Competitors or Collaborators: Some School Closure Orders Look to Restrict Virtual Charters to Protect Brick-and-Mortar Schools During Coronavirus Crisis

Updated, April 7

While virtual charters have typically earned headlines for struggling academic performance, allegations of enrollment fraud and influential lobbying, the coronavirus pandemic has put the online schools in a new position: as uniquely well-suited to provide education to students amid the global crisis.

Whereas most teachers across the nation are learning for their first time how to virtually educate children — confronting barriers like lack of home internet access and a dearth of online curricula — virtual charters have been able to operate largely unimpeded.

This familiarity with providing remote instruction has raised concern among some public education advocates that families might flock en masse to cyber charters, further disrupting the finances of brick-and-mortar public schools. So far, though, virtual charter leaders have not reported a major surge in enrollment and have stressed publicly that they’re not focused on capitalizing on the crisis. At least some schools, however, have been running new ads on social media, encouraging families to enroll.

As governors ordered public schools closed for the pandemic, most did so in ways that allowed virtual charters to continue operating. For example, Arkansas’s order clarified that just schools with “onsite instruction” will close, and Florida’s guidance shuttered only school “campuses.” Jeff Kwitowski, a senior vice president for K12 Inc., a publicly traded management company for virtual charters, pointed to hurricanes in Florida and Louisiana and wildfires in the West as past examples of when schools closed but virtual charters stayed open.

“It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to close brick-and-mortar school buildings but continue full operations, instruction and student services,” he said. “However, that is feasible for online schools.”

Yet in a handful of states, there was more confusion and outcry, with some closure rules that virtual education providers saw as overly blunt at best.

In Oregon, for example, the state education department announced that their governor’s public school closure order applied to virtual charters too, and it raised concerns about what would happen if too many families switched quickly to the online schools.

Oregon then clarified that its 20 virtual charters could continue their operations but could not enroll new students after March 26. Oregon Department of Education spokesperson Marc Siegel told The 74 that “the primary reason” for this is to ensure that students can access supports they need “without creating further school funding disruptions that would be created by the transfer of students from one school to another.” As of October, 14,047 students were enrolled in Oregon virtual charters, according to Siegel.

Some school choice advocates were outraged, disappointed that Oregon would deny families options at a critical moment — although at least some virtual charters in the state had already reached enrollment capacity by March 26 or were planning to close enrollment regardless.

Shawn Farrens, principal at the Baker Web Academy in Oregon, told The 74 they were always planning to close enrollment by March 30. “Some virtual schools accept kids very late into the school year, but for us, with 10 or 11 years’ worth of experience, we find that if kiddos come in late, it’s not the best scenario for them,” he said. About 2,200 students attend Baker, and had the state not issued its moratorium, Farrens said, they would have accepted just 100 more.

Farrens applied to transfer his own 7-year-old son into Baker from a brick-and-mortar when the state’s closure was first announced in mid-March. “We wanted him to continue with formalized education because my kiddo is easily distracted, so for him to miss out on a few extra weeks of school would be detrimental,” he explained. Now that Oregon’s school closures have been extended even longer, Farrens says he and his wife are “really happy” with their decision and aren’t sure whether they’ll send their son back to his old school when the crisis ends.

Nicholaus Sutherland, the executive director of Oregon Virtual Academy, said his school had reached peak capacity due to 97 new students enrolling between March 16 — when Oregon’s school closure order first took effect — and March 26. Although their enrollment period typically extends to late April, Sutherland told The 74, “Even if enrollment had not been cut off by the state, we would have had to close it due to reaching capacity earlier than anticipated.”

The executive director of Oregon Connections Academy, Allison Galvin, said that “their enrollment pipeline grew quickly from 700 to 1,600,” but that does not mean all those families were then stymied by the moratorium since, as Galvin said, typically not all families complete enrollment. “Many start just because they are interested in exploring their options and want to find out what it takes to enroll. I will say the families that did enroll in the last few weeks seem to be just very engaged and already finding success with us.”

There was also outcry from virtual education advocates in Oklahoma, where the state closed public schools — including virtual schools — between March 17 and April 6. “We are a state system of public education, and we need to be operating together with a uniform approach and with a unified voice,” said State Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister.

But all Oklahoma schools began administering online instruction this week. Shelly Hickman, an assistant superintendent at EPIC, a virtual charter network in Oklahoma, said that while students will be dealing with increased stress at home, “fortunately we’ll be able to provide them with almost everything we’ve given them prior to the crisis.”

In Pennsylvania, the governor ordered all public schools to close on March 13, and virtual charters, which enroll roughly 37,000 students in the state, interpreted that to mean they could continue operating. The following week, the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators lobbied the governor to place a moratorium on new virtual charter enrollment, with PASA’s executive director telling WHYY he worried how an abrupt loss of funds could hinder brick-and-mortar schools from responding to the pandemic.

So far no moratorium has been issued, but emergency legislation passed by the Pennsylvania legislature on March 25 does say that charter school tuition payments will remain fixed as of March 13, regardless of any additional enrollment.

Ana Meyers, the executive director of the Pennsylvania Coalition of Public Charter Schools, blasted PASA for trying to block families from enrolling in virtual charters. “I think it’s become obvious that a lot of school districts in Pennsylvania were fairly unprepared to continue to educate, and they should not try to prevent the schools that are ready and willing to do so,” she said.

The reports about PASA and Oregon’s funding concerns have led to a flurry of misinformation in subsequent online posts. The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial on March 31 falsely blaming “the Oregon Education Association and its labor allies” for pressuring the state into blocking new virtual charter enrollment. But an OEA spokesperson said the union didn’t lobby state officials on this, and even Sutherland of Oregon Virtual Academy said there was “no unionized uprising.”

On March 26, an analyst at Commonwealth Foundation, a conservative Pennsylvania think tank, accused the Pennsylvania State Education Association (PSEA) of lobbying to block money for virtual charters during the pandemic. It excerpted an email from an unnamed Northeast, Pennsylvania, union leader describing what the union was looking into on members’ behalf, including “how can we prevent mass numbers of students from enrolling in cyber schools.” The Commonwealth writer uses that anonymous email to say that it reveals union president Rich Askey’s “legislative intent.” Later that day, citing the Commonwealth’s post, a columnist for the conservative Townhall news site falsely attributed the email quote about blocking cyber charter enrollment to Askey, not to the unnamed union leader.

Chris Lilienthal, a spokesperson for PSEA, told The 74 the organization was “not involved” in lobbying to freeze charter funding. “We’re comfortable with the provision — it was to provide stability, but it was not something that was at the top of our list,” he said, adding that their focus was on waiving both standardized tests and the 180-instructional-day requirement and ensuring that school maintenance staff had proper protective gear.

For now, many virtual charters have not reported a surge in new students trying to enroll.

“I think most families in this country are really just dealing with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs,” said Hickman, of EPIC. Although students can enroll in Oklahoma virtual schools at any time, Hickman said her network, which enrolls nearly 30,000 students, is not encouraging that, and cited supply chain issues for laptops and other digital resources.

Chandre Sanchez-Reyes, executive director of Indiana Connections Academy and Indiana Connections Career Academy, said her virtual schools are not enrolling any new students this year and “not too many families” have contacted her about fall enrollment.

“It’s not going to be helpful to the school if all of a sudden you take a surge of 1,000 kids,” said Kwitowski of K12 Inc. “Teachers would be overloaded, and it’s not clear all those students will get funded.”

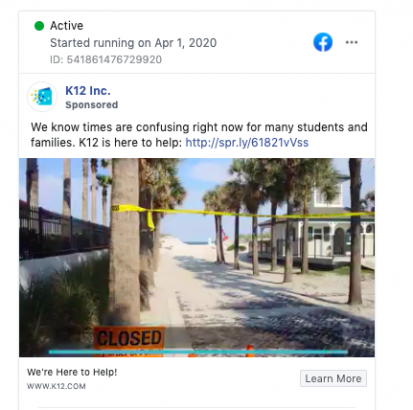

But some virtual charters have been running new ads encouraging sign-ups for their schools. On March 25, Century Cyber Charter School in Pennsylvania launched a new Facebook ad encouraging enrollment for this school year, and on March 30, the Virtual Learning Academy in New Hampshire started advertising, emphasizing that “there is NO admissions process [and] students can enroll anytime.” K12 Inc. has also been running new ads for fall enrollment.

“I haven’t seen a surge, but I’m pretty sure it’s coming,” said Sutherland, whose Oregon Virtual Academy is a K12 Inc. affiliate. “I think a lot of people will want to make a move to where their student can continue without disruption.”

Virtual charter leaders, for their part, are saying they want to use this opportunity to share what they know with brick-and-mortar schools and in no way profit off COVID-19. Many are offering free training and webinars to brick-and-mortar educators and complimentary access to their digital learning tools.

The lines can get blurry, though. One K12 Inc. ad, which launched April 1 and ran for several days last week, linked to a page with both free educational resources and steps to enroll in virtual charters. “We know times are confusing right now for many students and families. K12 is here to help,” the ad says, illustrated with a video montage about coronavirus school closures.

Last week, Sanchez-Reyes co-hosted a webinar advising Indiana charter colleagues on virtual compliance with special education laws, and this week she’s hosting another one on social and emotional learning.

“Most of us came from brick-and-mortars ourselves,” she said, “so it’s been nice to collaborate.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)