Inside the $1 Million Fight to Hold South Carolina’s For-Profit Virtual Charter Schools Accountable

When South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster stepped onto the stage at Charter Schools USA’s annual summit in August, it was to thunderous applause. Alternately smoothing his tie and shielding his eyes from the floodlights, he told a couple of folksy jokes before pivoting to the message he’d come to deliver.

The Rust Belt’s economic losses are the South’s gains, McMaster said, noting how saddened he was by the boarded-up buildings he saw on his trip to Cleveland the year before to nominate Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention. He was sorry about the city’s decline, he said, but South Carolina is booming.

The state needed more charter schools, McMaster told the cheering audience, and he planned to push for laws to make it easier for them to open.

“And I assure you,” he added, “there’s a lot of politics involved often in getting things set up, and whatever politics I can bring to bear is on the side of the charter schools. Wherever we can set them up, we want more, because we know that they work.”

The governor’s enthusiasm is perhaps not surprising. A week before he stepped in to replace Nikki Haley, who was appointed U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, McMaster’s campaign accepted a $2,500 donation from Charter Schools USA, a Florida-based for-profit operator of 70 charter schools.

A month later, there was one for $1,000, followed by an invitation to break ground at the for-profit corporation’s first South Carolina school, located in Goose Creek. A few weeks after the speech, McMaster got a $3,500 check from K12, Inc., the nation’s largest — and arguably, most aggressive — operator of for-profit schools.

South Carolina has been fertile ground for for-profit charter school companies and their trade associations. In particular, online-only virtual schools, like those K12 runs, have taken off in the state, enrolling some 10,000 of South Carolina’s 26,000 charter school students. The largest are publicly traded.

The corporations that run the schools have spent lavishly to ensure the state remains a friendly place to do business. According to South Carolina campaign finance records examined by The 74, seven for-profit school operators and the association that represents them spent nearly $1 million on lobbying and donations to candidates between 2010 and June 2017, the most recent deadline for filing disclosures.

Michael Barbour, an associate professor of instructional design at Touro University California, has written extensively about virtual and for-profit schools.

“I’ve said it many times: When you are operating schools on a business model, they become widgets and the bottom-line thinking becomes, ‘How can I maximize profits for this widget?’ ” he told The 74.

Elected officials, he says, are quick to bite on the notion that free market solutions can be applied to social issues: “Most lawmakers, in all honestly, while ignorant of education policy, figure that since they sat in a K-12 classroom for 13 years, they have some expertise.”

South Carolina’s first virtual schools began enrolling students in 2009, two years after state law was changed to allow the programs.

Just how much political muscle the money translates into is about to be tested. Last year, the organization that oversees the 39 charter schools statewide, the South Carolina Public Charter School District, closed three charter schools, including a low-performing virtual one, S.C. Calvert Academy. The move sent shockwaves through the other underperforming schools that presumably faced a similar fate.

The district also tightened up its expectations for new schools, last year rejecting 12 of 17 applications for new charters. Unless they could find a local school board willing to sponsor them, that meant the programs couldn’t open.

But then in July, a small Christian college with a recent history of financial struggles announced it would begin authorizing charter schools, which by law pay for the oversight. Nine charter schools quickly applied to transfer to Columbia’s Erskine College for authorizing. Three of them are online-only and five are in “breach” status, the last stage before their charter is revoked.

Erskine last week approved all nine schools’ requests to transfer. The state Public Charter School District must now decide whether it agrees the schools should be allowed to change sponsors. Its board is scheduled to take up the requests at a meeting Nov. 9.

Officials at Erskine College declined to comment for this article. “The Charter Institute at Erskine is committed to fairness, transparency and consistency when it comes to school accountability,” its website explains. “We believe that each school’s situation is unique and that the accountability system must value, and not penalize, that uniqueness.”

The schools deny they are “authorizer shopping,” seeking a new overseer that won’t be as rigorous or resetting the clock on a possible closure timeline. Parental choice, their supporters argue, should be the sole barometer of a school’s worthiness.

They are lobbying vociferously against a proposed new Public Charter School District rule that would bar underperforming schools from transferring to new authorizers. But Don McLaurin, chair of the charter district, says forcing failing schools to improve or close is the reason overseers like his nine-member body exist.

“To my mind, which way this goes will have a major impact on whether our mission to have excellent schools succeeds,” says McLaurin. “The law is clear: We must close failing schools.”

‘Overwhelming negative impact’

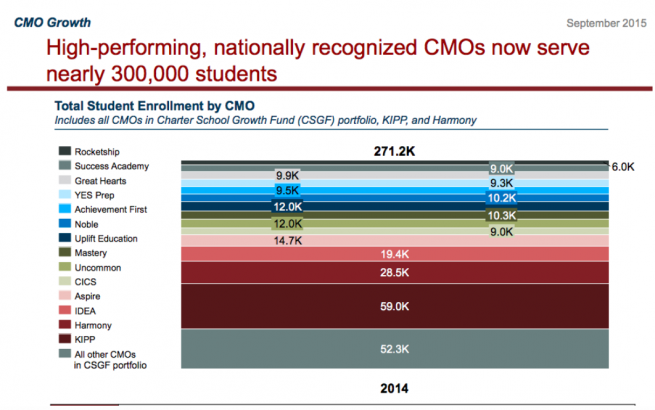

Some 275,000 students are enrolled full time in virtual charter schools nationwide, according to estimates by the digital learning consultancy Evergreen Education Group, That’s more students than are enrolled in high-performing, nonprofit charter networks such as KIPP, YES Prep, Achievement First, Noble, Mastery, Uncommon, Aspire, IDEA, and Harmony schools.

Even the online schools’ staunchest critics say there’s a place for them. They cite students with chronic illnesses or with mental health issues, students whose involvement with sports or acting means they travel a lot, and other unique circumstances. But most students don’t succeed in the schools.

Almost all of the research on virtual schools documents dismal results. In the most definitive examination, in 2015 the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, better known as CREDO, found the schools have an “overwhelming negative impact” on student growth.

Full-time online students, researchers found, on average made no progress at all in math and were the equivalent of 72 school days — almost half a year — behind their peers in reading.

Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, was one of the researchers behind the report. She says one striking element is how little time virtual students spend with their teachers.

“When we looked at how much instruction kids were getting with an actual teacher, there was just very, very little time with teachers,” she said. “If they disengage, it’s generally just on them and their parents.”

About 1 in 2 South Carolina virtual school students who start each school year stays enrolled to the end of the year, according to a June story in The Post and Courier of Charleston. Fewer than half of students graduate on time.

A school’s nonprofit status matters, too. Earlier this year CREDO found that students in charter schools run by for-profit companies lag behind students in both traditional district and nonprofit public charter schools. The same research found that nonprofit charter operators have a substantial, positive effect on learning, particularly for low-income students of color.

Lake says there is a place for high-quality virtual schools that can serve students who for whatever reason can’t physically attend school. States need to consider creating a separate set of rules governing online schools and encouraging potential nonprofit providers to innovate, in her opinion.

One example: Space permitting, charter schools must admit any applicant. Virtual schools would benefit from rules requiring them to identify and limit enrollment to students who are likely to do well.

“The results from CREDO are so strikingly bad — I don’t know how else to say it — it’s worth noting which kids can be successful because most cannot,” Lake said. “If these are going to be charter schools, our strong recommendation is you treat them as unique.”

Last year, a joint report by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, the national education advocacy organization 50CAN, and the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools outlined a series of recommendations for ways states can hold virtual charter schools accountable for student academic growth.

Online schools should be required to screen students to make sure they have the capacity or support to work independently and should receive funding based on student results, such as number of graduates or students who completed a meaningful amount of work, the report suggested.

Expect more virtual schools

In 2015, 31 percent of South Carolina fourth- and eighth-graders scored at grade level or above in math and reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Only nine states had lower scores on the test, often referred to as the nation’s report card. Although the state’s schools graduate more than 80 percent of students, their average composite score on the college-placement ACT exam is 18.5 out of 36, which ranks 48th in the nation.

Concerned about quality in a number of its charter schools — both online and brick-and-mortar — the board of the South Carolina state charter district four years ago implemented a new accountability framework that held schools accountable for a number of factors, including student academic growth. The framework is based on policies identified by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers that were successful in other places.

As a part of that process, the charter district hired a new superintendent, Elliot Smalley, who is a veteran of other efforts to raise quality in lagging schools. Prior to moving to South Carolina, Smalley was chief of staff for the Tennessee Achievement School District, a state-run attempt to lift the lowest-performing 5 percent of that state’s schools.

He says the new system for assessing school performance was created after consulting with South Carolina’s charter schools.

“I might also add that we built our performance framework with our charter school leaders over the course of six months — we held visioning meetings with them, surveyed them, and got feedback in multiple ways,” Smalley said. “Several of the new measures — for example, growth, off-cohort graduation (e.g. fifth-, sixth- and seventh-year graduates counted equally), and a school-specific indicator — are weighted heavily and directly reflect their feedback.”

The charter district has compiled and released results for the framework’s first three years. None of South Carolina’s five virtual schools are in good standing with the charter district. State law mandates the closure of charter schools scoring in the lowest tier of performance for three consecutive years.

The charter district’s framework uses data from the state’s accountability system, but includes other performance measurements. South Carolina’s school ratings system has been on pause for the past two years while new state and federal policies are settled.

The three schools in “breach” status in the charter district’s system, the rung right before closure, contract for management services, curriculum, and other aspects of day-to-day operations with the corporation that has spent the most money lobbying. South Carolina Virtual Charter School, with 3,300 students; Cyber Academy of South Carolina, with 929; and Odyssey Online Learning, with 528 students, all contract with K12.

The head of school at Cyber Academy of South Carolina, David Crook, says unhappiness with the state district extends beyond the virtual schools to the larger charter school community. Under state law, the authorizer functions as the schools’ district, responsible, he says, for such things as providing technical assistance to schools looking to improve. The charter district’s new leadership, he asserts, has focused on its accountability framework to the exclusion of its other functions.

“We’re all kind of in the same boat,” Crook said of the schools seeking to transfer away from the state district. “With the new administration that’s come in, it’s a different district.”

Since opening its first school in the state, K12 has spent $470,456. The lion’s share, $403,000, paid for lobbying. Campaign contributions from the publicly traded concern went to three governors, four political party units, and a Who’s Who of legislative leaders, including Senate Finance Committee Chair Hugh Leatherman Sr., whose committee is one of those that must approve the charter district’s funding, and veteran lawmaker John Courson, who was suspended from the state Senate after being indicted in March on charges of converting campaign funds for personal use.

K12’s flagship virtual school spent $80,000 lobbying. Another national virtual operator, Connections Academy, spent $96,416, almost all of it on lobbying. Brick-and-mortar for-profit school operator Edison Learning spent $172,291, mostly on lobbying. And the South Carolina Alliance of Public Charter Schools, a trade association, has spent $61,293.

Added to smaller amounts spent by newer education management organizations, and the total is $926,056, of which $84,000 went directly to the campaigns of public office holders. Some of those elected officials, such as Gov. McMaster and Sen. Leatherman, who is also the Senate president pro tem, appoint the board members who oversee the statewide charter district.

Spending has been similar in other states where K12 and Connections enroll students, including Pennsylvania, Colorado, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Indiana. State laws notwithstanding, efforts to close failing virtual charter schools in some of those states have failed.

In one instance, parents sued to keep an underperforming cyber-charter school open in Tennessee. In Indiana, state overseers took no action against a K12 school that had earned Fs for six consecutive years — two more than the law says merits closure. Overseers have been trying to address problems at Nevada Connections Academy for nearly two years.

According to a 2016 investigation published by Education Week, more than $14.5 million in lobbying activity by online for-profit charter operators has taken place in states where the spending must be disclosed. The publication additionally reported that K12 brought in some $873 million in fiscal year 2015, 80 percent from schools it managed. Officials with the $5.5 billion conglomerate Pearson, which owns Connections, would not say how much revenue its cyber schools generate.

During the same time period, South Carolina virtual schools have received more than $350 million in taxpayer money, the per-pupil expenditures that follow students to whatever school they attend, according to The Post and Courier.

K12 Inc. declined to comment for this story, noting that the decisions to seek a new sponsor was made by the South Carolina schools’ boards, which are independent nonprofits by law. Connections Education supplied a similar response, also noting that South Carolina Connections Academy, with which it contracts, is not seeking to shift to a new authorizer.

On October 27, K12 announced it had named prominent school choice advocate Kevin Chavous as president of academics, policy, and schools. A former Washington, D.C., city council member, Chavous has worked with both the American Federation for Children, the advocacy group chaired by Betsy DeVos before she was appointed U.S. education secretary, and Democrats for Education Reform.

Chavous’s hiring comes at the same time that DeVos has championed the expansion of virtual schools from her Cabinet post, as she did when she was running AFC.

“I expect there will be more public charter schools. I expect there will be more private schools. I expect there will be more virtual schools,” DeVos told Axios a week into her tenure. “I expect there will be more schools of any kind that haven’t even been invented yet.”

Chavous’s appointment was also celebrated by a social media network that promotes virtual chartering under the hashtag #ITrustParents. South Carolina is just the most recent place where Public School Options, the group responsible for the social media campaigns, has come to the defense of failing virtual schools. It, too, has a Washington, D.C., address.

‘Moms like me’

In October, Public School Options supporters packed the usually sedate meeting of the South Carolina charter district board, where board members for the second time took up the topic of whether to pass a proposal spelling out how it should handle requests from schools in poor standing that want to transfer to a new charter authorizer.

Board chair McLaurin reiterated numerous times that South Carolina law is clear in tasking the board with creating new forms of accountability for schools and with not tolerating poor performance.

Public School Options has been organizing around the issue for nearly a year. A member of the group’s board, Colleen Cook, blogged about the need to raise understanding about the state board’s quest to increase standards last fall.

“Raising awareness about this framework is vital because the parent perspective is so important in the fight for more, not fewer, school choice options,” she wrote. “And if the South Carolina Charter School District continues on its current path, the reality is that there will be fewer options in the future for South Carolina students — options that have worked for moms like me.”

Public School Options’ South Carolina chapter had harsh words for the board in formal comments to the proposed new rule. The Board’s “fixation on the universal adoption of some set of rigid ‘national industry’ standards in Sponsor policies is exactly what the Legislature was trying to move away from in the creation of the Charter Law,” the comment asserted. “It certainly has been noted by South Carolina parents that while no particular effort was made to reach out to those of us here in South Carolina most directly impacted by these rules, the [district] staff did reach out to national interest groups in an attempt to manufacture comments in support of its pre-conceived notions.”

Smalley disagrees, saying he sees pushing accountability as fighting for families: “Opponents of accountability are very clever about propping up a few vocal parents to deliver their talking points, but we know that the silent majority — tens of thousands of South Carolina’s parents — desperately wish for high-quality, accountable schools.”

Nor does he think Public School Options’ characterization is fair, Smalley says.

“Specific to the question of standards and best practices, I think three things are really important here,” he continues. “One, the word ‘standards’ can be easily confused — our performance framework is built on South Carolina assessments, not any national learning standard.

“Two, I believe that kids and families benefit when educators learn and share proven practices — and in South Carolina, where the majority of kids can’t read, write, and do math on grade level and where we have centuries-old inequities, it would be unconscionable not to learn from others.

“And three, when it comes to following standards for quality authorizing, our state law commands us to do this,” Smalley concludes. “From the law itself: ‘(A) In order to promote the quality of charter school outcomes and oversight, the charter school sponsor shall adopt national industry standards of quality charter schools and shall authorize and implement practices consistent with those standards.’ ”

Separately, proponents of unregulated choice accused the state board of having become a bureaucracy.

Similar social media campaigns have happened in other states where authorizers have attempted to address poor virtual school performance. Frequently the parents have been brought together by Public School Options, a 501(c)(4) organization that does not have to disclose its funding sources.

Public School Options spends about $2 million a year organizing parents and promoting unfettered school choice, according to its IRS nonprofit disclosures. The money is evenly divided between recruiting and training parent advocates, “educating lawmakers about need,” and engaging the media.

It was launched by Midland Strategies, a political consulting firm based in Iowa and Washington, D.C., that was started by the former Iowa Republican Party chairman. Until recently, the chair of Public School Options’ board and head of the South Carolina chapter — composed of virtual school parents — was Beth Purcell, who also has served on the board of the South Carolina Connections Academy.

Test scores, its social media campaigns posit, are not a reliable measure of a school’s value.

Early this fall, state Sen. Leatherman appointed Purcell to the public charter district board. At that point, she had already left her position as Public School Options’ chair. She has opposed the proposed transfer policy, saying at at the board’s September meeting she did not agree with a “blanket statement” about denying schools in breach freedom to transfer.

She did not respond to The 74’s request for comment.

On Halloween, Purcell took to Twitter to thank Gov. McMaster for his support: “Delivering a Halloween treat to a very special First Dog this afternoon!” she wrote.

A June 2015 Facebook photo shows her celebrating in front of K12’s ticker at the New York Stock Exchange.

https://www.facebook.com/PublicSchoolOptions.org/photos/p.10153456341284577/10153456341284577/?type=3&theater

At the national level, school accountability proponents, who have participated in efforts to raise standards for virtual schools, note that parent demand, not corporate lobbying, is often what elected officials cite when justifying allowing a failing cyber school to stay open.

It’s unclear whether Purcell’s appointment is the first sign that a political noose is being tightened around the charter district’s drive for higher standards. Since Erskine agreed to accept all nine of the schools seeking new oversight, the charter district must now decide whether to sign off on the moves. Accordingly, the adoption of the transfer policy was tabled until January.

The board did revise the proposed policy saying underperforming schools won’t be allowed to seek a new sponsor, Cyber Academy’s Crook said. The latest version would take multiple factors into account when deciding whether a school should be allowed to transfer.

Even so, it’s not the agreement under which the schools opened, he adds. “What I’ve always believed is that my school and other charter schools should be held accountable to the terms of their contracts,” he says. “There’s no clear rubric.”

McLaurin disagrees. The board’s mission statement, he reminded those at the October meeting, “says improve student learning. It does not say preserve the status quo.”

“Our job is to establish new forms of accountability, and this state badly needs new accountability,” he added. “I’m just gonna tell you, when you start striving for excellence, you start to get pushback. The status quo is much easier.”

In Smalley’s view, South Carolina has some outstanding charter schools that should serve as examples of what’s possible.

“There is a huge gap between this future vision and where we currently stand,” he said. “Today, we remain a choice system marked by inequity, inaccessibility, and uneven results. We have huge achievement gaps by income and race. And while we have some high-flying charter schools that inspire hope and deserve to be replicated statewide — something we’ve prioritized — we have others that are failing students and ripping off taxpayers.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)