As It Closes In on 20 Years, IDEA Public Schools, Texas’s Homegrown Charter Network, Is Big, Bold and Sticking to the Basics

By Bekah McNeel | May 12, 2019

Updated May 14

Weslaco, Texas

A handful of high schools from the Rio Grande Valley repeatedly appear among the most challenging high schools in the nation. Such distinctions seemed improbable in 2000 when JoAnn Gama and Tom Torkelson applied for a charter to open up a new elementary and middle school in the region.

Nineteen years and 45,000 students later, the fast-growing network and its tough-talking leadership have garnered both accolades and resistance, being dubbed both a “Bright Spot in Hispanic Education” by the Obama White House and a “Texas Sized Destroy Public Education IDEA” by anti-charter advocates.

To all the skeptics, the network answers with results: 100 percent college acceptance rates in schools where at least 85 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch. Students passing an average of three AP exams before graduation. Parents want it. Foundations want to fund it.

The U.S. Department of Education has shown similar enthusiasm for IDEA, awarding it $117 million in the 2019 round of charter school expansion grants announced earlier this month. It was the largest award given in the grant’s history.

From its inconspicuous headquarters in Weslaco, Texas, on the border with Mexico, IDEA is becoming one of the most recognizable names in the national charter landscape. Now with nearly 20 years of experience, its founders say they plan to stick with the philosophy that got them here.

What’s the big IDEA?: What’s the big IDEA?

The network is growing at blinding speed, applying for expansion after expansion to their original charter with the Texas Education Agency. What began in 2000 as 150 fourth- through seventh-graders in Donna, Texas, has grown to 79 schools and 45,000 students throughout Texas and Louisiana, with plans to expand into Florida in 2021.

The network’s co-founders, Torkelson, the CEO, and Gama, the superintendent, were inducted into the National Charter School Hall of Fame in 2018, and the network won the $250,000 Broad Prize for Public Charter Schools in 2016, given to the network that has done the most to boost student outcomes, close the achievement gap and increase graduation rates.

“[Enrollment] will reach 100,000 students by 2022,” Torkelson said. This would make IDEA the fifth-largest school district in Texas. He thinks it’s realistic to expect that number to double by 2028. In a recent interview, the 44-year-old quipped that he has at least 30 more years in him and would like to see enrollment hit 1 million by the time he retires.

IDEA frames its growth in competitive terms. While some charter networks file expansion applications by referencing zip codes or counties, IDEA is among those that list the school districts where it plans to operate. They aren’t the only network to put districts on notice, but they are the most prolific.

Such ambitions, articulated with Torkelson’s frank delivery, have raised the hackles of district administrators. In September, two area superintendents and the local teachers union unsuccessfully petitioned the San Antonio City Council to disincentivize the charter network’s growth by not allowing IDEA to claim tax-exempt status for a $220 million bond issue.

The Rivard Report’s Emily Donaldson reported that “City CFO Ben Gorzell said this is the first time he has seen traditional school districts weigh in on this ‘very narrow procedural approval.’”

In public hearings and interviews, superintendents and union representatives characterized IDEA’s growth as detrimental to public schools.

“If you vote in favor of this, you’re supporting the expansion of privately run charters, and further diversion of funds from our public school districts and the children they serve,” said Shelley Potter, president of San Antonio Independent School District’s union. “You will be helping IDEA to expand their privately run, unaccountable school district.”

As school districts in El Paso braced for the arrival of IDEA — spurred in part by a nonprofit headed by Amy O’Rourke, wife of presidential hopeful Beto O’Rourke — Socorro ISD Superintendent José Espinoza told the El Paso Times, “I tell the team — our assistant principals, principals, the board — that we’ve got to step up our game. They’re going to try to take our kids.”

Public showdowns aren’t necessarily new to IDEA, but neither are they something Gama and Torkelson would necessarily have imagined 20 years ago. Especially not conflict over rapid growth strategies. It took seven years for IDEA to launch its second campus. In fact, Gama explained, they had not originally envisioned going beyond fourth through eighth grades.

“Parents really made a pitch and compelled us to start a high school,” Gama said. Then a group of lower elementary parents approached them, Gama explained: “They said, ‘If you can do it in high school, you can do it in elementary.’”

The first school grew as families drove to Donna from Raymondville, La Joya and other tiny towns in the Valley with small independent school districts. In 2005, demand reached the point that opening a second and third school seemed viable. It was. A three-year, $3.5 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2009 accelerated their growth, and there are now 23 IDEA schools in the Rio Grande Valley.

At the invitation of the Brackenridge Foundation and San Antonio Spurs legend David Robinson, IDEA moved into San Antonio in 2012. Robinson wanted to convert his private Carver Academy to a charter school.

“We get to be the beginning of an incredible movement,” Robinson said seven years ago. “We at Carver will be the first in a line of schools that will transform San Antonio.”

The growth in San Antonio has been prolific, with many of the city’s major philanthropies sponsoring new campuses. National philanthropies and the U.S. Department of Education also invested in IDEA, speeding its growth. As of 2017, IDEA reported the following lifetime giving totals: Texas Education Agency — competitive grants to fund program innovation: $12.8 million; Charter School Growth Fund: $12 million; Ewing Halsell Foundation: $10 million; Michael and Susan Dell Foundation: $7.7 million; Walton Family Foundation: $5 million; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: $4.3 million; Brown Foundation: $1.5 million; George W. Brackenridge Foundation: $1 million; and KLE Foundation: $17.9 million.

The big figures fuel expansion, Torkelson explained, but not operations. Once a school is opened, it becomes self-sustaining. New buildings and school leader residencies are the primary cost drivers of expansion. Charter schools do not have access to public funds for the full cost of facilities in most states, including Texas. To ensure consistency across the brand, future school leaders spend one to three years in a “principal in residence” program at a school in one of IDEA’s largest markets — the Rio Grande Valley, San Antonio or Austin.

The million-dollar figures and fast pace look aggressive, Torkelson said, but it’s based on demand. “I don’t ever hear parents on our waitlist saying we’re too aggressive,” he said.

In 2012, he and Gama learned a lesson when they contracted with Austin Independent School District to operate one of the district’s struggling campuses. Protesters eventually killed the deal.

From then on, Gama said, they never considered a new city until parents invited them in, as they have in El Paso, Fort Worth and Baton Rouge. When IDEA came back to Austin in 2013, they did so at the request of interested parents and philanthropic backers, not a struggling school district. That model of growth continued to work. In 2019, IDEA is set to add four more schools in Austin, for a total of 14.

IDEA thrives where school choice has been lacking, Gama said: “I don’t think that anybody knew what a charter was in the Valley.”

At the same time, families in the Rio Grande Valley have had access to some form of school choice far longer than most parts of Texas and rest of the United States. South Texas ISD, a public school district that overlays five other Rio Grande Valley districts, was founded by the Texas Legislature in 1964 to offer alternative high school choices for students with learning differences. It has evolved into a series of magnet high schools for advanced learners.

There were no such choices for elementary school children or children who were not already identified as high-performing.

The opposite is true too, Gama said. Where school options increase — such as they did in San Antonio, where charters are booming and the San Antonio Independent School District launched its own choice schools, partly to compete — they see their waiting lists shrink.

Gama says she’s not bothered. It’s more options for families, and that, she said, is the whole point.

Parents know what they’re getting: Parents know what they’re getting

While Torkelson is often the public face of IDEA’s growth — known for boldly saying in public what many would only say behind closed doors — Gama is considered by many to be the taproot of IDEA.

Her eye is on brand loyalty. Parents love IDEA, she said, because “they know what they are getting.”

The engine that runs IDEA Public Schools is fairly basic — at this point in 2019 it almost qualifies as vintage. Its “college for all” and “no excuses” model has gone out of fashion in many markets. However, rather than abandon their founding philosophy, Torkelson and Gama have continually refined the application of those core ideas.

To get students college ready, IDEA began “AP for all” in 2014. The results the first year were not good, Torkelson said. Rather than scrap the program, dismissing it as “a reach too far,” he said, IDEA revisited the teacher training for AP instruction and “we beefed up support.”

When a school doesn’t perform up to standard, as happened at IDEA Eastside Academy in San Antonio, intervention is swift. With test scores, morale and attendance at the K-5 academy lagging at the midyear point, network administrators moved to make the campus’s 6-12 grade principal Janie Gomez one of IDEA’s first executive principals, overseeing a full K-12 pipeline on the shared campus. Gomez has data plastered around the school, and administrators monitor progress daily.

Torkelson made a surprise visit to IDEA Eastside in March to see how the turnaround process was going. Gomez was confident that the academy was on track to earn a “B” on the state accountability report, which will depend on test scores from this spring. The grades will debut for the first time in August. A “B” would be a marked improvement from the “D” IDEA Eastside would have received last year had the state been converting campus scores into letter grades as they are now. Data charts hanging in public spaces around the school showed that academic progress was trending for that “D” until Gomez took charge.

College for All

Criticized as impractical and even paternalistic, the college-for-all movement has gotten pushback from those in favor of career preparation. Critics say that college prep charters impose middle-class values on low-income students and belittle working-class families. Torkelson and Gama argue that low expectations are far more problematic.

“Kids will do the work you put in front of them. Unfortunately, if you’re a low-income child in America, the work that’s put in front of you is minimal,” Torkelson said. Kids from low-income homes and children of color are often given less challenging work than their white middle-class peers, he explained. Research backs his claim.

College should be an option for every student, Gama said, because it is still the pathway to the most secure and empowered future.

To help their students get into college, the network had to find a workable, replicable model for low-income families. Data show that no matter how much SAT/ACT prep a general education, high-poverty school does, it won’t see the kind of scores that higher-income students achieve through expensive private test prep.

However, AP courses and the tests that follow have allowed IDEA students to reap the benefits of increased rigor in school. Their coursework translates directly to their college applications. College for all has become AP for all. The network uses the entire AP curriculum created by the College Board, and it gives the tests as early as eighth grade to begin internally monitoring student progress.

Though the network boasts of its 100 percent college acceptance rates, only 50 percent currently graduate from college, Torkelson said at the San Antonio fundraiser. That’s a high number compared with their socioeconomic peers. Roughly 11 percent of students from the lowest-income quartile nationally graduate from college in six years, according to the Pell Institute.

But 50 percent is not high enough, he argues.

Some students cannot attend college right out of high school, and others have to leave college for family and financial reasons. For those students, IDEA created IDEA U, an accredited extension of College for America through Southern New Hampshire University. In these storefront, café atmospheres, students can pursue college credits with access to technology they might not have at home and the support of a tutor/counselor. Some will earn their degree through IDEA U or eventually transfer to a four-year university.

The network also has its own counselors on the campus of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, a commuter college where many IDEA students enroll. Torkelson sits on the board, and the two college counselors IDEA maintains on campus keep its graduates on track to getting their diplomas.

No excuses

“No excuses” became the hallmark catchphrase of high-performing charters in the early 2000s, with networks like KIPP and Uncommon Schools embracing stringent discipline policies and a culture of high expectations very much in line with Bush-era rhetoric. The Department of Education under President Obama favored restorative justice and positive behavior interventions, and many of the “no excuses” charters faced increased public scrutiny, leading some to downplay the mantra or abandon it.

IDEA’s understanding of the “no excuses” philosophy was always somewhat different from other networks, Gama said, and it’s nothing she plans to scuttle. In fact, it’s still embroidered on the school uniforms. When IDEA says “no excuses,” she explained, she is referring to the adults — teachers and administrators — who are tempted to let students’ poverty dictate the limits of their achievement, rather than going above and beyond to help them graduate and attend college.

“It’s an adult core value, an adult behavior,” Gama said. “We will do whatever it takes.”

At IDEA, that means bringing in Communities in Schools. The case management nonprofit helps IDEA address the social and emotional needs of students, which can otherwise derail their success.

The demands of educating students living in poverty were not a surprise to Torkelson and Gama. The two met in 1997 as Teach for America corps members working with fourth-graders in Donna ISD. They quickly saw the need for a more rigorous, college-focused culture. Students were capable, Gama said; they just needed the opportunity. The district let them start an afterschool program that grew to what Gama characterizes as “a school within a school.”

After their TFA stint was up, Torkelson and Gama went their separate ways to gather the support and know-how they needed to come back together and start a school.

In 2000, IDEA was authorized by the Texas Education Agency and began as a school to serve the colonias in Donna — small unincorporated areas where impoverished, Mexican-American families live without plumbing or paved roads. The pair walked door to door in the colonias, recruiting students — a tradition that continues to this day, Gama said.

Their signature recruitment strategy in the colonias leads Gama to scoff at the often-heard accusation that charter schools get better results than their district counterparts because they “skim” the brightest and most motivated kids. When IDEA moved into mixed-income suburbs in the Austin area, it placed its campuses in the lower-income neighborhoods, according to the network’s 2017 application for a grant from the Department of Education’s Charter Schools Program.

Gama does admit that IDEA has expectations of student conduct that might make for a difficult adjustment, not only for students but also for their families. High expectations mean more friction, more infractions, more reasons for parents to come to school and butt heads with administration. That can be irritating for some parents, Gama acknowledged, especially if they weren’t expecting the rigor. One charter critic at the University of Texas used Texas Education Agency data to calculate that between 2007 and 2012, 11 percent of IDEA would-be graduates left the school.

“It’s important that we talk about onboarding families,” Gama said.

Torkelson isn’t pushing on anyone else’s kids what he wouldn’t want for his own kids, he explained. That’s why his three kids are in IDEA schools as well, he said: “They are thriving. They are thriving with the structure. They are thriving with the academic demands.”

Per the IDEA student handbook, the charter network also does not have to admit students with criminal records or “other disciplinary problems.”

Some parents of special education students have had mixed experiences with IDEA’s approach.

Several interviewed in April 2018 credited IDEA’s intensive literacy focus with helping their kids overcome dyslexia and ADHD. One even said that what presented as their child’s dyslexia seemed to completely disappear once they were reading at grade level.

