Democratic School Choice Advocates Struggle to Be Heard Over the Din of COVID, Trump & Recession as Virtual Convention Ushers in Election’s Final Phase

Updated August 18

Every four years, education reformers dare to dream that a presidential election will finally hinge on the issue of school choice. And each time, their hopes are crushed as wars, recessions and scandals bump their top priority out of the spotlight.

The unique conditions of the 2020 election, in which a deadly pandemic and a free-falling economy have pushed most other issues to the periphery, have made it especially difficult for education activists to demand the focus and commitments of candidates. But even in the absence of COVID-19, this would have been a dispiriting election cycle in the midst of a challenging transition.

The tenure of Betsy DeVos as education secretary supercharged an existing political rift around charter schools, with Democrats at both the state and federal levels increasingly pushing to block the sector’s further growth. In an even more alarming development early this year, DeVos herself proposed to eliminate the Education Department’s Charter Schools Program, a relatively modest federal initiative that had previously enjoyed protection from both parties.

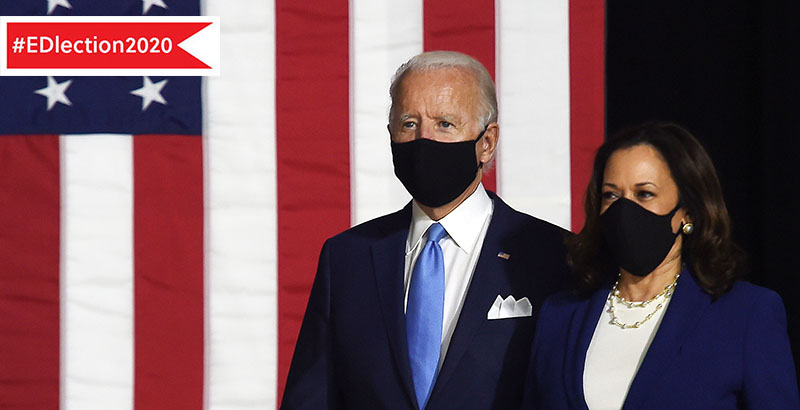

With the Democratic National Convention beginning today, the campaign has entered its final phase. In Kamala Harris, Joe Biden has chosen a running mate with no obvious connections to education policy; insofar as the party’s platform addresses charter schools, it is solely to promise more regulation. To the wide assortment of pressure groups, think tanks and policy entrepreneurs who have made it their focus to expand educational options for American families, the moment is a moment for regrouping and, perhaps, retrenchment.

Perhaps no one is more familiar with the political landscape around school choice than Nina Rees, president of the influential National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. A former high-level staffer in the Department of Education, she served as an education adviser to Mitt Romney’s thwarted presidential campaign in 2012.

Asked about the diminishing bipartisan support for charters, she maintained that powerful Senate leaders like Cory Booker and Ted Cruz were still committed to their success. But the two largest teachers unions in the country, the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association, have exercised “more leverage and power” in 2020 than in previous presidential elections, she added.

“When President Clinton became president, he didn’t have the unions to thank for his presidency,” Rees remembered. “Certainly, President Bush didn’t have to thank them. … Of course, Donald Trump didn’t need the unions to win. So for the first time you really have both of the teachers unions in the mix. They’re out there to get teachers excited to vote, and unfortunately, the rhetoric around charters is one of the things they use in order to get their base mobilized.”

At the local level, the influence of labor has increasingly been expressed in the demands of dozens of unions for states to implement moratoriums on further charter growth before they will return to in-person learning this fall. In Democratic politics, their reach may be even more significant. Lily Eskelsen García and Randi Weingarten, the leaders of the NEA and AFT, both sat on a task force charged with hammering out differences in education policy following the Democratic Party.

The product of that task force was a set of recommendations that largely ignored charter schools except to acknowledge “the need for more stringent guardrails to ensure charter schools are good stewards of federal education funds.” That language was replicated word for word in a draft platform that the party released in late July.

The documents are “a disaster,” according to Keri Rodrigues, a Democratic organizer in Massachusetts and a vigorous defender of charter schools. But she added that presidents have never felt bound by the commitments laid out in their party platforms, still less by the aspirations of working groups scribbling in hotel conference rooms. Moreover, Biden’s eight years of service under Barack Obama, whose administration promoted school choice with significant federal resources, belied the notion that he would side with charter schools’ harshest critics.

“If [Biden] was that diametrically opposed to charter schools and school choice, don’t you think we would have heard it by now?” she asked. “The dude needs to say what he’s got to say to get the support of the people he needs and build the coalition that will win him the presidency. I don’t think that, in his heart of hearts, he hates charter schools.”

Rees agreed, observing simply that “governing is different from running for office.”

“I think the partisan heat will dissipate because once it’s time to govern,” she said. “You have to bring parties together, and you can’t govern with only the folks on the extremes leading the charge. You have to convince a lot more people to side with you. So this issue, I believe, still has bipartisan support.”

But one recent episode provided a look into the fissures that have arisen within the movement. After Rees’s National Alliance invited Weingarten to appear at the group’s virtual conference in July, some charter advocates loudly protested. Vociferous union critic Jeanne Allen wrote that there was “no productive role for an AFT president to play in charter schools,” noting the part the organization had played in a lengthy strike that led to the unionization of a Chicago charter network.

Rees soon announced that Weingarten’s appearance would be scrubbed from the conference agenda, owing to “the complexities confronting our movement,” though she had hoped the discussion would have yielded ideas for how district and charter schools might collaborate to address the academic setbacks faced by students who haven’t set foot in schools since March.

“Some of us in K-12 public education understand the power of working together in a time of crisis, including with those with whom we disagree,” she wrote. “Others choose to look for any opportunity to elevate themselves and sow seeds of division. It is disappointing.”

Allen countered that “it’s difficult to partner with people who’ve devoted their life to calling for the destruction of everything you’ve spent yours building.”

“The view that Randi Weingarten shouldn’t be given a platform at a conference for charter schools isn’t just mine,” she told The 74, adding that “several, well-respected minority leaders in the civil-rights community” see the union as barriers to their fight for educational equity.

Looking past the epidemic, Rodrigues said that choice advocates needed to overcome the unions’ “50-year head start” in organizing capacity. Comparing the movement’s political strength unfavorably to that of the unions, she argued that the disappointments of 2020 have shown that school choice advocates have to take more aggressive steps to cultivate allies and punish opponents. Simply relying on wealthy patrons, or making the public case for the benefits of charter schools, isn’t enough.

“We have not done the kind of organizing work, the power building, to instill fear at the heart of the Biden campaign,” she said. “Because that’s what it is, a fear proposition. We haven’t built that kind of power because we thought we were smarter than playing the game. But if we were going to win this based on a spreadsheet, we would have won it already.”

Rodrigues has put her recommendations into practice, co-founding the National Parents Union in 2019 as a vehicle to draw more attention to the voices of families who favor school choice. Activists executed a few political theater coups during the primary, gaining an audience with then-candidate Elizabeth Warren in an attempt to win her support for high-performing charters like those in her home state of Massachusetts.

But the spread of COVID has put an end to most forms of political organizing, and the home stretch of the presidential campaign has clarified priorities, Rodrigues said.

“This moment calls for me to go all in for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, because my people are going to die under more Donald Trump.”

Some believe that the massive learning losses inflicted by the pandemic have also made it harder for the familiar debates around school choice to win any airtime. Kevin Huffman, a former state education commissioner in Tennessee and now a partner at the reform-oriented City Fund, said in an interview that yesterday’s political divisions “feel pretty irrelevant” in the wake of the coronavirus.

“I almost feel like everything is out the window,” he said. “The old way of having fights about charters versus district feels incredibly irrelevant in a year when a majority of low-income kids of color in this country may not go to physical school this school year. It’s just hard to imagine how the politics of six months ago map up against that reality in any meaningful way.”

Huffman said that the reality of the coronavirus meant that education leaders would need to adopt new goals in the near future, pivoting to the fight to keep existing learning disparities from widening even further in the months ahead. To that end, he said, it was important to “look more to the parents moving forward, because it’s pretty clear that parents do not have monolithic viewpoints about what kinds of things we offer them in schools.”

Any attempt to relitigate the benefits of choice programs like charter schools and school vouchers would only alienate parents for whom the sole focus will be the academic and social development of children who have spent months, and perhaps years, disconnected from their schools, Huffman concluded.

“People trying to exploit the COVID crisis to have a discussion about the things they’ve always wanted to fight over — I don’t think that’s going to be an effective strategy.”

Disclosure: The City Fund and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to the National Parents Union and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)