D.C. Sees Warning Signs Teachers are Considering Leaving Jobs Amid Weeks of Uncertainty, Stress Over How District Will Open Schools

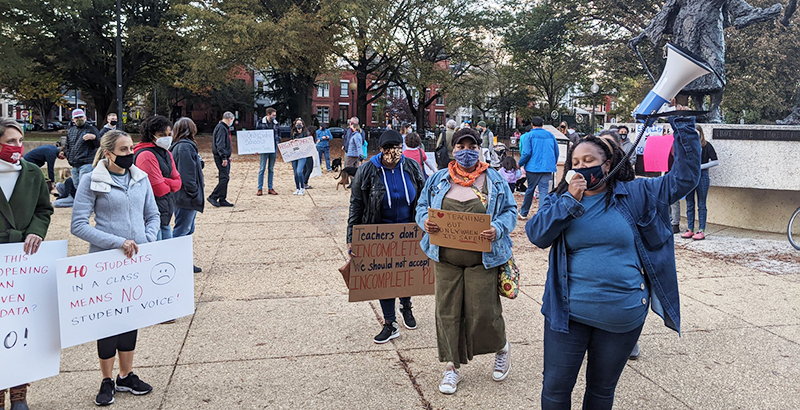

In the weeks leading up to DCPS’ announcement Monday that it would cancel a Nov. 9 reopening, there were red flags that a growing number of teachers were considering leaving their posts.

The Washington Teachers Union fielded more requests for information on early retirement “than in the six years I’ve been there,” president Elizabeth Davis said. Nearly 40 percent of about 180 DCPS elementary school teachers surveyed said they were actively rethinking staying on, largely because of the district’s plan to bring up to 21,000 pre-K to fifth graders back to school in November.

The Council of School Officers, too, was handling three to five calls a week from administrators such as principals and deans of students saying “I have to quit,” president Richard Jackson said.

In a city where teacher turnover rates are already well above the national average, the risk of losing educators fearful for their health and frustrated by a lack of transparency and collaboration with reopening planning has loomed large. Especially when teaching experience is crucial, student stability is paramount and staffing socially distanced, in-person classrooms will likely demand more, not fewer, educators and staff.

“It’s going to be unbelievable how many teachers don’t come back” after November if DCPS doesn’t change tack, Frazier O’Leary, who taught in D.C. public schools for 47 years and now chairs the D.C. State Board of Education’s Teacher Retention Committee, had told The 74.

D.C. councilmember Elissa Silverman voiced similar concerns at an Oct. 23 council hearing. “I am concerned,” she said, “that we are at risk of losing some of our most dedicated and talented educators if they see no other way to be safe than to resign or retire.”

After talks with the teachers union collapsed, DCPS on Monday cancelled its Nov. 9 reopening plan, announcing all students would continue virtually as the district crafts another plan to staff in-person learning classrooms. The district and the WTU had failed to agree on the full criteria for a safe return to schools, and whether every teacher — not just those with a qualifying reason, like a pre-existing condition — should have a choice to not return.

While advocates like Davis called the delay “a temporary win,” an agreement is still elusive. And teachers who’ve spent weeks in a cloud of stress and frustration said it’s going to take more than the delay to earn their trust and keep them around. Along with some D.C. Council members and advocacy groups, they’re demanding educator and community engagement.

Teachers are “definitely watching every step” the district makes, said Tiffany Brown, a special education teacher at Miner Elementary in Ward 6. She would leave the district before returning to a classroom currently because of her asthma and deep distrust that buildings are ready to open.

“It’s just a matter of time before teachers are going to be asked to come back,” she said. “And then they’re going to have to make some really hard decisions.”

Advocates in D.C. are particularly worried about retaining educators of color, who make up about 60 percent of DCPS’ more than 4,000 teachers. Andrea Flood, a H.D. Cooke Elementary teacher, said at an EmpowerEd briefing last month many of these educators “are stressed,” facing a three-pronged dilemma: A virus disproportionately affecting their communities, racial tensions, and a lack of confidence in DCPS’ reopening planning.

The initial intent was to welcome up to 7,000 students back for in-person instruction with teachers Nov. 9, followed by 14,000 more kids later in the month who would continue virtual classes under adult supervision. That second piece of the plan is still in motion.

Davis on Thursday confirmed the union is back at the negotiating table with DCPS.

When it comes to teacher turnover, D.C. surpasses most comparable urban districts, like New York and Chicago, with an average 25 percent school-level turnover rate across its district and charter schools annually. It’s a nationwide concern, too, from Fort Worth, Texas to Tallahassee, Florida, with the U.S. already facing teacher shortages pre-pandemic.

(Experts do note a “mass exodus” trend has yet to emerge, with retirements down in states like Indiana while up in states like New York.)

Replacing teachers is costly — on average, more than $20,000, according to the Learning Policy Institute. And even if they stay with the district but switch schools, it can be detrimental to students’ learning, especially when a teacher is considered “highly effective.”

“Ask a student in any grade: How many times did you form a special bond with a teacher, and then you come back into the building [in August] and you can’t find them anywhere?” high school junior Alex O’Sullivan said at an Oct. 23 hearing in support of a bill that would require more public dissemination of teacher retention data. “The most important adult relationship for a child outside of their family is with their teacher.”

Teachers said retaining them requires an array of changes beyond collaborating with them on reopening, such as pausing teacher evaluations and working toward limiting — or getting rid of — mayoral control of the school system.

DCPS in a statement said it had retained more than 95 percent of its “effective” and “highly effective” teachers going into the 2020-21 school year, with 87 percent of its teachers returning “to the same school where they taught the previous school year.”

“Ensuring we have excellent educators in every classroom remains a top priority,” a spokesman said. He added the district has received a $30 million federal grant that “will focus on prioritizing recruitment, rethinking teacher preparation [and] enhancing professional development.”

Exacerbating an existing issue

DCPS’ higher-than-average teacher turnover rates have been linked to broad opposition to its teacher evaluation system, which ties educators’ performance to students’ standardized-test scores, along with a reported lack of professional development support and respect.

The embattled reopening process, teachers said, exacerbated those issues.

Sam Magnuson, a fourth grade teacher at John Eaton Elementary in Ward 3, told The 74 last month she’d consider leaving if she was forced to return to class. While she’s happy now to stay with her students, Magnuson acknowledged that these abrupt changes and ongoing uncertainty aren’t sustainable for her or the children.

She’d just let her kids know last Friday — the same day she hosted a lively virtual Halloween party — that she might not be their teacher anymore. “It was tough. There were a few tears,” she said. “And then just a lot of questions.”

Katherine, a pre-K teacher in Ward 4 with a pre-existing condition, was confirmed to teach virtually before plans were delayed. But she said the mismanagement around reopening has left a bad taste.

“It has me reconsidering how long I want to remain with DCPS … as I plan for the next couple years,” she said.

It’s difficult to gauge whether the city’s 66 charter networks, which on the whole have reported similar teacher turnover rates to DCPS, could see higher rates this year. At least a third are reportedly offering either limited in-person support or a hybrid model; the D.C. Public Charter School Board said retention data from each charter is coming later this year.

At a recent EmpowerEd briefing, though, a few charter teachers voiced similar anxieties around buildings’ readiness and safety protocols — and frustration that they, too, have been largely left out of reopening discussions.

“Charter schools have their own way of doing things, but oftentimes they will follow what DCPS is doing,” said James Tandaric, an ESL teacher at Center City Public Charter Schools. “My biggest worry is if we have a plan at DCPS like this where there is no communication and no follow through with teachers, it’s going to be the same with charter teachers as well.”

Beyond the teaching workforce, the risk of higher turnover extends to school administrators as well.

Last month, Jackson, the president of the Council of School Officers, told The 74 his union was spending “an exorbitant amount of our time trying to convince people to hang in there.” He was fielding three to five calls a week from school administrators, like principals and deans of students, who were seriously considering quitting.

Principals not being fully involved in reopening planning is “destroying” morale, Jackson said. He’d penned a letter to DCPS and city leadership in late October on behalf of principals, outlining perceived flaws in the plan.

Ferebee on Monday did suggest intentions to work more closely with school administrators. Asked what the future reopening plan would look like, he said, “We may approach it differently. We are engaging with our school leaders. We want to get more of their feedback.”

Solutions

There are a litany of things educators said the district and city can start doing to build trust.

“At the most basic level … answering questions” posed at future virtual forums and town halls, Katherine said. Other asks include suspending — and rethinking — teacher evaluations while the COVID crisis persists and focusing on student growth, as well as investing in and promoting outdoor learning opportunities.

DCPS said it’s taken a host of actions to improve retention over the years, including offering among the highest teacher salaries nationwide (more than $76,000 on average), partnering with local schools of education “to develop strong teacher pipelines” and creating the Leadership Initiative for Teachers, which “provides high-performing teachers opportunities for advancement inside the classroom.”

Some, like former teacher O’Leary, say reinstating trust will take something bigger — new leadership. Notably, an end to mayoral control of D.C. schools, which many argue has perpetuated a top-down structure of decision-making. (That power lies with the D.C. Council).

Seeking more transparency, O’Leary and the State Board of Education are advocating for a bill that would require, among other things, the annual publication of school-level teacher data — including breakdowns by race, state of residence and years of experience — which proponents believe would start to illuminate which teachers stay versus leave, and why.

The bill drew skepticism at a late October hearing from a few local think tanks and council members like education chairman David Grosso, who pointed to existing data and collection efforts and are wary raw data could be misinterpreted without expert analysis and context.

A teacher later in the hearing shot back. “One major reason that teachers leave is the lack of basic respect,” she said. “This legislation is the least you can do.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)