As a Racial Reckoning Sweeps the Nation, Parents Still Await a ‘Rallying Cry’ to Change How Race and History Are Taught in Schools

By Zoë Kirsch | June 23, 2020

When Natasha Capers, a Brooklyn-based mother of two, found herself sitting in the National Constitution Center with her son and his classmates on a field trip to Philadelphia in 2017, she was shocked to find that, despite the room being filled with mostly Black and Latino students, his fifth-grade teacher was skipping over one important detail.

The Constitution hadn’t given rights to the people who looked like them.

“Are we not going to talk about the fact that the Constitution did not give any of us in this room anything?” she wondered. Capers is the director of the New York City Coalition for Educational Justice, an advocacy group that has, for three years, pushed the city’s school system toward the thing that she sought in that moment: a “culturally responsive” education — teaching that centers the student experience, so learners can see themselves in instruction and how it’s delivered.

“Culturally responsive education is acknowledging that yes, when the Constitution was ratified, it actually did not free us,” Capers says. “We can’t ignore the elephant in the room.”

Experts have pointed out that the national dearth of culturally responsive education is one of the reasons this country still hasn’t confronted its history of race-based oppression. And while the U.S. has seen a recent reckoning prompted by protests over the death of George Floyd at the hands of police — in the form of the removal of cops from schools, declarations of Juneteenth as an official holiday, and the like — implementing the instruction needed to contextualize those events for students has proven a more difficult task. Scholars say that, barring a surge in public will, the path forward is a long, uphill battle. In New York City and other communities around the country, that fight has only just begun.

In Oklahoma, for instance, it wasn’t until February of this year that the state decided to include the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in its statewide school curriculum, recognizing after decades of widespread cover-up that students should learn about the heinous event.

https://twitter.com/NurseKathie/status/1233430228623556609

Some smaller districts have made progress. In San Francisco, leaders voted five years ago to expand an ethnic studies program addressing structural racism, identity and social justice to 19 high schools. The Board of Education recently reaffirmed that decision, in light of contentious efforts at the state level to expand similar curricula to all students. The state of Washington has created a rubric for measuring bias in classroom materials so that district administrators can critique their own programs.

Still, most states and districts haven’t taken such steps, due to the political controversy generated by the idea that the courses teach divisiveness and are somehow anti-American.

“[Nationally] there hasn’t been a rallying cry,” says Capers.

Gloria Ladson-Billings, a teacher educator based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says there is still widespread misunderstanding among instructors about culturally responsive pedagogy — and about its cousin, “culturally relevant” learning, a term she coined in the 1990s.

“We as a country are challenged,” she says. “Most people don’t understand what it is they’re implementing.”

According to Ladson-Billings, culturally relevant pedagogy has three components: recognizing that students learn more than teachers can test, acknowledging that every child has their own culture and the right to access another one at school, and critical consciousness, also known as the “so what” factor — the reason the instruction has value.

She says that last piece can inspire teachers to connect their lessons to recent events.

“You’re upset about police brutality?” she says. “Take that pen and paper and write me an editorial I can send The New York Times.” Alternatively, in math: “You’re upset about what’s happening out there? I want you to do a survey. Come up with a representative sample of the 11th and 12th grade and build me a survey about how students at this school are feeling about the protests.”

Research shows that culturally responsive learning unlocks numerous benefits for students of color and white students alike. It can decrease dropout rates and suspensions and boost student self-image, attendance, participation, GPAs and graduation rates.

In San Francisco, for example, the average freshman who took an ethnic studies class improved their GPA by 1.4 grade points and attendance by 21 percent. In Tucson, Arizona, students who enrolled in Mexican-American studies courses performed better in math, reading and writing — and were more likely to graduate.

In 2006, Arizona state Superintendent Tom Horne took issue with the Tucson program after a Latina labor activist told students that “Republicans hate Latinos.” He urged lawmakers to pass legislation banning the program, and in 2010, they did. Seven years later, a federal judge ruled that law racist and unconstitutional. The district was eventually able to re-implement its program under a different name, according to local administrators.

‘New York City isn’t there yet’

New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has long been a proponent of culturally responsive learning, saying, “The idea of having culturally responsive and sustaining curricula and pedagogy is not a matter of just educational practice. In many of our communities, it’s a matter of life and death.”

In July 2019, the district responded to the state Education Department’s recently released “Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework” by adopting its own definition of the term. The following fall, Carranza announced that he was inviting a group of teacher “fellows” to develop a complementary list of best practices. He also said the district would rewrite the NYC Reads 365 book list to be more inclusive.

Capers and her colleagues at the New York City Coalition for Educational Justice cheered the changes but had hoped for more. Along with researchers at New York University, they had found that, while 85 percent of the city’s public school students were Black, Latino or Asian, 84 percent of books in 10 widely used K-through-fifth-grade curricula were written by white authors, and 51 percent had white main characters. In a follow-up study examining books read in early childhood and middle grades, they discovered a dramatic overrepresentation of white authors and characters, especially in 3-K and pre-K programs.

District officials say the teaching fellows met from Nov. 5 through March 10, when the pandemic cut sessions short, although they declined to tell The 74 where the list of best practices could be found.

Overall, the district has spent $23 million running implicit bias training for tens of thousands of staff — work that’s been met with some resistance, especially in parts of Staten Island and Manhattan, according to Christopher Emdin, a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, and the author of For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood.

Emdin says that every district should supplement professional development with updates to the benchmarks it uses to evaluate teachers, and with a careful review of its curricula. Each district should have at least one person overseeing that process, he adds.

“You can’t have an educator understanding the need for culture when all the tools at their disposal are acultural,” he says. “We have an entire infrastructure that has to shift … New York City isn’t there yet.”

The chancellor has encouraged schools to use materials like the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project from The New York Times, which re-examines the legacy of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans, and “Hidden Voices,” a social studies project celebrating figures overlooked by traditional history. According to the department, 80 percent of K-8 students districtwide are using the Passport to Social Studies curriculum, which includes lesson plans about African, Latino, Asian, Middle Eastern and Native people. District leaders have said that, when they do solicit a new core curriculum, vendors will have to comply with the city’s definition of culturally responsive learning.

“This work is more important now than ever before, and we remain steadfast in our commitment — because research shows it makes a difference in children’s lives,” DOE spokesperson Danielle Filson told The 74.

But advocates have noted that the department didn’t specify a timeline for the curriculum solicitation process, nor did it earmark funds for it.

On June 10, activist and Washington Heights-based math teacher José Vilson drafted a petition addressed to state and city leaders detailing 17 demands, including that the DOE invest more funding in culturally responsive learning, implement anti-racist curricula year-round, and offer culturally responsive homeroom or advisory period in every school. Three days later, the letter had racked up more than 1,000 signatures from NYC teachers, students and community members.

“With these demands, we can actually see a way forward for our Black students and communities who deserve a more robust, anti-racist, human-centered school system,” Vilson writes. “We can no longer settle for simple reforms that do not heal the root of our school system’s racial disparities.”

‘Why is it that I only learn about Black history in February?’

Tanji Reed Marshall of The Education Trust encourages each district leader to put their money where their mouth is. “Acknowledgement is fine, but it takes funding to do the work,” she explains. Marshall leads an equity team that analyzes and improves student assignments from partner schools in communities large and small; urban, suburban and rural. “I can talk about what I acknowledge every day and twice on Sunday and feel really good about it,” she says. “But come Monday, if all I did was talk about it, I’m back where I started.”

Marshall expressed concern that, after the pandemic struck, one of the first cuts Mayor Bill de Blasio made to the city budget was a $49 million reduction to the “Equity and Excellence” initiatives intended to tackle disparities among students.

“If you’re saying all of this but taking away money from the thing you say is important to you, it’s not important enough to you,” she says. “Where we put our money tells you our values. Period.”

In February, Marshall visited New York City to interview students in focus groups as part of the district’s efforts to reimagine high school. She was disappointed to learn that the teenagers she spoke with didn’t see themselves reflected in their high school curricula.

“I can’t tell you how many asked, ‘Why am I only learning about the Holocaust? I’ve been learning about it since the third grade. When can we learn about other people? Why is it that I only learn about Black history in February?'”

Emdin, of Teachers College, explains that students can grow disillusioned when the issues they’re told to study don’t tie into their life experiences. “If the tools we’re asking young folks to read don’t signal them, it highlights a certain hypocrisy,” he says. “It doesn’t feel authentic.”

Marshall’s team follows an iterative process when working with partners. They evaluate each curriculum on several fronts, weighing how it aligns with student ability — asking whether administrators and teachers are projecting assumptions about skill level onto students based upon factors like race — and examining whether learners are presented with real-world problems that leverage their daily experiences.

Marshall elaborates: “Do you get the sense that students will be able to lean on who they are as individuals, and as members of their community, as they work through assignments?”

Finally, the team addresses the issue of representation, which, as Marshall points out, isn’t just about counting the appearances of non-white people, but is rather about exploring how those individuals are portrayed.

Ladson-Billings explains this by way of a sobering example — a French teacher she once met who wanted to know why African-American students were enrolling in her class and dropping it after only a few weeks.

Ladson-Billings asked the teacher about her classroom environment. What did the French room look like? Was there anything on the walls?

The woman said that yes, there was — she had taped up travel posters of the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe.

Were there any images in the room featuring Black people? Ladson-Billings wanted to know.

Again, a nod. Alongside the Parisian architectural feats, the teacher had displayed posters from Francophone Africa, showing people with bare chests.

“How do you think kids are feeling?” Ladson-Billings says. “The white kids in here get connected to Paris, and I get connected to people who are not really dressed.” She told the teacher to replace the old posters with pictures of Black French-speakers in Louisiana or Haiti.

“I just really want to emphasize,” she says, “that whenever you want to do something big, you have to do it in small steps. The idea that we’re telling teachers, ‘I want you to be culturally relevant,’ is going nowhere. You have to give people an opportunity to try a little bit. Success breeds success.”

‘It’s not enough to say BLACK LIVES MATTER’

S.T.A.R. Academy is a small school on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where students learn from pre-K through the fifth grade. Assistant Principal Jodi Friedman has been there for 16 years, watching the institution emerge from its struggles — it was once given an “F” rating by the city — to become a beacon of culturally responsive learning studied by Carranza.

“Many of us, as teachers, had to relearn history. We were teaching based on standards from the city and state. Those are often incomplete or incorrect and missing important perspectives.” —Jodi Friedman, assistant principal, S.T.A.R. Academy

That change has taken hours of continuous learning and reflection, she said.

The team began by focusing on content. First, they revamped social studies classes — “it was the easiest entry point,” says Friedman — before moving on to other subjects.

Leadership invited teachers to examine their standards, and asked them to consider whose stories were being told there and whose were left out. Then, during the summer of 2016, instructors were given time to research their own curricula. Later, they convened in grade-level teams to address what they had learned and to incorporate it into new units of study.

The change was immediate. Fourth-grade history, which had previously framed explorers’ journey westward as “heroic,” now centered the experiences of Indigenous people. At the end of the unit, students were asked to write about whether or not the school should celebrate Columbus Day.

“Many of us, as teachers, had to relearn history,” says Friedman. “We were teaching based on standards from the city and state. Those are often incomplete or incorrect and missing important perspectives.”

Recently, in light of the protests, the school’s kindergartners watched a video called “Safe” and discussed the things that make them feel most secure. Fifth-graders were encouraged to express themselves artistically. One student wanted to share a drawing that she had made on the school’s Twitter account. Some wrote articles. Others just wanted to talk.

Ladson-Billings says that culturally relevant pedagogy will be all the more important next school year, when students return to classrooms after a pandemic leveled disproportionate harm against communities of color.

“In New York City, kids not only have been home for [months], but they’ve also seen death and dying all around them,” she says. “You can’t pretend that didn’t happen. Before you can do anything about the academic part, you have to attend to how kids are feeling.”

For those worried that adopting a culturally relevant framework isn’t possible in light of budget cuts, Ladson-Billings invites administrators to think creatively about reallocating their resources to center Black and brown students, and to consider the ways that the virus has shown leaders the feasibility of goals they had previously deemed unachievable.

“Before COVID-19, if you had said, ‘Give all the kids a computing device,’ all you heard was ‘You can’t do that.’ Before COVID-19, we thought you had to test kids every year. If there’s any opportunity here, it’s that we could do a hard reset and start to think very differently.”

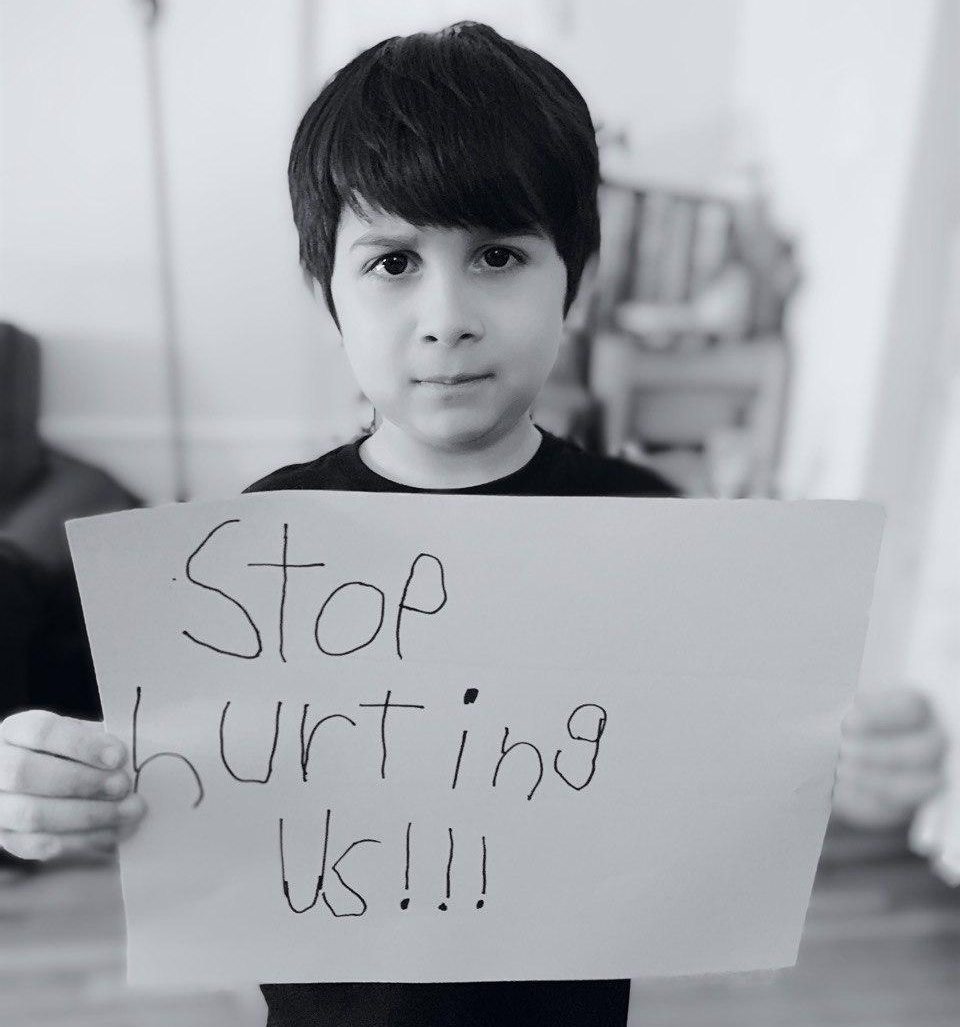

Lead image: Demonstrators marching to a rally at the U.S. Department of Education on June 19 carrying signs saying “My students will not be hashtags” and “Teach the Truth.” (Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter