As Big ESSA Deadline Arrives, Many States Move Away From Summative Ratings for School Performance

Clear ratings are everywhere.

To plan a single evening, you could use a city’s food safety grades to pick a restaurant and Rotten Tomatoes’ “percentage fresh” ratings to choose a movie, before relying on the collective reviews of Yelp’s five-star rating system to select a bar to visit after the movie wraps.

In many states, though, it’s much tougher to figure out a clear rating for schools.

About half of the states scheduled to submit their state plans for implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act this week will use some sort of clear, summative rating for schools, like A–F grades or one-to-five stars. That’s a significant drop from the proportion of states using summative ratings in the first round of plans submitted earlier this year.

The ratings are based on students’ growth and proficiency on standardized tests, high school graduation rates, and other measures that states can choose, like college and career readiness or chronic absenteeism. The law requires states to intervene in the bottom 5 percent of schools, high schools where fewer than two-thirds of students graduate and schools where subgroups of students aren’t performing as well as their peers.

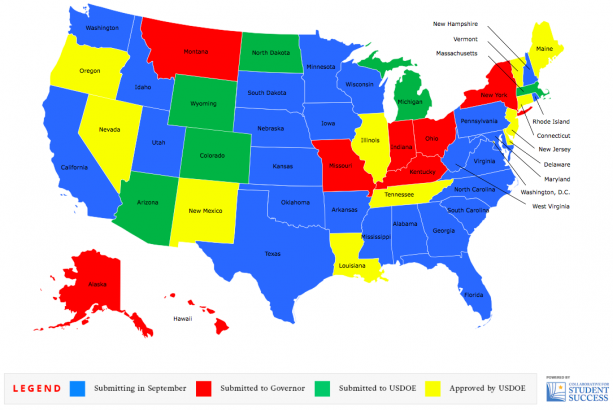

Fifteen states and the District of Columbia submitted their plans to meet the first deadline in April, and 14 have been approved. The remaining states must hit the Sept. 18 deadline, though Texas and Alabama have been granted extensions after recent hurricanes.

Clear, summative ratings offer “full transparency” and “send a clear message to parents that’s understandable on sight,” said Claire Voorhees, national policy director with the Foundation for Excellence in Education. The education reform group, started by former Florida governor Jeb Bush, advocates for the use of A–F school ratings; his state was the first to adopt it, in 1999.

Though there are plenty of possible pitfalls, summative ratings can easily do for parents what parents would have done otherwise when picking schools for their children: decide which measures of school quality matter, and at what weight relative to the others, said Jon Valant, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who blogged about summative ratings under ESSA.

Researchers with the Fordham Institute, which rated the first-round ESSA plans in three areas, including clarity of ratings, argue that “there’s simply no excuse for states to assign labels that are impossible to parse, which strikes us as an Orwellian approach to keep interested parties in the dark about school quality.”

It may help schools, too: Research on schools in Florida and New York City has also shown that test scores improve after a school gets a failing grade.

A review by The 74 of the latest version of state plans available online last week — not all of which were the final versions that will be submitted for approval by the Education Department — found 15 states are using A–F, five-star, or 100-point ratings. Another four are using text labels.

States that are using A–F ratings and the like are clear that they’re doing so; deducing how states that aren’t using them will communicate school performance is difficult, even for this education reporter.

New Hampshire, for instance, will rate schools 1–4. It might be easy to assume a 1 is the top 25 percent of schools, 2 is the second quartile, etc., but that’s not the case.

Schools with a 1 label are those not in need of state intervention; 2 means a school has consistent underperforming subgroups; 3 means it has low-performing subgroups; and 4 means it’s in need of comprehensive support.

“This type of reporting system privileges the robust information provided by the full dashboard of school indicators, while minimizing the role of an overall summative determination beyond its clear and necessary use for identifying schools in need of targeted or comprehensive support,” the state’s plan says.

Contrast that to Indiana, which uses an A–F system. All school indicators are fed into a system that adds up to 100 points. An A school is 90 or above, B schools are 80–89.9, and so on, with F schools getting fewer than 60 points. F-rated schools will be identified for comprehensive support and must get to a C rating before they can leave that status.

That’s in sharp contrast to the first round of ESSA states, in which 14 of 16 states used some sort of summative rating. Three states used A–F scales, three used 100-point scales, and two used five-star systems. Another three used text labels and three used tiered systems.

There are plenty of critics of using summative ratings, arguing it’s a reductive way to judge school quality, and a data dashboard or report card, like some states are using in their ESSA plans, is a better way to judge schools.

California has perhaps attracted the most attention for its use of a dashboard rather than a clear summative rating. Critics in particular pointed to its use of outdated data, lack of optimization for the mobile devices where many low-income parents would see it, and zero translation options beyond Google Translate. The state Board of Education and governor approved it and sent it out for federal approval last week.

(The 74: Opinion: New California Accountability Dashboard Provides Little Light for Poor Families)

The summative-rating-versus-dashboard issue shouldn’t be an either-or decision, but an and-both, Voorhees said.

“You would never want just an A–F label, separate and apart from that diverse dashboard,” she said.

The underlying law doesn’t require states to use summative ratings, though the Obama administration called for them in now-overturned accountability regulations.

“The good news in general is that given that it’s not required under ESSA, by any means, there are a good number of states that are sticking to the summative rating,” Voorhees said.

If the first round is any guide, though, it likely won’t matter if states don’t have an A–F, five-star, 100-point, or other summative rating. The Education Department has so far approved more than a dozen state plans — including at least two that don’t include summative ratings.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)