Push to Remedy Grossly Unequal Suspensions of Black Girls After Sweeping Report

GAO study reveals that not only are Black girls removed from class more often than white girls but for similar behaviors in the same schools.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

“Discipline for Black girls isn’t set up for the person being disciplined to explain themselves. It was more so just assumed that the person was in the wrong.”

“During my time in school I noticed that some of the Black girls would get in trouble for dress code even though their peers of a different body shape would not get in trouble for wearing the same thing.”

“From being in school, it always seemed to me that Black girls were always the ones who got disciplined. Not saying White girls never got disciplined, but maybe they were given a little more wiggle room for error unlike the other Black girls.”

These were some of the observations young women shared with the researchers of a new U.S. Government Accountability Office report, which found that Black girls in public schools face more and harsher forms of discipline when compared to other girls. While it’s long been known that Black female students are disproportionately punished in school, the GAO report determined that removals from class were happening to Black girls for similar behaviors as white girls and in the same schools. This points to the disparity being more about how Black girls are treated in school than how they act.

“This damning new report affirms what we’ve known all along — that Black girls continue to face a crisis of criminalization in our schools,” U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley said at a press conference last month unveiling the findings. “And the report provides powerful new data to push back on the harmful narrative that Black girls are disciplined more because they misbehave more.”

Pressley, a Massachusetts Democrat, is hoping the GAO report that she commissioned with House Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi and fellow congresswoman Rosa DeLauro can drive a legislative remedy to end racial disparities in the disciplining of Black girls. She told the Dorchester Reporter in late September that she realizes the Ending PUSHOUT Act, a bill she re-introduced in April, stands little chance while Republicans control the House, but that states can take the findings and move on their own to address the inequity.

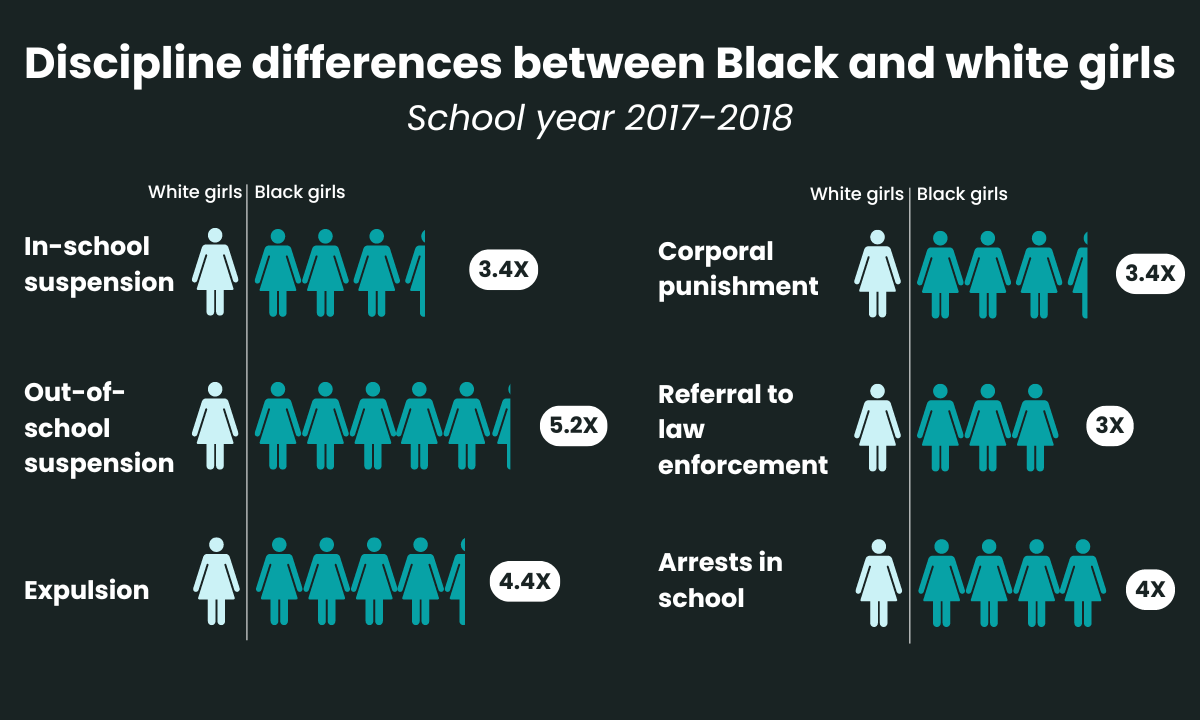

While Black girls represented 15% of all girls in public schools, they received almost half of all suspensions and expulsions during the 2017-18 school year, including 45% of out-of-school suspensions, 37% of in-school suspensions and 43% of expulsions.

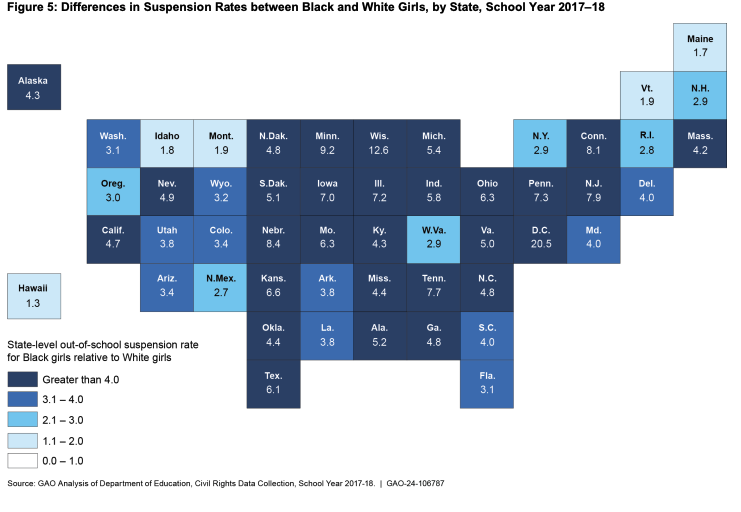

Black girls received exclusionary discipline at rates 3 to 5.2 times that of white girls. This pattern held true in every state and most drastically in the District of Columbia, where the out-of-school suspension rate for Black girls was 20.5 times the rate for white girls. These disparities were felt even more harshly by Black girls with disabilities, who were more likely to be removed from school than both Black girls without disabilities and white girls who were also disabled.

Exclusionary discipline can result in both short- and long-term negative outcomes for students, according to the report, the first, according to the congresswomen, to directly analyze not only disciplinary outcomes but also the preceding behaviors.

While previous GAO work demonstrated racial disparities in K-12 discipline, a dearth in data meant that researchers couldn’t establish whether that inequity remained across similar behaviors. This time, though, researchers were able to use an additional national data set — the School-Wide Information System — which tracks infractions and associated discipline across 5,356 schools in 48 states alongside U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data.

This filled a “big gap in the research,” according to Jackie Nowicki, the report’s lead researcher and a director on the GAO’s Education, Workforce, and Income Security team. “That was huge for us,” she said, “because — as far as we know — that kind of research has never been done before.”

Nowicki said she hopes people will understand the results are, “not an opinion. It’s not a hypothesis. This is serious, robust, objective, non-partisan analysis from nationwide data.”

The report also included an analysis of 26 empirical studies, data from the National Crime Victimization Survey and 31 responses to an anonymous questionnaire circulated to women ages 18-24 this year by the national organization, Girls Inc.

Through this work, researchers identified multiple forms of bias that contributed to discipline disparities, including colorism and adultification, a form of racial prejudice in which kids of color are perceived as older, less innocent and more threatening. One study included in their review found that Black girls with the darkest skin tone were twice as likely to be suspended as white girls, which didn’t hold true for Black girls with lighter skin complexions.

Researchers also found that Black girls reported feeling less safe at and connected to their schools than their peers, factors which can impact both attendance and academic performance.

Amid a mental health crisis that is harming young girls in particular, “this is a really important piece of that overarching picture about how girls see themselves, how they experience the world, and what they take with them into their [adult] lives after they’ve left K-12 school settings,” Nowicki said.

To combat these issues, Pressley’s legislation would provide grants to states and schools that commit to banning discriminatory discipline practices, work to strengthen the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights and establish a federal task force to study and eliminate these practices.

Rohini Singh, director of the School Justice Project at Advocates for Children of New York, said she is optimistic that with increased awareness from reports such as this one, those on the ground, like school deans or administrators, will “check themselves” before doling out consequences.

The report will also be helpful in implementing solutions, she said. Often in New York she hears debates about how to keep schools safe: “What that means for a lot of people is more police in schools, more discipline, more suspensions. It’s becoming clearer through reports like this — and data that we have — that that’s not necessarily the case … oftentimes students can feel less safe because they can be targeted.”

Nowicki shares Pressley’s skepticism that the necessary action will happen at the federal level and her hope that the report can drive reforms locally.

“The kind of change that needs to happen here is going to happen school by school, building by building, individual by individual, by people who realize that this is a systemic issue shown in the data, and that we all can be part of this solution if we choose to be.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)