Obama Administration, At Odds with Congress, Doubles Down on ESSA Equity Regulations

Washington, D.C.

Obama administration officials last week released school accountability regulations that they say protect educational opportunities for poor and minority children while balancing the need for flexibility for states and schools — even as those proposals again put them at odds with Republicans in Congress.

“We must be committed to providing all students — regardless of their race, religion, country of origin, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or family income — with a high-quality education. That is a civil right, and all means all,” Education Secretary John King said at a May 26 roundtable discussion at an elementary school in southeast Washington.

King brought along a high-ranking White House policy director and two civil rights heavyweights to underscore his point.

King’s department released new school accountability, data reporting and state planning proposals that same day, almost immediately drawing congressional rebuke. The accountability regulations came on the heels of a funding proposal that also put federal education officials in conflict with the GOP.

King was careful to emphasize, perhaps a dozen times over the course of the event, that the regulations “are the product of lots of listening” to stakeholder groups around the country, and that they’re an effort to balance flexibility for states with necessary civil rights protections.

Cecilia Munoz, director of the White House Domestic Policy Council, also joined King at the event. President Obama and his administration are committed to doing everything they can to watch out for children, particularly those who start life with the least, Munoz said.

Munoz and King spoke at J.C. Nalle Elementary in the Marshall Heights neighborhood of southeast Washington. The selection of Nalle, D.C.’s first community school, was no accident. The neighborhood has a history of trouble: in 2005, a woman was found shot to death on the school’s playground. And the students there are some of those most likely to be left behind without strong civil rights and accountability education laws: 93 percent are black, 7 percent are Hispanic, and 99 percent are eligible for free and reduced-priced lunch, a common measure of poverty.

But by 2013, the students at Nalle had posted the biggest gains in test scores among D.C. Public Schools after longer days, Saturday classes for students and parents, and new math and reading curriculum were put in place.

Munoz and King held a roundtable with teachers and advocates representing the civil rights community. Like the selection of Nalle, the presence of Wade Henderson of the Leadership Council on Civil and Human Rights and Janet Murguia of the National Council of La Raza sent an intentional message.

Murguia said her group expects a “strong and robust and rigorous federal role” in school accountability, as a civil rights protection.

And Henderson, like King did two weeks earlier, linked the need for strong federal accountability to school segregation. Tough federal protections are necessary when “many schools are still struggling to achieve the promise of Brown,” he said, referencing the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision.

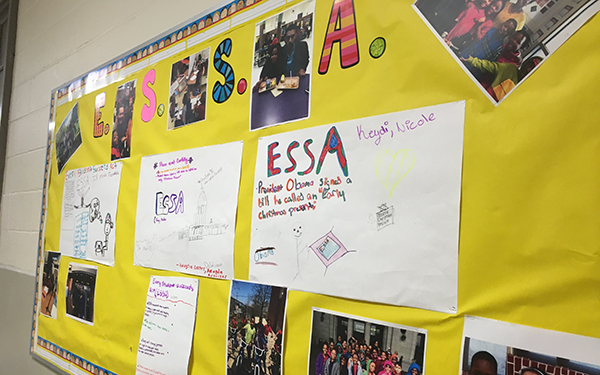

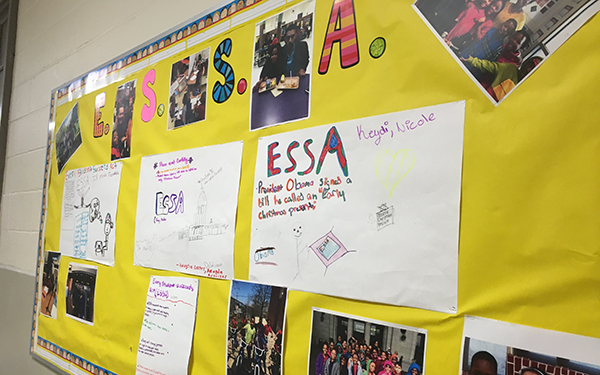

Student projects explaining the Every Student Succeeds Act hang on a billboard at J.C. Nalle Elementary in southeast Washington, D.C. Education Secretary John King held an event at the school May 26 to tout new school accountability regulations. (Photo by Carolyn Phenicie)

The accountability proposal the Education Department released last week would require states to score schools on academic achievement (progress on tests for elementary and middle schools and graduation rates for high schools) and progress toward English language proficiency. They’d also have to measures indicators of school quality or student success, like student and educator engagement, postsecondary readiness or completion of advanced coursework.

States and schools would have to provide targeted supports to schools where specific subgroups of children — as judged by race, disability, English language learner status and other challenges — aren’t making appropriate progress. They would have to give comprehensive support to the bottom 5 percent of schools in the state, high schools where fewer than two-thirds of students graduate on time, and high-poverty schools where subgroups of students fail to make progress after targeted interventions.

The law requires states to put a “much greater” weight on the measures of academic achievement. The department’s regulations don’t propose a specific numerical weight for academic achievement, but schools identified for comprehensive support can’t be removed from that status by improving non-academic factors alone.

The proposal will be open for public comment from May 31 to August 1. The Education Department might or might not consider those public comments before it releases a final version later this year.

The Congressional Claws Are Out

Republicans in Congress immediately pounced, saying the regulations merit close review to ensure the proposal comports with the law.

House Education Committee Chairman John Kline said he is “deeply concerned the department is trying to take us back to the days when Washington dictated national education policy.”

Sen. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the education committee, said if the regulations don’t implement the law the way Congress wrote it, he will introduce a resolution under the Congressional Review Act to overturn it. That law allows Congress to overturn federal agency regulations — but requires the president to sign off to block the agency action. Given the public support from the White House for the regulation, it’s very unlikely Obama would sign such a resolution. The regulation must be passed within 60 days of the rule being finalized, so GOP leaders likely can’t just wait for a Republican to possibly move into the White House.

Kline, meanwhile, vowed to use “every available tool to ensure this bipartisan law is implemented as Congress intended.” (Other options could be encouraging an affected state or district to file a lawsuit, or including a provision in the department’s annual $70 billion funding bill banning it from using any money to implement the regulation.)

King and Munoz were undeterred — again, repeatedly emphasizing that they’ll listen to public comment, and that the regulation proposal appropriately balances state and local flexibility with civil rights protections.

“The regulations reflect the statute, the input that we received and the longstanding commitment that the president and administration have had to excellence and equity for all students. I think that’s what’s reflected in the regulations,” King told reporters after the public roundtable.

Munoz rejected the idea that the carefully curated coalition that came together to pass the law that replaced the widely disliked No Child Left Behind would disband over efforts to regulate it.

“I’m quite confident that that coalition is not going to break up,” she said. “The details matter a lot, but the consensus around the need to accomplish what we in fact accomplished by passing the law, and what we believe we will accomplish with these regulations, is quite strong.”

And even as congressional Republicans criticize the regulatory proposal, their Democratic colleagues have emphasized the need for strong accountability provisions, King noted.

“[Rep. Bobby Scott, the top Democrat on the House Education committee] has often made the point throughout the work on ESSA that the law can’t just be about identification, it has to be about meaningful action to ensure better outcomes,” King said.

“We do think it’s important as states build these systems that when schools are identified [as falling behind] that they put in place interventions that make a real difference and improve outcomes, and that they continue to provide support to ensure that the outcomes get better,” he said.

The tough accountability provisions are essential to the president’s goals for the law, Munoz said: “At the end of the day, the goal here is to make sure that we’re closing the gap wherever there is a gap.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)