Why Women Excel at Prized ‘Soft Skills’ but Still Trail Men When It Comes to Being Hired for the STEM Careers of the Future

It seems like an obvious example of supply and demand.

For years, business leaders have lamented a shortage of workers with abilities that are still beyond the reach of the smartest machine, such as improvising solutions to unanticipated problems and boosting teamwork and morale.

Women outperform men in many of the underlying skills that lead to job success — skills commonly referred to as noncognitive because, like emotional IQ, creativity, and conscientiousness, they’re not clearly predicted by test results.

The demand for soft skills, as they’re also known, was borne out in a 2017 Harvard study that found that “social skill-intensive occupations” — including teaching and some computer science and health care jobs — had increased by 12 percent since 1980 and enjoyed higher wage growth. Positions that demanded lots of brain power but little social aptitude had declined.

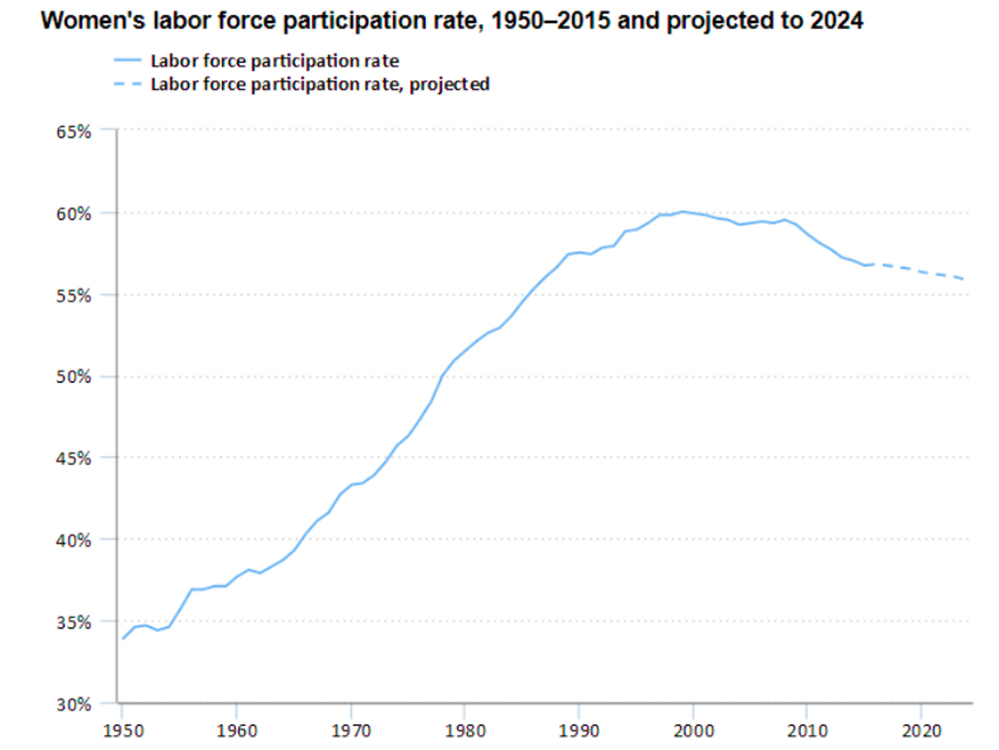

The huge rise over the past century in the number and percentage of women who work in the U.S., highlighted by more recent nationwide efforts to steer young females toward traditionally male-dominated STEM careers, would appear to give women at least an equal shot at great jobs.

But it hasn’t turned out that way — at least not yet.

The percentage of women who work has dropped three points since 1999 — driven largely by increased school enrollment rates and job competition among older teenagers, according to the Department of Labor. Even so, nearly 57 percent of women in America were part of the labor force in 2015, up from 38 percent in 1960. And women continue to increase their share of the total workforce: They are now nearly 47 percent of all workers, up from one-third in 1950.

