A, B, C, F: Why This High School Never Gives Ds and Teaches Its Students to Think Like Lawyers

By Emily Langhorne | January 24, 2019

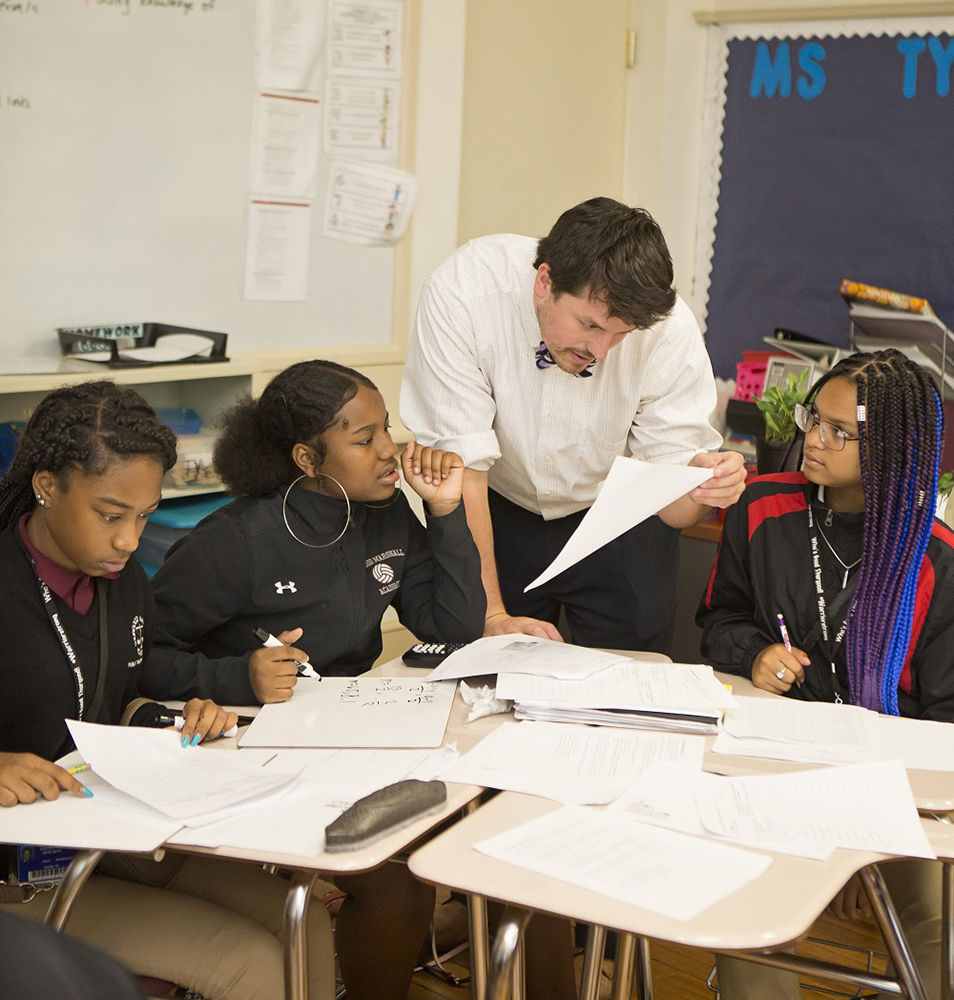

Over 90 percent of the students at D.C.’s Thurgood Marshall Academy live in the city’s two poorest neighborhoods. Every graduate since 2005 has been accepted to college.

Washington, D.C.

“Coats off, scarves off, hats off! Belts on; shirts tucked,” Stacey Stewart, Thurgood Marshall Academy’s director of student affairs, yells at the two lines of students waiting to check in and begin the school day.

“Ms. Stewart, I’m early today,” a student says as he approaches check-in.

“It’s 8:29. You are not early; you are on time,” she says, exasperated and amused. Check-in runs from 8 to 8:30 a.m. After students check in, they head downstairs for breakfast.

Nothing about morning check-in at Thurgood Marshall Academy (TMA) hints that there’s anything exceptional about the school, but a glass case near Stewart, filled with academic awards, reveals the truth: This is an extraordinary school.

Consistently ranked as a top-tier public charter school in Washington, D.C., Thurgood Marshall Academy is a law-themed school that serves about 400 students in ninth through 12th grades. Over 90 percent of students live in Wards 7 and 8, the city’s two poorest neighborhoods. Nearly 100 percent are African-American, and 61 percent are designated “at risk” by the Office of the State Superintendent, meaning they are at greater risk of dropping out based on their receipt of public assistance, food stamps, involvement with the D.C. Child and Family Services Agency, homeless status, or being older than expected for their grade.

The average ninth-grader enters TMA three to four years behind grade level.

Nevertheless, since TMA graduated its first class in 2005, 100 percent of graduates have been accepted into college, over 90 percent have enrolled in college within a year of graduating from high school, and 94 percent persist in college from freshman to sophomore year. The school’s cohort four-year graduation rate (a city calculation that also includes the status of students who have withdrawn or moved to different schools over the past four years) is 78.5 percent, higher than the statewide average of 68.5 percent, and significantly higher than the neighborhood’s district-run high schools, which have rates of 50 and 55 percent. For the past three years, student scores on D.C.’s standardized exams have been among the highest citywide for nonselective high schools.

“As a nonselective, freestanding high school, we don’t have a feeder pattern,” explains TMA’s executive director, Richard Pohlman. “We’re ready to take all kids who come through our doors, so our program has to be diverse enough to take both kids highly prepared and those significantly behind. Our systems and structures are a decade-plus old, but they’ve produced consistent results over that amount of time. What we’re doing works.”

So, what are they doing?

They’re exposing students to law-infused curriculum.

They’re increasing learning by supporting students and teachers.

And, they’re not giving Ds. The grading scale at TMA goes A, B, C, F.

Mastering the 5 essential legal skills

TMA’s goal is not for every student to become a lawyer but for all students to gain competency in the skills that lawyers rely on. The “five essential legal skills” — advocacy, argumentation, critical thinking, negotiation, and research — are woven into the curriculum for all classes.

“We’re always learning about and growing our law theme,” says Pohlman. “It’s not easy to know what a broad mission statement looks like in practice, so we have to work at it. How do we teach skills that are useful for civic engagement? Skills that get kids into college and careers, but also help them become actively engaged democratic members of society? Our history teachers have been remarkable about that.”

Each year in history class, students must complete a law-related project that emphasizes the five legal skills. Previous projects include mock trials, soapbox speeches, issue-to-action projects, and studies of the impact of federal legislation on D.C. Council legislation. In the 2017-18 school year, the social studies department arranged 18 educational trips for students, including a visit to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Students also participate in the school’s law-related programming. In ninth grade, students have Law Day six times a year, when they attend legal workshops hosted at and by local law firms. Sophomores spend eight half-days at Howard University, learning from professors about how law is present in their everyday lives.

During their junior year, students get to know a legal professional through the Law Firm Tutoring mentorship program. TMA partners each junior with a mentor at a local firm. Once a week, students travel to the firm (which provides meals and transportation) and have dinner with their mentor, who helps them with scholarship writing, SAT prep, college research, etc.

“Understanding the law and my rights has made me a better person outside of school,” says Devin Halliburton, a junior at TMA, whose Law Firm Tutoring mentor Yasmine Harik is an associate at Arnold & Porter.

Fellow student Ashleigh Miles agrees. “I’m not going to turn law into a career, and neither is Devin, but the information is good to know,” she says. “The law part, that’s what makes Thurgood unique. We get to meet new people and make connections in that world and learn from them.”

For those students who become interested in pursuing a law career, TMA offers more in-depth law courses. For instance, in Peer Court, students learn about how laws affect school policy, such as the Individuals with Disabilities Act and special education, and court cases, such as Morse v. Frederick, involving students’ free speech. In the 2007 case, the U.S. Supreme Court found a school official had not violated a student’s First Amendment rights by suspending him for displaying a banner proclaiming “Bong Hits 4 Jesus.” Another component of the class involves volunteering on a student-run court, which coordinates with the Office of Student Affairs to assign and monitor consequences for students who have committed minor disciplinary infractions.

“We teach students to advocate for themselves, so we want to listen to them when they do,” explains Pohlman. “Peer Court is a way of doing that. It lets students think about logical consequences for behavior.”

Peer Court, portfolio assessments, and food if you’re hungry

“Ms. Odu!” a student shouts. “Do you want to hear a joke?”

“Hmm. Do I want to hear a joke?” Ms. Odu, her ninth-grade English teacher, pauses. “Yeah, OK, go on, Kamani.”

“What’s the hottest place in a cold room?” Kamani asks. “The corner, because it’s always 90 degrees.” The class laughs, but no one louder than Kamani. Ms. Odu laughs with them.

“That was cute,” she says. “But now, we have to settle down and finish this assignment from the last class in 25 minutes because we can’t spend six years on it. And, remember, your quiz is on Monday. We don’t have school on Friday, so some of you will probably forget. But that’s OK. Because that’s your problem.”

Kome Odu came to TMA in 2012 after teaching in Prince George’s County Public Schools in Maryland. “The standards here are so much higher than at my old school. That matters to me. There’s more rigor and organization and an expectation that kids do more, can do more,” she says. “The administration supports teachers. I like teaching literature to black kids, these kids. That’s what keeps me here.”

The school’s leadership believes that too often in urban education, teachers are asked to perform multiple roles beyond teaching, making it impossible for them to focus on improving their craft and, by extension, student learning.

“The foundation of our school is made from what happens in classrooms,” says Pohlman. “Our teachers’ job is to make sure instruction is great all day long. They need to be supported in that.”

At TMA, deans are in charge of managing school culture and student behavior while the heads of school focus on instructional delivery. Instructional leaders are made aware of behavioral issues, but the deans are responsible for handling those issues.

“We have people whose jobs are very distinct. Everyone needs to have a laser focus on their job to do it well, so we don’t expect teachers to be doing everyone else’s job,” says Pohlman. “We all talk and coordinate, but we have a place — a specific person — to send students to for specific issues and questions.”

Stacey Stewart, the director of student affairs, believes that this division helps assuage behavioral problems. “A lot of our kids have a lot of stuff going on at home, and their behavior is not always a reflection of what’s going on in the classroom,” she says.

The Office of Student Affairs supports students outside the classroom so that they’re prepared to learn in the classroom. Stewart anticipates potential causes of decreased motivation or disruptive behavior. Her office has boxes of snacks, toothbrushes, deodorant, and other things. “If a kid’s upset because he doesn’t have clean clothes, I get him clothes,” she says. “If a student’s hungry, I get her a snack. I take that stuff away from them so that they can focus on learning.”

When behavioral issues do occur, TMA differentiates consequences based on both the seriousness of the infraction and the student. Peer Court assigns consequences for violations of TMA’s “no-brainers” — chewing gum, using devices in school, uniform violations, etc. — while Stewart’s office handles higher-level violations, such as fighting and willful disobedience.

“Some kids respond well to a call home,” Stewart says. “Others will move for one teacher because they have a relationship, but not for another, so bringing in that teacher to mediate a circle conversation helps. A lot of it is understanding what works to move that kid.”

But TMA’s leadership also expects students to own their behavior. The school uses a merit and demerit system. While students can work off demerits by gaining merits, if, at the end of the year, a student has more than 20 demerits, he or she won’t be promoted, regardless of academic performance. However, because grade-level deans host opportunities for students to earn merits over the summer, like classes focused on community service for the school or building positive relationships, this rarely happens. For the past three years, no student has been held back because of behavioral infractions.

Students also reflect upon their yearly progress through a portfolio assessment. Each spring, they give a formal presentation to three faculty members during which students examine their academic performance as well as their behavioral record and overall contribution to the school. And they turn in a portfolio of the materials they intend to speak about.

“I get so nervous for portfolio,” says Halliburton, the junior. “It can be in front of teachers you don’t know, and you’ve got to talk for, like, 45 minutes. They don’t talk. They just write stuff down and look through your binder. You’re explaining everything you did — like your school work and behavior — and why. But it actually really helps me. I save my portfolio projects and look at them to improve.”

A school without Ds

“When I came here in ninth grade, I was behind in reading,” Halliburton says. “My first semester, I got a 69 in English on my report card. At my old school, that would have been a D, but here I was seeing an F. That was like, whoa, I need to start tightening myself up. I’m supposed to be preparing for college.”

Halliburton’s reaction is exactly why TMA grades on an A, B, C, F scale, where anything less than a 70 is an F. The school’s leadership believes that if students don’t know at least 70 percent of the material, they won’t be prepared to pass at the next level. The lack of Ds is not a punishment; it’s a success strategy.

“It’s stressful for freshmen,” Pohlman admits. “Many are accustomed to always just getting by, and suddenly, sliding by is failing. We have a lot of resources to support kids when they’re failing, but they’ve got to work hard.”

Mills, Halliburton’s classmate, knows exactly what he means. “At my middle school, they just passed you on. It didn’t really matter if you got the curriculum or not,” she says. “When I came here, I failed Algebra I the whole first year. But then when I did get to geometry, I went to office hours. I got more help. I didn’t fail geometry.”

Students are eligible to take up to two courses per summer if they fail their courses. If students do not retake a failed course over summer, they either receive an alternative schedule for the following year, which includes the retake, or they retake the course in a subsequent summer. However, for courses that have a specified order, as in Mills’s case, students must pass the prerequisite before moving on to the next level.

Since most ninth-graders enter TMA below grade level, freshman and sophomores take double-block English and math classes. They have twice as much classroom instruction as their peers at traditional high school programs. These double-blocks are a cornerstone of TMA’s success at raising student achievement. Other academic supports include a Summer Prep program that helps students transition into TMA’s rigorous academic environment, an SAT prep class, and a Senior Seminar in which students receive intensive coaching on the college application process, help with scholarships, and lessons on transitioning to college life. The school has a robust college counseling department, with three full-time college counselors.

“Our college acceptance rate is [far] higher than the national average for low-income communities, so we tell parents what our system looks like and ask them to trust it,” Pohlman says. At the end of the first quarter, many parents call him, upset or angry, because their student has never had an F before. “Well, they have an F now,” he tells them. “Let’s help them get out of it.”

“Our ultimate goal is not to have kids take remedial classes in college,” says Stewart. “Because that’s debt on top of debt.”

One national study that looked at 911 two- and four-year colleges found that 96 percent of students there were placed in remedial classes in 2014-15. Remedial classes carry no credits, but enrolled students who cannot pass freshman-level course entrance exams must complete and pay for them before they can enter into credit-bearing courses. Research has shown that a large percentage of students placed into remedial courses drop out before graduating college, and often before even finishing the course.

Both Halliburton and Mills agree that “Thurgood is hard,” but, by the second year, students adjust to the rigor. Moreover, they regard the high standards as the manifestation of the faculty’s belief in their abilities.

“Everyone here wants me to succeed,” Halliburton says. “Teachers have office hours before and after school, and they’ll come to you to make sure you’re straight with their class if they think you need help.”

It’s this combination of rigor and support that draws many parents and students to TMA. The school’s success with students, as well as the demands placed on them, are well known in the community.

“We don’t lure families here under the false pretenses that everyone passes,” Pohlman says. “The part of school choice that really matters is that you have a system with a lot of different choices and that you provide families with as much transparency as you can so that they can make a choice. We’re an important part of that system in D.C.”

Lead image: Social Studies teacher Karen Lee in background teaching seniors Intro to Law in the school’s moot-court-style classroom (Thurgood Marshall Academy)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter