Creating the Next Generation of Digital Innovators at Washington, D.C.’s First Computer Science-Focused Middle School

By Emily Langhorne | January 30, 2019

Washington, D.C.

“When I finish writing the statement, that cat will move,” promises Deshaunte’ Goldsmith, a sixth-grader at Digital Pioneers Academy Public Charter School. She presses enter on the keyboard and, sure enough, the animated cat on her screen begins to pace back and forth.

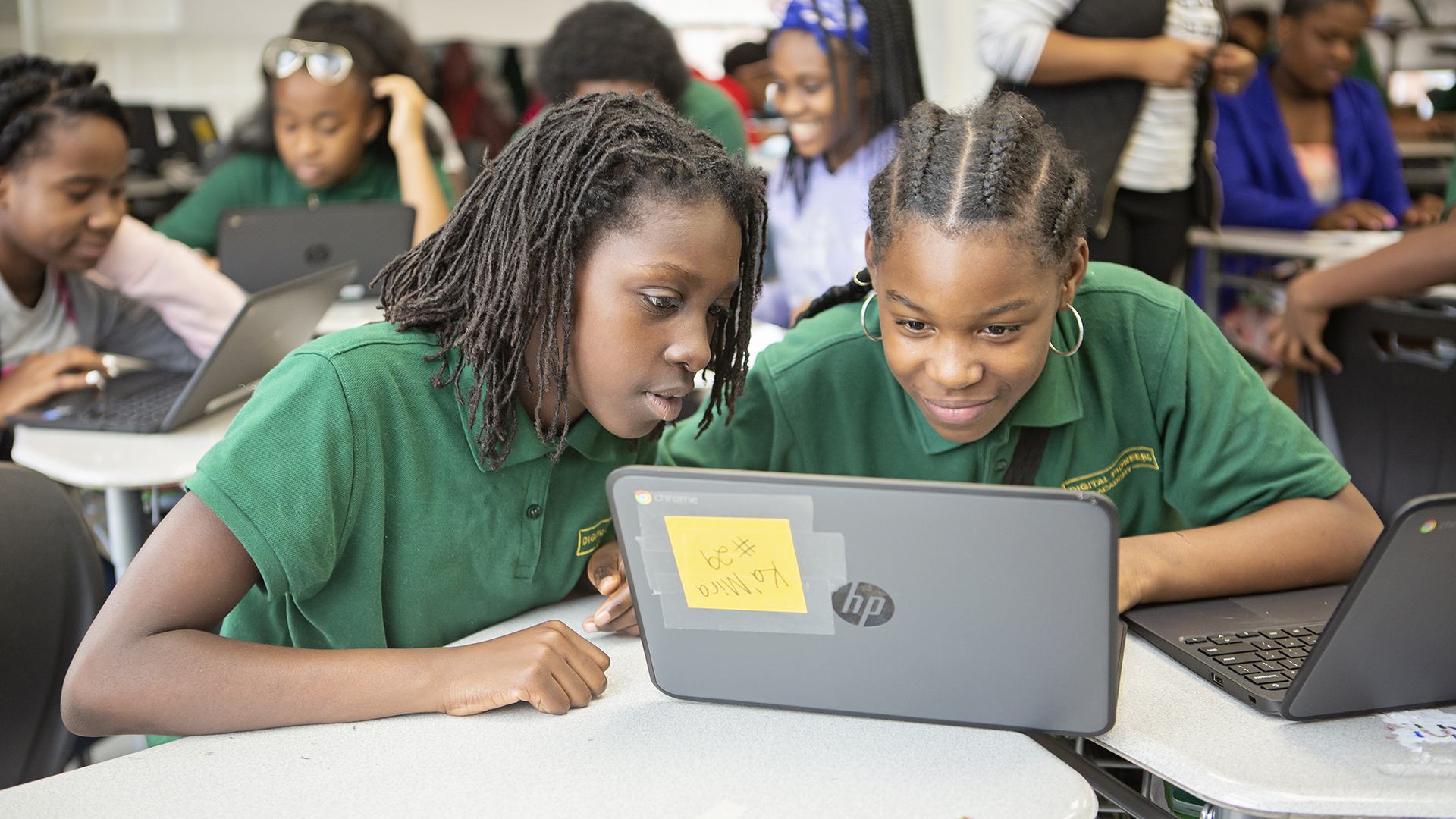

Goldsmith is a member of the founding class at the school known as DPA, Washington, D.C.’s first computer science-focused middle school. Opened in August, the school is small, serving about 120 sixth-grade students across four classes, but has plans to build out to 12th grade. Every day, students take computer science as a part of their core curriculum.

Today, in computer science, Goldsmith is learning how to write conditional statements — such as if the space bar is pressed, the cat will jump — using MIT’s animation-based platform Scratch. First, the students have to identify conditional statements, and then they have to write their own. At the end of class, they have to find and correct the error intentionally planted in the teacher’s code.

“The error’s in the third line of code,” Goldsmith says. “It’s missing part of the conditional statement.”

DPA occupies the second floor of Washington Heights Baptist Church in the Hillcrest neighborhood of the city’s seventh ward. Ninety-eight percent of the students come from wards seven and eight, D.C.’s poorest neighborhoods, and, because DPA’s leadership recruited heavily in the local area, two-thirds of the students went to the neighborhood elementary schools.

“My decision to go to this school was sort of last minute,” says Goldsmith. “I was waitlisted at Friendship Charter School. Then I heard about this school, and I decided I wanted to come here and learn about code. All of the teachers here have really supported me, and this is one of my favorite classes. I’m happy I ended up here.”

Lamontae Allen, Goldsmith’s classmate, or teammate as they are known at DPA, also loves the computer science curriculum.

“Computer science is my favorite class,” he said. “I like to play video games. When I grow up, I want to be a famous YouTuber, but if that doesn’t work out, I might make my own computer game, and learning all of this will help with that.”

Today, only 40 percent of America’s K-12 schools teach computer programming, and computer science-focused schools like DPA that do not require admissions tests or screen their applicants are rare. Low-income families often lack access to technology, and the racial achievement gap in the tech industry is well documented. Less than 3 percent of Google’s workforce is African American.

“Our mission is very simple,” says Mashea Ashton, DPA’s founder and the head of school. “We want to develop the next generation of innovators. We want our students not just to consume the digital economy, but to be a part of creating it.”

A veteran educator embraces comp sci

With almost 20 years of experience teaching in and running public charter schools, Ashton knew she wanted to leverage her experience as an educational leader to positively impact Southeast Washington, D.C. — a historically underserved neighborhood she cares deeply about. Ashton began her career as a special education teacher just down the street from DPA’s current location, and her husband, a sixth-generation Washingtonian, grew up in the neighborhood.

Ashton herself has no computer science background. “I took one computer science course at the College of William and Mary back before they even had email,” she jokes. “However, three years ago, when I began thinking about opening a school, I thought about a college prep model, but the more I thought about students and families and options, the more I thought about the importance of being career ready. Then, I saw the data about how many high-paid, high-demand jobs in computing go unfilled every year.”

DPA’s curriculum is a modified version of the academic program developed by RePublic Schools, a network of charter schools throughout the South that teaches computer coding daily as part of its college prep curriculum. With this curriculum, DPA students begin by working on elementary programs like Scratch before learning two of the core internet technologies, the markup languages HTML and CSS, or Cascading Style Sheets, which determines the look and layout of a webpage’s content. They eventually move on to JavaScript, a more advanced language and the third of the core internet technologies. After mastering JavaScript, students will have the opportunity to explore other advanced programming languages such as Python and R.

Although DPA currently holds a charter only for a middle school, Ashton plans to apply to expand the school through high school, building up one grade at a time. During high school, students will be expected to pass the Advanced Placement computer science exam in 10th grade, she said, and become fluent in two coding languages by the time they graduate. Juniors and seniors will also participate in internships and work-study programs that allow them to gain real-world experience in the tech sector.

DPA is already building a pipeline of partnerships with tech firms, like Microsoft and Deloitte, and three times a year, middle schoolers will have “expeditions,” three-day experiences where they demonstrate some of the coding skills they’ve learned to tech experts before visiting the experts’ workplaces.

“When you think about the job quality and the job opportunities that our students will have because they had one hour of computer science each day from sixth to 12th grade … it’s incredible,” says Crystal Bryant, a STEM teacher at DPA. “It’s refreshing to see someone like Mashea come in with a vision to change the trajectory of the lives of kids in this area.”

Founding a school that celebrates science

When designing DPA, Ashton and her team researched broadly to learn about the best models for a computer science-focused school. In the spring of 2017, Ashton taught an elective, “Design the Academy of the Future,” to ninth-graders at Washington Leadership Academy Public Charter School, a technology-focused high school in D.C. She heard from students about the factors of their education that have had the greatest impact on their motivation and learning. Understanding the real-world application of the skills they were learning ranked at the top of the list.

“Students didn’t need to be told about the number of high-paying computing jobs available; they needed to have real-world experiences, to see the real-world connections for what they were learning,” says Ashton. “They wanted to know the ‘why’ for everything. ‘Why am I taking notes? Why am I reading Shakespeare? Why am I doing Scratch?’”

Ashton also spoke with the leaders of the Academy for Software Engineering, a computer science-focused school in New York City. The school’s leaders said they had initially recruited tech experts to serve as the teachers, but they ultimately discovered that they needed people who were experts in instructional delivery, classroom management, and working with teenagers. The RePublic curriculum, however, is not expert-dependent, so Ashton could recruit widely for her teaching staff.

“None of our teachers had ever taught computer science as a core part of the curriculum before,” she says. “We recruited educators who believed in our mission, had the best achievement record for working with kids like ours, and who were excited to be on a founding team, which is very different from a regular teaching job.”

What being a founding teacher means, Ashton says, is long, hard hours and owning the successes and failures of the school. “There’s the opportunity for growth, but there’s also going to be some failing forward, which is an important part of growth and a value we attempt to impart to our students,” she says. “I do think our teachers are feeling the success of what it’s like to work together on a team with a shared mission and vision where everyone is accountable.”

Bryant, the STEM teacher, came to DPA because she felt that in urban education, science often isn’t considered as important by school administrations as math and English, the major testing subjects. She wanted to move to a place that celebrated science and computer science, rather than treating it as an elective. At DPA, she was given the opportunity to build a STEM program.

“A lot of people warned me about joining a founding team. ‘It’s a lot of work,’ they kept saying, but I think it’s going to be rewarding to look back and see all of the computer scientists that our school has produced and know I helped create that,” she says.

“No one is just a teacher here,” adds STEM teacher Ashley Pettway. “A lot of times in urban education, you feel like you’re a part of a system where you have no control, but here, anything that we dream up for our kids, so long as it’s mission- and vision-aligned, is supported. We can do it. I’ve never worked in a place like that.”

High empathy, high expectations

DPA’s classrooms have arched attic ceilings and an airy, homey feel. The school renovated the second floor of the building before moving in, creating four large classrooms and some smaller meeting rooms. Backpacks are hung along the classroom walls, and there are comfortable sitting areas for students in addition to more traditional desks.

“Our scholars learn better when the environment is conducive to learning,” says Ashton. “I hope they feel like these are their rooms.”

To minimize transition times, students don’t switch classrooms; instead, the teachers do. Each class always has two adults, the classroom teacher and an assistant, who is often a dean or another member of the administrative team.

The school day runs from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., except on Wednesdays, which are half-days. Students have study hall, math, computer science, social studies or science, an intervention period for struggling students, two classes of English Language Arts, and recess, daily. There’s a break in the morning and a second one in the afternoon. There’s also an a.m. and p.m. community meeting and a mandatory enrichment activity — like kickball, dance, creating holiday cards, and more — from 4 to 5 p.m. It’s a long day, but many of the students come in significantly behind grade level, so there’s a lot of work to be done. When the school year began, only 20 percent of the founding class was on grade level in both reading and math.

“We tell our scholars that if they want to achieve, then they have to outwork everyone, and they’re learning and beginning to own that,” says Ashton.

Classmates give each other “snaps,” impromptu snapping, to celebrate when a teammate does something well. There’s also a school-wide hand sign for “giving magic,” which is wiggling fingers at a teammate to send good them vibes.

“We are team, so we want to support one another, but we don’t have a lot of spare time. Our silent celebrations give students a lot of joy, but they aren’t disruptive to learning,” says Ashton.

Students can also earn a “professional” point each class period if they demonstrate behavior, like optimism, empathy, and growth, that reflects the school’s values. Professional behavior earns a point; unprofessional behavior, like talking back to a teacher or putting your head down in class, loses a point; and neutral behavior results in no change. Students can redeem themselves throughout the period; it’s what they’ve done by the end of class that matters. The system promotes the idea that students have control over, and can change, their behavior. Every morning students fill out their daily behavior goals for each period, and every afternoon they reflect on whether they met those goals.

“Professional and unprofessional is language that kids really understand,” says Bryant. “They know adults have to be professional, so they see the real-world connection. It’s very clear cut, which makes it easy for them to articulate reflections on their behavior and even write things like, ‘I was slouching in my seat and not participating yesterday so I wasn’t being professional.’”

If a student has a “community violation” — swearing at a teacher, starting a fight, etc. — then they receive an automatic “unprofessional” and are removed to the “reset room” for the remainder of the period. There, they fill out a reflection on their behavior and brainstorm how to make amends to the teacher and the community before returning to their next class.

Students can spend professional points at the school store. They can purchase dress-down days, Subway cards, a chance to visit friends in another class during break, and more. However, the four students who have the most professional points at the end of the week get a pass to “The Lab,” where video games, a movie projector, a basketball hoop, and more await. Staff asked the students what they wanted prior to stocking The Lab.

“There are Xboxes and TVs and everything,” says Pettway. “The first time I went into The Lab, I thought, ‘It looks like a Dave & Busters.’ I took photos of it to show the kids. It’s such a positive, consistent motivator for them. Ms. Ashton plays Fortnite [a phenomenally popular online game] with them in there. It’s great.”

“School and learning should be fun,” says Ashton. “We do want them to develop intrinsic motivation, but we also want them to understand that hard work and positive actions ultimately have positive consequences.”

“I appreciate that this is a very different experience for our kids than many are used to,” says Bryant. “I have been an urban educator for eight years, and I feel like our kids are constantly being punished for being children or for the things they don’t have. I appreciate that I’ve found a school where the goal is to remove all obstacles that keep kids from learning and then hold them accountable for their learning.”

“It’s called ‘high empathy, high expectations,” says Pettway. “And it’s a model that’s working for our kids.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter