College Promise Programs Add a ‘Higher Promise’ of Jobs Along with Scholarships

Paying for college isn’t always enough to improve students’ lives, so promise programs now connect students to internships and apprenticeships too.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

College promise programs offering “free college” to local students are increasingly adding a new task to their core mission — connecting young people to internships and apprenticeships.

The programs, in which students are promised free college tuition if they graduate high school, have long been considered a silver bullet against the soaring tuition and loan debt blocking many young people, particularly those who are low-income, from earning degrees and finding fulfilling careers.

But in the last few years, college promise programs from Kalamazoo to New Haven, Buffalo, Detroit and Columbus, Ohio, have realized that paying tuition alone doesn’t always achieve the ultimate goal of making lives better. So they have added staff and built partnerships with business to start internship, mentorship and apprentice programs that give “promise scholars” a start on career paths.

Further highlighting the shift, college promise advocates nationally will hold their fourth College Promise Careers Institute Nov. 8 and 9 at the University of Tennessee. U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona and First Lady Jill Biden will speak at the event, whose major topics include “Empowering Career Exploration and Pathway Discovery” and “Building the Promise Pipeline of Workers.”

“We’re quick to say ‘Go to college, get your degree,’ but you don’t have that follow up piece of what do you do after that?” said Jade Scott, who works with the Detroit Promise through the Detroit Regional Chamber of Commerce Foundation. “So many students get lost in the shuffle, like ‘I’m done with my degree, what do I do now? And this is where we really come in.”

“Now, we’re talking about how we get them employed,” Scott added. “What are we doing to support you, as you make that journey from these college classes into an actual career that you genuinely enjoy, or that’s making you money, or that’s offering you a sustaining lifestyle?”

Detroit Promise, with the help of the chamber, gave 450 students work experiences such as internships or job shadowing in the 2022-23 school year, Scott said.

The Kalamazoo Promise, perhaps the best-known promise program in the nation, considers the internship program it launched in 2022 so important it calls it “Higher Promise.”

Cetera DiGiovanni, Higher Promise coordinator, said parents previously kept asking if Promise officials knew of open jobs while businesses repeatedly asked the program for help finding talent.

“We know that kids are graduating and no one has jobs,” DiGiovanni said. “We thought we would be the mediator to bring them together.”

David Rust, executive director of Say Yes Buffalo, said the evolution is natural. Say Yes Buffalo, which started as a scholarship program in 2011, placed 25 students in apprenticeships in the fall of 2022 and another 25 this year.

“It stands to reason that there will be refinements, expansion of features, because we know a lot more now about what scholars and students need,” he said.

College promise programs began in the 1990s with individual philanthropists adopting single schools and pledging to cover college tuition for any student that graduated from high school and enrolled in college. Anonymous donors in Kalamazoo started a citywide promise program in 2005, then other promise programs like Say Yes to Education expanded from single schools in the 1990s to the cities of Syracuse and Buffalo, New York, Greensboro County, North Carolina, and finally Cleveland in 2019.

States like Tennessee have also added statewide promise programs as the ranks have swelled to more than 400 programs nationally. The programs differ in what colleges they pay for, with some covering only the local community college, some only in-state public colleges and others including private universities that choose to be partners with them.

But once lauded for wiping out the worries of tuition debt, promise programs have found that students, particularly low-income students, also need chances to test drive careers they think they might like. They need mentors in their field. They need workplace experience before graduating and seeking a full-time job.

Sometimes students simply need a paycheck while they are in school to pay for rent, commuting to class and meals, which promise programs rarely cover. Or they skip college altogether because class time takes away earning time they need to help their families.

“Free college can be too expensive for students,” said Rust. “A lot of our scholars, over 50 percent, have combined family income below $40,000. So, we’ve seen this more so than ever throughout the pandemic, you (students) do what you have to do, not necessarily what you want to do.”

There’s also benefit to the regional economy when students find careers that keep them in the city after college.

In Columbus, Ohio, where a pilot promise program pays for Columbus school district graduates to attend Columbus State Community College, companies such as Nationwide Insurance and gas and electricity supplier IGS Energy are eager to take on promise students in college as paid interns.

John Wharton, 19, a second year finance student at Columbus State, started work at IGS this fall helping manage and audit customer accounts for $18 an hour. Because he has an interest in marketing too, his supervisors are also trying to find chances to work in that department.

“It gives you a sense of feeling for what the real world is,” said Wharton, who had never had a job before the internship. “This gives people a platform to gain insight, whether or not they actually want to do what they’re studying.”

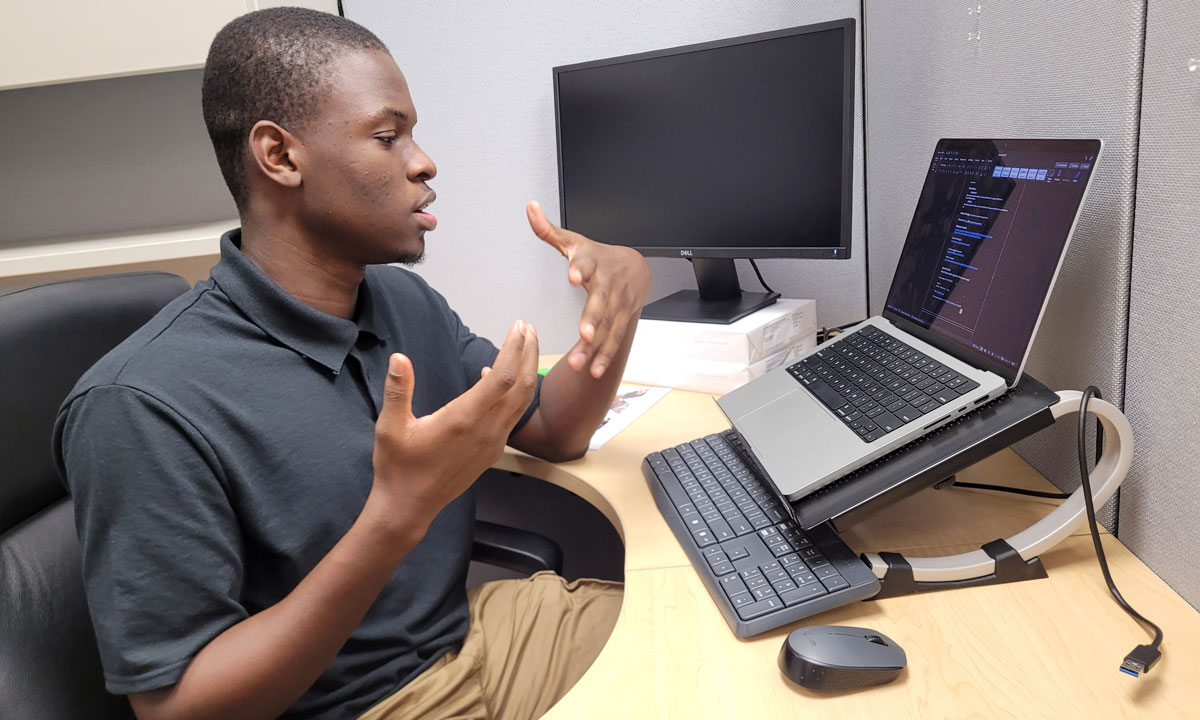

Abdallahi Thiaw, 20, also a Columbus Promise student, also just started as an intern this fall with the Workforce Development Board of Central Ohio for $20 an hour for 20 hours a week. Since he is earning an associates degree in interactive media, developing apps and programs that can be used on mobile devices, the board has him developing a chat program for its website that lets users find out what services the nonprofit provides.

“It’s a big opportunity for students like me, because a lot of job fields will tell you that once you graduate, you need experience,” said Thiaw. “But the main issue is nobody’s offering experience, so how are you going to get that experience? But with this program, it offers students like me experience and on top of that, you get paid great wages, which really helps us in focusing on school.”

David Campbell, director of communications for the board, said matching students with work that fits their interest, like is happening with Thiaw, is ideal.

“That idea is the genesis of this program, that they need to work, they need to have some money, but it needs to be earned and still learn, right?” Campbell said. “It has to combine with their degree, so they get someplace at the end of it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)