However, in November 2018, the school psychologist at that same campus, IDEA Mays in San Antonio, was sanctioned by the state for failing to deliver required services to a student diagnosed with emotional disturbance. An IDEA spokesperson said the employee was fired after the student’s parent filed a complaint.

That parent and two others whose children had autism and emotional challenges said the school was ill-equipped to handle those types of disabilities.

“I often hear from special education parents that they want us to do more,” Torkelson said, but he points to the many who have been successful. By focusing on intensive reading, math and teamwork, he said, IDEA is preparing students for life after school, where federal protections don’t guarantee them a job or housing. He wants those students to be “independent and successful.”

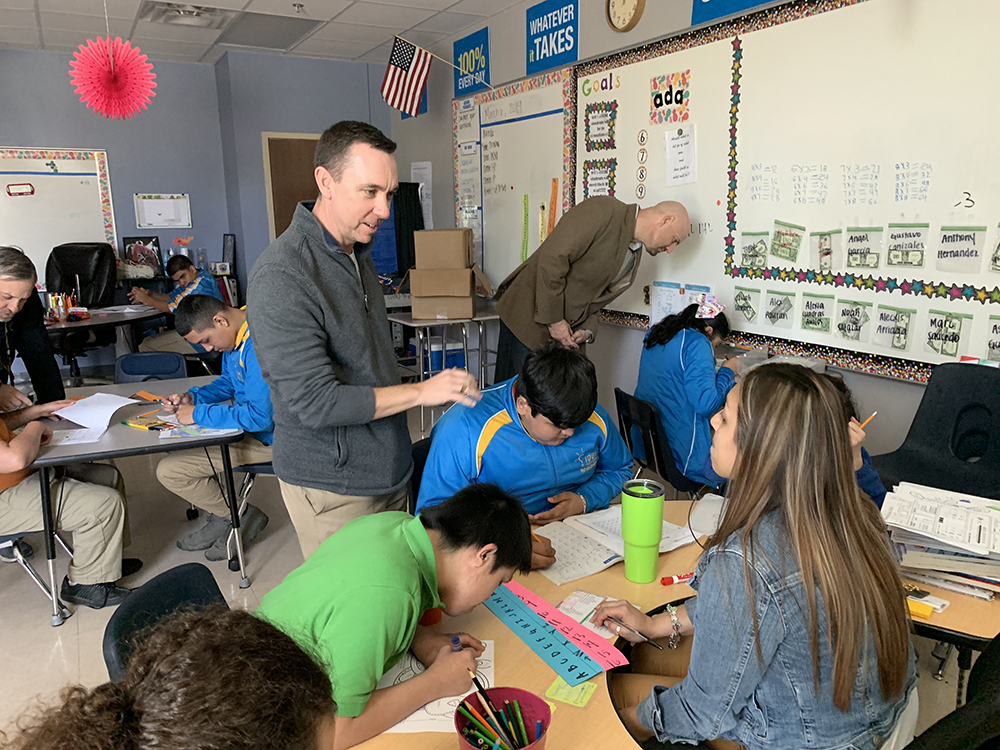

On a recent surprise visit to one of IDEA’s lowest-performing campuses, Torkelson wanted to check on general progress. He also stopped by the school’s special education classroom for students with the most individual needs. Two teachers worked with the 10 students, each moving at their own pace. Torkelson said he liked the individual instruction he saw as well as the peaceful environment. Each student was concentrating on their work, despite the visitors in the room.

Although IDEA is willing, and he believes able, to educate any student, Torkelson knows that the intensity and structure of IDEA isn’t going to appeal to every family. “I’m not looking to convince anybody of my point of view or my philosophy. I want to be a school for people who already have that point of view,” he said.

And there are plenty of them.

There seems to be no end in sight for the growth of Texas’s largest charter network, which could well be on track to surpass KIPP, which educates more than 100,000 students in 224 schools, as the largest national network. Expansion into choice-friendly Florida initially came through the 2018 Schools of Hope initiative, which brought charter operators in to start schools within five miles of “persistently low-performing” Florida public schools.

To operate Schools of Hope, the networks had to have proven success with children in the same demographics as the area where they would be planted in Florida. The program was the first state authorization mechanism for charters in Florida, where charters are typically authorized by school boards. IDEA plans to open four schools in Tampa Bay in 2021, once the leaders and initial staff have been trained.

As it grows, both co-founders acknowledge that certain campuses will have missteps and some will perform better than others. None of that, they say, gives them pause on the quality of the IDEA model. They have too many college acceptance letters to prove it.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provide financial support to IDEA and to The 74.

Lead image: IDEA Public Schools

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter