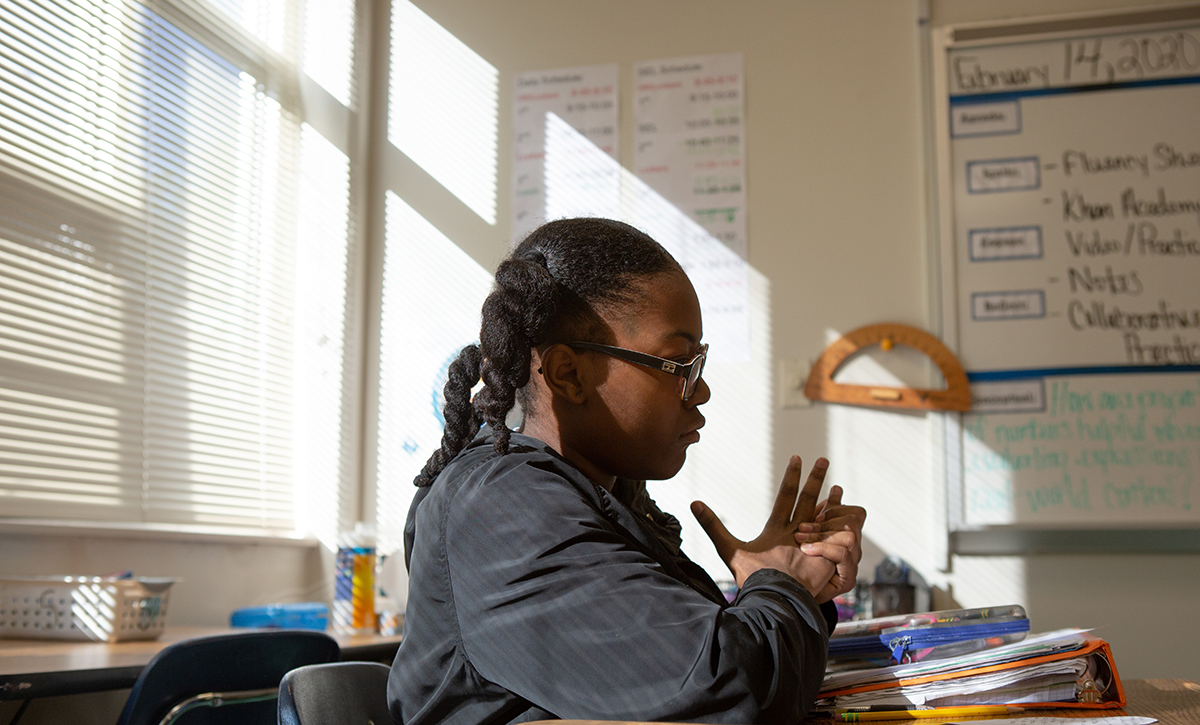

Nashville Study Finds Major Disconnect Between Black Girls and Mathematics

Black girls were far more likely than Black boys to have 'a negative math identity' and to not see how the subject connects with their future.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A study of Nashville high-schoolers exposed an alarming disconnect between Black girls and mathematics, one that might explain their lack of confidence in the subject — and why they don’t see how it can help them achieve their professional goals.

More than 70% of Black female respondents in general math classes had “a negative math identity” compared to 14% of Black boys. And 86% of Black girls in general math did not see the connection between their desired careers and mastery of advanced mathematics — even when they wished to enter STEM fields. That is compared to 67% of Black boys.

“What students believe about math — and their ability to learn math, to be good at math — is really important, both in the moment and in the long term,” said Ashli-Ann Douglas, a research associate at WestEd, a San-Francisco based national nonprofit. “And those beliefs are related to the quality of math instruction that they receive.”

Douglas was the lead researcher on the report when she was a graduate student at Vanderbilt University. The 251 students in her study — 83% were in the 11th grade and 17% had been retained at some point and were in 10th grade — participated in fall 2019. One child had skipped a grade and was a high school senior.

More than 80% of respondents were Black: 78% lived in a home with an annual household income of less than $50,000 while more than a quarter lived in a home with a household income of less than $20,000.

Pamela Seda, president of the Benjamin Banneker Association, which works to empower Black children by boosting their access and success in mathematics, said there are two stereotypes at work here: that Black people are not gifted in mathematics and that girls in general struggle with the subject.

“When you put those stereotypes together it compounds the negative effects,” she said.

Shelly M. Jones, a mathematics education professor at Central Connecticut State University and member of the National Council for Teachers of Mathematics board of directors, said math curriculum is often not culturally relevant.

Jones, in teaching graduate students, highlights the work of trailblazer Gloria Gilmer, an expert in ethnomathematics, the study of how math is used in different cultures.

One of Gilmer’s papers examined the math behind African-American hairstyles. It was, Jones said, a transformative lesson: One of her Black female students told her Gilmer’s work made her feel recognized in the topic for the first time.

“Black girls don’t see themselves in mathematics,” Jones said. “The things that they like, they don’t see in math.”

Douglas, the researcher, found that 99% of respondents considered basic math — number and operations skills — to be useful while only 58% said the same of higher level math, including algebra and statistics. The study, published earlier this month in the American Educational Research Journal, helps explain why the nation is missing out on the talents of many underserved students, she said.

“This is one of the ways we lose out on the genius of young people,” Douglas said. “Math is a gatekeeper in a lot of ways: When students do not have the math skills they need to access different careers, that is a barrier. And when they don’t have the beliefs about the utility of math, the value of math, they are less likely to persist and advocate for improved quality of instruction.”

Douglas’s paper also revealed that 29% of Black boys said their teachers’ recognition or acknowledgment of their performance in class was an indicator of their math proficiency.

None of the Black girls said they received such positive feedback.

Black students also did not believe their teachers were adequately prepared to teach the subject, regardless of their credentials, the study notes. And Black girls were more likely to cite their own poor understanding of math as a sign that they were not good at the subject.

Students’ personal testimony was powerfully revealing, researchers said.

“He doesn’t know how to teach in a way that people understand,” said one student in a focus group. “He doesn’t know how to teach right.”

The result was devastating.

“I’m failing now,” the student said. “I never failed last year. I’m failing this year.”

Researchers noted that several students described that same teacher as “nice,” indicating the issue was not about personality, but effectiveness.

Douglas said her findings emphasize the need for more inclusive and equitable math teaching methods to help marginalized students — particularly Black girls.

Even with the required credentials to work in the field, teachers need ongoing coaching to help them work with students and relay the importance of the subject in their lives, she said.

She and others from her research team spent a few hours leading a districtwide training shortly after the study was conducted, providing hands-on lessons for educators in the summer of 2021. In addition, 10 educators, including teachers and their advisors, subsequently completed a semester-long coaching program led by Douglas and her team.

Douglas’s report is part of a larger longitudinal study of math knowledge development that started when the students were in preschool: The children were recruited in 2006 from 57 pre-kindergarten classes at 20 public schools and four Head Start sites and were followed through high school.

Kelley L. Durkin, research assistant professor in the department of teaching and learning at Vanderbilt, and Bethany Rittle-Johnson, a professor of psychology and human development at the university, oversaw the last phase of the project, which wrapped up in 2022.

Rittle-Johnson said she was surprised when some students said their math teachers refused to help them or shamed them for not paying attention.

“All the students in our focus groups valued their education, but they did not all receive the quality of math instruction and support that every student deserves,” she said. “Inequitable access to resources for both students and teachers have serious consequences for students’ learning opportunities, and it is not fair nor just.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Overdeck Foundation provide financial support to WestEd and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)