Are Schools Ready for Competitive Video Gaming? By Including Girls and Downplaying First-Person Shooters, Cleveland Teacher Hopes to Chart New Course for ‘Esports’

Updated Jan. 8

If a new effort takes hold, competitive video gaming could someday be much more popular in U.S. middle and high schools, perhaps as commonplace as basketball, marching band and the big spring musical.

Led in part by a former U.S. Education Department official who is now in the classroom, the undertaking could also expand both the size and diversity of the “esports” player and spectator base — a group that, in the United States at least, remains mostly white, male and upper-middle-class.

The total esports audience is expected to grow 15 percent this year, to 454 million people watching others play fast-moving player-versus-player matches onscreen — sometimes in loud amphitheaters, but often remotely through digital streaming services like Twitch.

The estimated 2019 revenue of esports is expected to top $1.2 billion worldwide, six times as big as in 2014.

Quite simply, esports are having a moment: NBC recently said it plans to air “The Squad,” a new comedy series about a group of friends who bond over competitive esports. And CBS earlier last month said it was producing a sitcom pilot of its own, about a retired pro basketball star “who attempts to reconnect with his estranged son by buying an eSports franchise.” Corporate sponsors are taking note — one league this year inked sponsorship deals with several top brands, including Coca-Cola, Toyota, T-Mobile, HP and Intel.

Academia is also taking note: This Thursday in Washington, D.C., the Education Department is holding an “Ed Games Expo,” complete with a conference on esports at the Wilson Center. Perhaps more significantly, colleges and universities are fielding esports teams and offering millions of dollars in scholarships to high-school-aged video gamers.

Actually, that was one of the key reasons to start a new league, said J Collins, a computer science and game design teacher at Hathaway Brown, a private girls’ school in Cleveland. Collins, who is a nonbinary gender and prefers the pronoun “they,” previously led game-based education and ed-tech policy initiatives at the U.S. Department of Education.

“Right now, those scholarships and that money are primarily going to young, white, affluent boys,” Collins said. “There’s nothing wrong with that, but it needs to be highlighted that that is not the only model that we can have for K-12 esports.”

That realization grew partly from Collins’s own transformation. Collins, who grew up male, recognizes “how much the game industry markets to and relies on ideas of boyhood and masculinity.” The teacher recognized a hole in the educational market for nontraditional gamers.

“As a transgender teacher and as someone who works at an all-girls’ school, I feel like I have to respond to that. I can’t just bring in another esports program designed for boys that mostly plays games targeted at boys. It won’t work. And it won’t create the kind of inclusive program that all students need in order to thrive.”

Mischief League

At Hathaway Brown, Collins helped launch the first U.S. all-girls varsity esports program last year, serving as its coach. Recent statistics show that although females comprise 46 percent of gamers overall, the vast majority of competitive esports players are male.

Collins has said the trajectory for girls in esports is likely the same as in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, in that they’re often as high-performing as boys but don’t pursue it because they have few role models — and even fewer positive experiences.

Collins and others hope the co-ed Mischief League will be different. For one thing, it’ll be free and available not just to schools but also to libraries and other community institutions. For another, the games will look a lot different. Most popular esports titles are first-person, team-based shooters, such as Call of Duty, Counter-Strike, and Overwatch, or multiplayer online battle arena games such as Dota 2.

Mischief League plans to keep only Dota 2 in its initial four-game catalog. The others — more PG-rated and likely to pass school board muster — include a cartoon fighting game called Brawlhalla, a drone racing simulator called Liftoff and the massively popular world-building game Minecraft.

Wait, competitive Minecraft?

Actually, Collins said, the Minecraft matches will be more collaborative than competitive. The plan is to post a challenge related to computational thinking that two opposing teams take up — they’re expected to pursue it as collaborators over the course of the school year. Judges will score the projects and apply the scores to the bottom line of both teams. “Ideally, these two schools or libraries will be talking to each other all year, trying to figure out the best way to score the most points,” Collins said.

That alone will set the new league apart from larger, better-funded efforts such as the High School Esports League and PlayVS.com. Those feature both sports and shooter titles that typically appeal to boys, but they exclude a large potential player base.

Collins called it the Die Hard effect: “Die Hard is a wonderful movie. It has a certain demographic that appreciates it and a certain demographic that doesn’t. And it’s totally fine to have a movie night and invite everybody over to watch Die Hard. But don’t be surprised if some people don’t show up.”

CJ Melendez, a spokesman for the High School Esports League, which counts more than 2,000 schools and 50,000 students as members, said the organization had no formal response to the new league’s formation but added that they’re “happy to see more organizations support teens and young adults taking part in esports!”

‘Can you build a team?’

One of those teens is Emma Young, 18, a senior at Hathaway Brown and one of the original team members. She said the league is giving her an opportunity to play cooperatively with teammates for the first time. “Not a lot of girls are into the games that I’m into — so to have people to play with is a new experience that I’m not too familiar with, and it is taking getting used to. But it’s also really nice.”

Young doesn’t play first-person shooters, opting for more complex strategy or role-playing games “that tell a story.”

“It’s like a movie or a book,” she said. “It’s another way to tell a story, just maybe this time it’s interactive. Just to have something that is meaningful to me in my life — and to see it get some recognition as not just something mindless and violent and just for boys — is really exciting.”

Teams in the new league will also be required to cycle players through all four games, much as Olympic decathletes would. That moves schools away from drilling players obsessively on one game. Because everyone is a kind of generalist, “It changes the core loop of what you’re doing from ‘Are you good at this game?’ to ‘Can you build a team? Can you navigate social structures and community to create a society inside of your school?’” Collins said.

Most of the competitions will take place online, but the league encourages teams — it is starting the season with seven Cleveland-area schools and one library — to meet up at least three times a year, including at a live championship. That may be logistically challenging, Collins said, but it’s worth the trouble. “When this happens in person, it is such a special thing to see students from a poor school and a rich school, an urban school and a rural school — all of these people come together, and sit down and start playing. They won’t even ask each others’ names; they’ll just sit down and start playing games together to get to know each other.”

Because it’s free to join, Collins said, the league is attracting different kinds of schools, both public and private. Last spring’s first-season finalists, both from northeast Ohio, were a rural school with a high poverty rate and an urban school where fewer than 5 percent of students met state math requirements. Based on interest from schools in other states, Collins expects the league to expand in the coming years.

Engaging students ‘where they are’

The league is run by the nonprofit GG+, whose board of directors is entirely female, made up of four women who work in gaming and educational technology. One of them, Elizabeth Newbury, directs the Serious Games Initiative at the Wilson Center, which has developed games around climate change and the federal budget. She said many teachers are looking to esports as a way to understand what their students love. “It’s really about meeting students where they are and engaging them where they are.”

But shouldn’t school be a place to challenge kids with things they don’t already like? Newbury pushed back: “I think that the point of education is really to afford those growth opportunities for students and to give students a place to belong,” she said. “That can be done through affording them opportunities they wouldn’t necessarily have at home.”

The new league will be welcomed by many gamers, but it faces a few challenges if it wants to grow and be successful long-term, said Mark Deppe, director of esports at the University of California, Irvine. “First, they’re playing games that currently don’t have big audiences, so they may struggle to get people interested,” he said via email. “The other is that they will still need to address the societal issues that hurt diversity.”

Those include a bias toward encouraging boys to play video games and online hostility toward people who don’t look, talk and act like “real gamers,” he said.

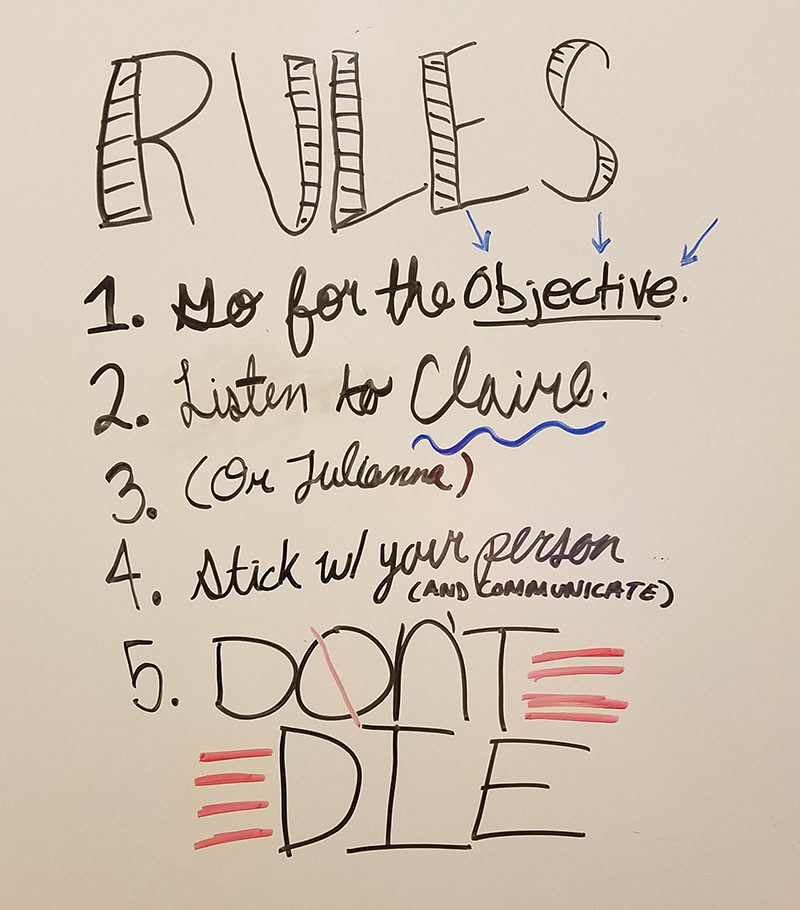

Members of the new league say they’re drawn by the same quality that has always attracted kids to afterschool activities: a sense of fun. “School is already very stressful,” said Claire Hofstra, 15, a sophomore and Hathaway Brown team member. “Video games are a good way to de-stress.”

Having to learn the intricacies of four new, often unfamiliar titles also helped the group bond. “We all struggled together,” she said. “We didn’t really care if we won or lost. We preferred to win, but we had fun either way, and that’s all that mattered.”

Disclosure: Greg Toppo, author of “The Game Believes in You,” will be participating in a panel discussion Thursday on esports at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)