DC Charter’s Project-Based After-School Program ‘Wows’ in Its Results for English Learners, Expands to District Schools

See our full coverage of National Charter Schools Week

Washington, D.C.

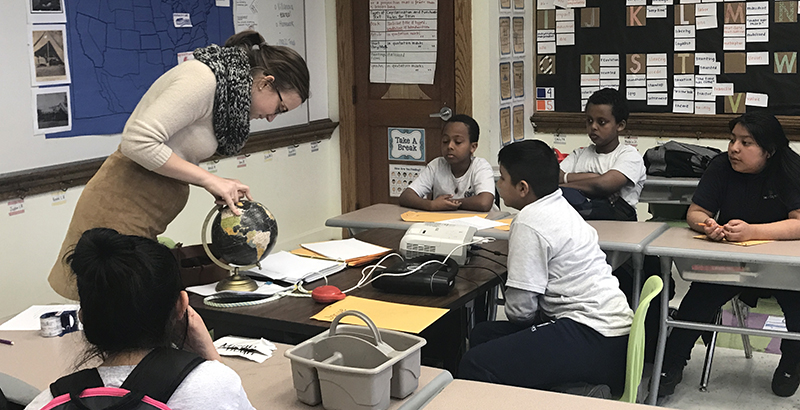

Teacher Nicole Battle was deliberately playing devil’s advocate with the second- and third-graders gathered in her classroom after school on a sunny Monday in April.

Why should girls go to school when they just grow up to stay home and take care of kids? she asked. Why does it matter if immigrant families are split up? It’s fine for some people to have dirty brown water come out of their taps. It’s safe, right?

The seven students gathered for her section of ESL After the Bell, an English language enrichment program at the Brightwood campus of Center City Public Charter Schools, had other ideas.

Girls should have the same rights as boys — after all, boys wouldn’t be here without girls, Seiey Ruiz said. The U.S. citizen children of immigrant parents shouldn’t have to give up their mothers and fathers. And, one of her classmates piped up, some strangers are kidnappers. The brown-water comment roused a universal “Ugh!” from the students.

When discussing each of the problems, the students also talked about young women leaders trying to solve them: Malala Yousafzai, who became the youngest Nobel Prize laureate for her work on educating girls, for instance, or Mari Copeny, also known as Little Miss Flint, the 10-year-old advocate whose community’s water was poisoned by lead.

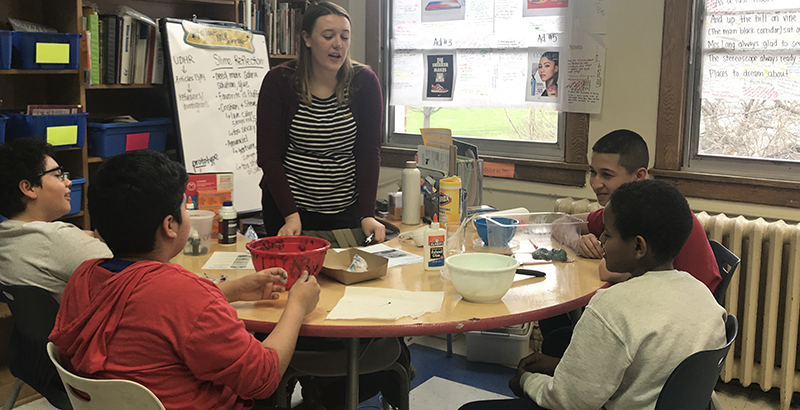

The ESL After the Bell program serves 70 students at three of Center City’s six campuses with large populations of English learners — and for the first time this year, a district public school. All the students are studying human rights issues this year. Each group invented a different product — T-shirts were a popular option, as was homemade slime — to present at a May 9 “universal exchange market” with the aim of raising both awareness and dollars for charities that support human rights causes.

“It’s pure enrichment. It’s lively classrooms with students talking. They love it. They want to come back,” said Isabella Sanchez-Pimienta, lead teacher for ESL After the Bell at H.D. Cooke, the district public school implementing the program for the first time this year.

Though traditional district and charter schools are often portrayed as being in conflict, competing for the same students and public resources, it hasn’t been a problem in this case.

In D.C, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education chose Center City Public Charter Schools to receive a $172,800, two-year federal grant designed to encourage the sharing of charter school best practices and promote district-charter collaboration. Part of that money went toward expanding ESL After the Bell to DC Public Schools.

Sanchez-Pimienta knew Alicia Passante, the charter network’s ESL program manager, and how successful the after-school initiative had been at Center City. She saw it as an opportunity for Cooke as well.

“The data that she showed us was what made me really think, ‘Wow,’ ” Sanchez-Pimienta said.

The grant also pays for shared professional development for teachers from Center City and H.D. Cooke, stipends for curriculum development, and Spanish-language programs at two Center City campuses.

At Center City’s Brightwood campus, about 30 percent of students are English language learners, more than double the citywide average. Of those ELLs, Spanish is the first language for 60 percent, and Amharic, the native language of Ethiopia, is the first language for the remaining 40 percent.

The program started at the network’s Petworth campus six years ago, Passante said. Though the school was getting top ratings from the city’s charter school board, there was a wide gap in performance from its English language learners.

Center City — the first Catholic-to-charter school conversion in the country — is small enough that it has only one class per grade.

“So when you consider what that really meant, these kids are sitting in the same class, receiving the same instruction, as kids that are getting it, and they’re performing great. There’s some sort of disparity as to why. There’s obviously some sort of barrier,” Passante said.

After the first year of the now-six-year-old program at the Petworth campus, participating students’ English and math test scores increased by 30 percentage points, and half of participating students exited the formal English-language-learner classification, according to a report by New American Foundation analysts Amaya Garcia and Conor Williams, who is also a 74 contributor.

Now, English learners across the network are outperforming their peers: 32 percent reached grade-level standards in math and 19 percent in reading in 2017, compared with 21 percent and 17 percent for English learners citywide, according to Center City’s annual report.

The program changes curriculum every semester — often, lately, with a political bent. Last year focused on the environment. The first semester this year, the students wrote self-reflections that embraced their immigrant heritage. The second semester used the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, including rights of immigrants and refugees, as base material.

The project-based learning model allows students to pick up language and additional background knowledge that isn’t part of the school’s standard curriculum but is often related to it. Second-graders this year, for example, made connections between slavery in a class lesson on the Civil War and human rights issues that are part of the after-school program, said teacher Alexis Fields.

Getting the students speaking in English is also an important focus, Fields said.

Elsewhere at Brightwood on that Monday, fourth- through sixth-graders were focused on refugees. After wondering why refugees can’t “just break in” to other countries, and discussing why receiving countries might not want them — fear of differences, for instance, or danger that could follow refugees — they focused on T-shirt designs. They debated between a logo of joined hands over a heart, with a slogan of “Everyone Is Human,” and a new contender of an open birdcage.

Seventh- and eighth-graders were deep in the product design process, researching new recipes for the slime they planned to bring to the market.

Some slime recipes were too colorful and needed more water, which also helps make the product less sticky, Ivan Quintanilla, a seventh-grader, explained.

Ivan has “really learned a lot” and mentioned finding out more about women’s rights, his mom, Esmela, said later through a translator. Ivan has taken the initiative to look up information on his own, she added.

The program has morphed several times over the years: One early iteration required teachers to write their own curriculum for four days of enrichment, which was too hard on educators already working a regular school day. But school leaders have stuck with it after seeing the kind of results it achieved.

Now Passante, who was one of the original teachers working those long hours, writes a new curriculum every year that teachers across the three Center City campuses (and, this year, H.D. Cooke) can use.

The teachers at Cooke haven’t gone through the data yet to see if there have been changes so far, but anecdotally, it’s working for the 60 students it serves, Sanchez-Pimienta said.

One student who has been in the U.S. only a year rarely speaks in class, and she set a goal to speak to three people who came by to see her self-portrait and personal narratives during the first-semester showcase.

In the end, she spoke to every person who came by, Sanchez-Pimienta said.

See our full coverage of National Charter Schools Week

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)