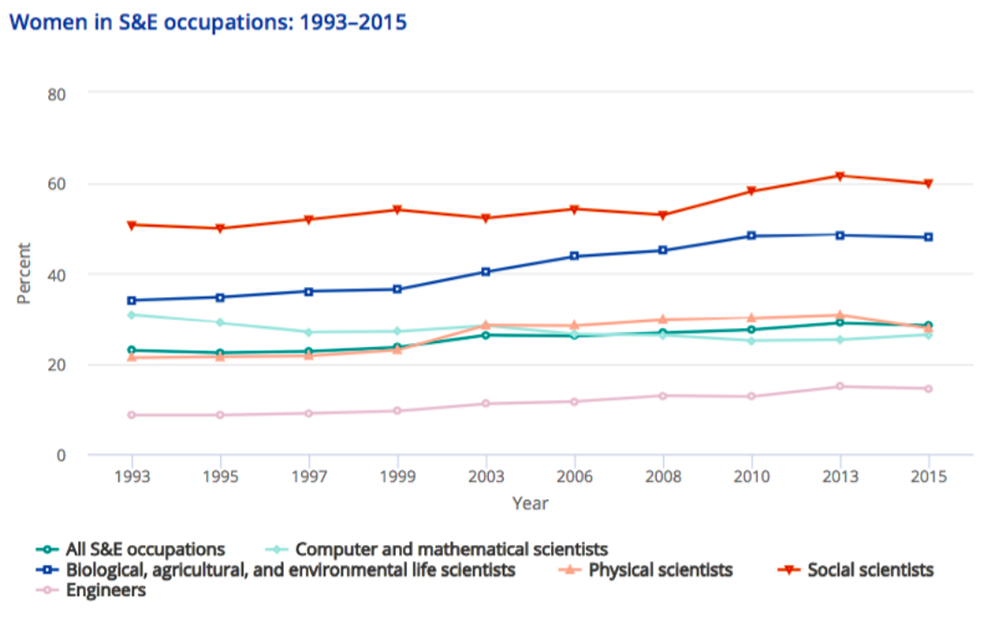

Census and survey data tell two stories. The percentage of female scientists and engineers rose to 28 percent from 23 percent over the past two decades, with substantial increases in life science fields, such as biology and medical research, and in social science (psychologists and sociologists). But only 15 percent of engineers are female, and overall gains for women in science and engineering occupations, while considerable, do not come close to reflecting the fact that women are about half of college-educated workers.

Disparities are particularly evident across racial and ethnic categories: Despite gains, black and Hispanic women make up just 6 percent of women who have science and engineering jobs.

Advocates and researchers say persistent gender stereotypes keep many women from seriously considering these positions and leave insufficient support for the few who do. Childbearing and motherhood come with opportunity and wage penalties and may divert women who are in science and engineering careers to lower-paying but more flexible middle-skills health care jobs (like lab technician or pharmacist) — a sector that is now 70 percent female.

The push for soft skills often fails to take into account these disadvantages, experts warn.

“The fact that a curriculum may be incorporating soft skills — and despite what we hear employers say about soft skills all the time — that hasn’t moved the needle,” said Lois Joy, associate research director at Jobs for the Future, a nationwide workforce organization. She said women typically lack established career pathways, including mentoring and professional networks, that often help men succeed.

“It doesn’t matter how well girls are communicating if they’re not communicating to the right people,” she said.

She and other workforce specialists point to successful programs — vocational schools that support middle school girls along “male” career pathways and nonprofits that absorb childcare costs for would-be career-switchers getting tech training. But these remain the exception.

“We still have to marry the relationship between workforce and wages with the socialization process that leads to women choosing the occupations that they do in greater numbers than men,” said Nicole Smith, chief economist at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. “Technology has resulted in the influx of women in the labor force. What we haven’t seen is women moving toward specific occupations that pay better.”

If you build it, she will come

A San Francisco tech worker and social media activist decided to help local women do just that.

Michelle Glauser likes to say that when she completed an expensive software engineering program and entered the tech field — including a job at the cloud communications firm Twilio — her income tripled. But she also found herself part of a profession with little gender or ethnic diversity and costly barriers to entry for “non-stereotypical engineers.”

She wondered if the problem was getting worse. By driving San Francisco property values sharply upward — the median cost of a house rose from $666,000 in 2012 to $1.57 million in 2018 — the tech industry displaced the very people, particularly low-income women, who would particularly benefit from the kind of training she had received at Hackbright Academy, which calls itself “the leading engineering school for women in the Bay Area.”

Partnering with local tech companies that were looking to build diversity, in 2016 Glauser launched Techtonica, offering a six-month training program in web development to 10 women of color earning less than $50,000 a year. Along with web development, the initiative sought to build the women’s workplace skills, such as project management and data analysis.

The small initiative offered advantages that most STEM programs can’t match. Business partners helped lead and picked up the cost of the training, as well as housing and childcare expenses (and laptops). Partners mentored individual apprentices, and the course culminated in job offers for each woman. In effect, the program functioned as a job network the women didn’t have.

Glauser plans to expand Techtonica beyond the Bay Area. For now, it remains a sought-after boutique offering: The organization received 170 applicants for its second 10-person cohort in 2018. Glauser suggested there would be similar interest elsewhere if local business supported such efforts.

“I’ve done a bunch of research — every single city that has a high number of tech jobs has high income disparities” across its population, she said.

Persisting stereotypes

Females get better grades at every educational level in every subject and have higher college graduation rates: They earn 57 percent of bachelor’s degrees, including 50 percent in science and engineering subjects, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Female labor has provided a huge boost to the nation’s economy, but a dam-burst of highly qualified women into science and technology has only partly materialized.

Why doesn’t superior academic performance, drawing on non-cognitive prowess, translate into even greater STEM employment gains for women?

Experts cite the fact that women remain primary caregivers for children, which impedes their careers in many ways. A mother earns 20 percent less than a father in the years following the birth of their child, according to a 2018 study that found that the gender pay gap could be largely explained as a penalty for having children. Time away from work, reduced work hours, and decreased pay all contribute.

The economists also found that women move to jobs at “family friendly” companies offering flexible hours and family leave days after having children. Before the birth of a child, for instance, men and women are equally likely to work in the public sector; 10 years later, women are 10 percentage points more likely to have these jobs.

The lead researcher, Henrik Kleven of Princeton, told Vox that some of the effects were subtle, such as a mother not being offered assignments with longer hours or travel “because of the perception that they are the primary caregiver to a child.”

Those cultural cues continue to shape not only whether jobs are seen as innately male or female, but also what men and women value in their jobs: Men put a greater premium on higher earnings, while women value stability and flexibility.

“The socialization process leads women into intellectual and caring professions in greater proportions than men,” said Georgetown’s Smith. “It leads women to believe this is where they belong. They have a longing to care, to give, to nurture that overrides a concern about wages.”

Even the behavior correlated with professional success differs by gender. A 2006 study found that “agreeableness had the greatest influence on gender differences in earnings: men were considerably more antagonistic (non-agreeable) than women, on average, and men alone were rewarded for that trait.”

Another researcher summarized data last year showing that “very agreeable” men — in the top quintile of agreeableness — earned $270,000 less over a lifetime than the average joe.

Educators have tried to disrupt these patterns and strengthen career pipelines by building “work cultures” in school that expose students to new possibilities and on-the-job experience. In a 2018 study of children who grow up to file patents, economist Raj Chetty found that STEM programming by itself was not effective — apart from being born into affluent families, he observed, the biggest influence on whether girls became inventors was whether they lived close to women who invent.

“These findings suggest that there are many ‘lost Einsteins,’” Chetty said, “individuals who would have had highly impactful inventions had they been exposed to innovation in childhood — especially among women, minorities, and children from low-income families.”

“They set a model”

Studies of vocational and STEM-centered programs have been limited and offered little clear evidence of improved achievement for male or female students. One exception: a study of vocational high schools in Massachusetts that found that they improved graduation rates, especially among low-income students.

One of those schools, Minuteman High School, which serves 10 towns north of Boston, was named a National Blue Ribbon School in 2018. Fifty-one percent of its students have disabilities, and nearly one-quarter are considered economically disadvantaged, but 95 percent of students graduate in four years.

Minuteman is recognized by workforce advocates for its success in preparing female students for science and technical careers. The school runs a STEM camp for middle school girls in the summer and a high school camp during February vacation.

Every new student goes through what Principal Jack Dillon calls “an exploratory process”: immersion into each of the school’s 18 career majors, from plumbing and heating to robotics.

“We want to expose the girls to all the types of majors we have that maybe they didn’t know about,” said Dillon. “We want our girls to be in engineering, programming, web, biotechnology. We do a decent job trying to promote those programs.”

The soft skills of his female students has become both a selling point for middle school girls and a way to make the sale.

“We really used to take a higher proportion of males to do our presentations to other schools, but we switched that to a higher proportion of female students, because they set a model for the girls in the other schools,” he said. “It’s now about three girls to one boy [doing presentations]. Years ago, that was reversed.”

Disclosure: The 74’s coverage of the skills gap, the challenges and opportunities of better educating our future workforce, and efforts underway to improve local employment pipelines is underwritten in part by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)