rice. They stressed that districts should be using American Rescue Plan funds for academic recovery through high-quality tutoring, afterschool and summer programs — and if they aren’t, they should start.

The law “requires that 20% be spent on learning loss. But it is increasingly clear that for many districts, that guesstimate was way too low,” said Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, who has argued that districts make students’ academic progress their “north star” for allocating funds.

Tennessee is among the states directing relief money toward tutoring. ALL Corps — which stands for Accelerating Literacy and Learning — began in the 2020-21 school year and now involves over 80 districts, which provide matching funds to participate.

Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn said the state has learned lessons from implementation that could benefit the national effort. The state program, she said, contributed to recent test score results showing that performance in English language arts among elementary students is back to pre-pandemic levels, with students making greater gains than they have in five years. Gaps in math due to learning loss are also shrinking.

But at the district level, students performed better when tutoring was offered during the school day instead of before or after school, and when tutors were paid educators instead of volunteers. Some districts, she said, hire “surplus” educators who don’t yet have a classroom position, retired teachers and those still in teacher preparation programs.

“There is a general misunderstanding that you can just find a body, put them in a classroom and anybody can tutor,” Schwinn said. That’s one reason why she said it’s not “super realistic” to have a “meaningful” national program in place for fall.

Roza added that districts have already approved their budgets for the 2022-23 school year and changing them will require school board approval.

As part of last week’s announcement, the Education Department launched a map showing how other states are using the funds. And building on efforts from Edunomics and Future-Ed, also at Georgetown, the National Center for Education Statistics will track the extent to which schools are spending the money on tutoring and other academic enrichment programs.

“If your children aren’t getting the support they need, you will have the tools to make sure your principal or superintendent or mayor hear about it,” Cardona said. “Funding alone is not going to get it done. If anything, you could waste it. We could be looking back five years from now and saying, ‘Did we do everything we could have done?’ ”

In the American Rescue Plan, Congress set aside more than $1 billion each for summer and afterschool programs, and the department has encouraged districts to use relief funds to enlist community-based organizations to help students catch up and reconnect to school.

With summer programs already in progress, Cardona urged districts to find a balance between engaging programs that interest students and ensuring that tutoring efforts are tightly connected to what students learn in school.

Since 2020, the administration has urged districts to use relief funds to help students make up for lost learning over the summer. A new report from Education Reform Now highlights how states have fared. It shows that 15 states require districts to join with outside groups to serve students over the summer. But just 10 states have requirements on how long such programs should be and how many hours they should devote to academic instruction.

Arkansas, Connecticut, Louisiana, Mississippi and Washington, D.C. require programs to have one staff member for every 15 students, a ratio backed up by research. The report noted that state officials worry that adding dosage and staffing requirements would discourage programs from applying for grant funds in light of “widespread reporting” on vacancies, turnover and stressed-out staff.

Locating the Partnership at Johns Hopkins, where Balfanz runs the Everyone Graduates Center and is a respected researcher on dropout prevention and improving school climate, increases the focus on using proven strategies.

“This is not just somebody helping you with homework every third Sunday. What we need is really high-intensity tutoring. It’s multiple connections with your mentor in a week,” Balfanz said at last week’s event. “If you’re only showing up once every 21 days … you’re not there to give support in the moment when it’s needed. That’s really what turns the kid around when they know there’s someone there that has their back.”

Jodi Grant, executive director of the Afterschool Alliance — one of the organizations involved in the Partnership — said working with AmeriCorps is also a “terrific way” to address the staffing challenges facing afterschool programs.

Michael Smith, CEO of AmeriCorps, has the same expectations for school districts.

“We know that this partnership will lead to an increased pipeline of educators,” he said, noting City Year, Teach for America and the College Advising Corps as proven examples. “When young people are working in the schools, working next to children, they get a spark. They get ignited, and the data is showing us that they stay … in the education system.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)