Analysis: Banning All For-Profit Charters Without Considering Performance Would Be a Grave Mistake — Every Neighborhood Deserves a BASIS Education

Wasting no time in wooing the nation’s largest labor union, Democratic primary candidates have come out strong against public charter schools. Sen. Bernie Sanders led the pack with the most aggressive anti-charter stance, insisting that all charters abide by the union contracts in their local districts and calling for a total ban on for-profit charter schools. Not to be outdone, Sen. Elizabeth Warren recently rolled out an education plan designed to appeal to unions: It ends the main source of federal funding for charter schools and echoes Sanders’s call for a ban on for-profit charters.

Even more-moderate Democrats have been attempting to shore up teachers union support: South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg expressed skepticism that the expansion of charters could help improve public education, and he openly denounced for-profit charters, saying they have no place in the future of American public education. Former vice president Joe Biden, a man who served as second-in-command to arguably America’s most pro-charter president, said he did not believe in using federal funds to support for-profit charter schools.

On the surface, this middle-of-the road stance against for-profit charters seems noncontroversial. But most Americans don’t know that Arizona is the only state that allows for the creation of new for-profit charter schools. (California revised its law in 2018 to ban new for-profit charter schools.)

Charter schools are tuition-free, public schools open to all students. In terms of academic performance, they are held to the same state standards as district-run schools — or, if laid out in their charter, higher ones. Because they operate independently of a school district, however, charter schools have autonomy over staffing, budgeting, curriculum, school design and management structure.

While two-thirds of charter schools in the United States are freestanding and do not rely on a management organization, the remaining 2,500 public charters contract with a management organization to conduct operations that a district’s central office handles for traditional public schools. The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools describes a management organization as “an entity that manages at least three schools, serves a minimum of 300 students, and is a separate business entity from the schools it manages.” Charter management organizations are nonprofits, while education management organizations are for-profits.

CMOs are behind 25 percent of the country’s charter schools, while EMOs operate 12 percent of charters. Outside of Arizona, all charter schools, regardless of whether they have a contract with an EMO or CMO, have nonprofit boards, making the schools themselves nonprofit entities.

The question is: When Democratic candidates attack for-profit charters, are they distinguishing between for-profit schools and nonprofit charter schools that have management contracts with EMOs?

An even better question: Why are Democratic candidates focused on the tax status of a school’s management entity as opposed to the school’s academic outcomes?

Banning all EMO-operated schools without taking into account school performance would be a grave mistake, especially since the highest-performing, nonselective public schools in the country are managed by an EMO.

BASIS public charter schools

At a time when the U.S. has fallen behind its international counterparts academically, BASIS Charter Schools offer world-class education. The network serves about 19,600 students in Arizona, Texas, Louisiana and Washington, D.C. It consists of 27 nonprofit public schools of choice that contract with the EMO BASIS.ed, which provides curriculum, teacher recruitment and training, information technology support, human resources, financial and business services, accounting, and legal and student services. BASIS.ed charges the schools a management fee. Independent auditors regularly review the management fee paid by the schools and have concluded that it is “reasonable given the services.”

“Each school is governed by an autonomous nonprofit board of directors,” BASIS.ed CEO Peter Bezanson explained. “The board members have no connection to the EMO, which is an important safeguard because it allows them to make a decision about whether to use BASIS.ed as the company to manage the schools. That distinguishes us from our peers [in Arizona] that are for-profit schools.”

BASIS Charter Schools began in Tucson, Arizona, when Michael and Olga Block struggled to find a middle school for their daughter. Olga Block had been a dean at Charles University in Prague in the Czech Republic before coming to the United States. She wanted her daughter to attend a school that was internationally competitive in terms of rigor, student accountability and academic focus.

Having no luck finding such a program in Tucson’s traditional public schools, the two parents decided to start a charter school that prioritized content-area knowledge and combined the high academic standards of Europe and Asia with the American ideology of self-sufficiency. They recruited and selected teachers based on their subject-area expertise as opposed to their teaching certifications. In 1998, BASIS Tucson opened its doors to 58 students, including the Blocks’ daughter.

“They call us a for-profit management company, but really, we began as — and are — a family-owned business,” says Bezanson, whom the Blocks recruited five years ago when they stepped down as CEOs. “Being a family-run business is powerful because it allows us to be nimble and make changes quickly in a way that a nonprofit organization might not be able to do. We aren’t only concerned with returning investments to investors. We’re concerned with offering the highest-performance, highest-quality education available in the country. We’re focused on running the best schools in the world.”

The best schools in the world

In large part, the expansion of the network has occurred because BASIS Charter Schools offer a rigorous curriculum designed to produce internationally competitive students — an educational option that, in America, usually only comes attached to a price tag or mortgage.

While the reputation of BASIS Charter Schools goes far beyond test scores — the schools pride themselves on creating a culture where students respect learning, seek knowledge independently and develop a sense of self-efficacy — student performance on exams has far exceeded the performance of students at most U.S. schools.

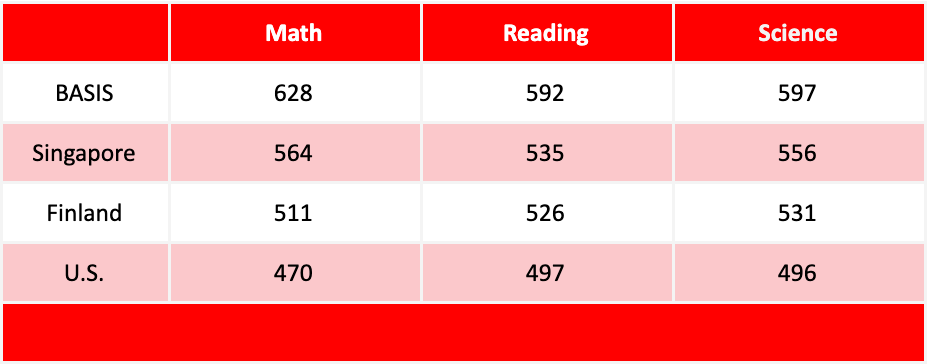

On the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Program for International Student Assessment — arguably the world’s most important international assessment — U.S. students consistently score below students from equally developed countries in Europe and Asia (such as Finland, Singapore and South Korea). Since 2000, the OECD has administered PISA every three years, and the U.S. has maintained an 18-year history of underwhelming performance.

However, on the OECD’s 2018 Test for Schools, an international exam based off of PISA, students at BASIS Schools outscored every other educational system in all three core subjects.

Results on the 2018 OECD’s Test for Schools

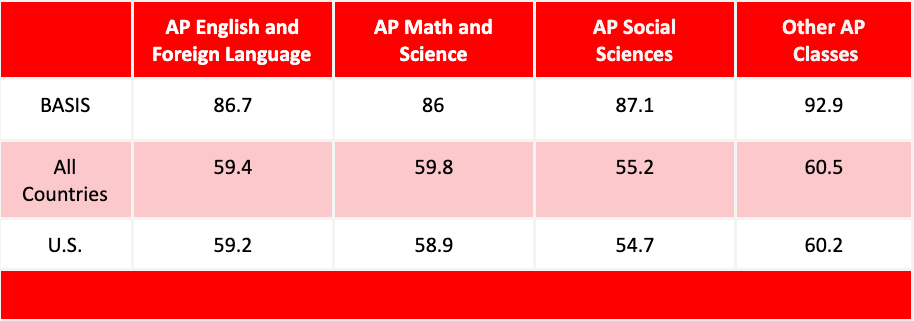

To receive a BASIS diploma, students must take seven Advanced Placement courses, sit six AP exams, and pass at least one exam with a 3 (out of 5) or higher. In 2018, the network had an overall AP exam pass rate of 85.5 percent, with an average AP exam score of 3.7. On average, a BASIS graduate will take 11.8 AP exams. Overall the percentage of BASIS Charter Schools students scoring a 3 or higher on their AP exams exceeds their peers both within the U.S. and abroad. The OECD also considers students who score at least at a level five out of six on the exam as potential “world class” knowledge workers of tomorrow. In math, 58.8 percent of BASIS students achieved a five or above, and in reading and science the percentages were 32.6 percent and 32 percent, respectively.

Percentage of Students Passing Exam With a 3 or Higher

Because they earn numerous AP credits, many BASIS graduates enter college as a first- or second-semester sophomore.

The BASIS model

In addition to a specialized and challenging curriculum, BASIS campuses have a unique instructional model. In first through fourth grades, students have a “learning expert” who accompanies them throughout the day to different classes taught by “subject area experts.” Students are exposed to higher-level subjects, including Mandarin, engineering, Latin, physics, logic, economics and chemistry, earlier than at most public schools. They can begin AP courses as early as eighth grade.

It’s an intentionally rigorous curriculum, and the network’s leadership team is unapologetic about it.

“The BASIS curriculum is not for everyone,” BASIS executive director DeAnna Rowe said. “But, for parents and students who want an education at this particularly unique level — and make no mistake, there are many families who do, indeed, want such an education — there is nothing like it.”

At the high school level, students finish all of the graduation requirements by junior year so that they can spend senior year focused on capstone courses, such as “history through film” or “infectious diseases,” that promote deeper, more creative thinking. Teachers often design the capstones based on their own passion and student interests. Because BASIS Charter Schools recruit teachers based on their subject-area expertise, it’s not unusual for teachers to have doctorates or other terminal degrees in their disciplines. Students respect their teachers, and teachers’ passion for content positively affects student engagement.

“[The] network’s greatest achievement might be the notion that we are here for any student that is willing to work hard — for any child that wants this sort of high-achieving environment,” Rowe said “You can’t find this at many other American schools, and not every student or family wants this sort of experience, but we will welcome and support anyone who wants it: anyone at all, no matter their previous academic or personal success or background.”

BASIS Charter Schools cast a wide net of recruitment strategies: social media campaigns, newspaper and radio advertisements, billboards and occasionally even street banners that contain information about how and when to apply. When opening a new school, it’s common practice for the staff to hold informational meetings in neighborhoods throughout the metropolitan area. Overall, the schools have racially diverse campuses; however, the number of socioeconomically disadvantaged students served varies significantly from campus to campus.

“We get accused a lot of cherry-picking students, and that’s false,” Bezanson said. “We don’t choose our kids; our kids choose us. We use a blind lottery system, with only a sibling preference, to determine admission. We don’t care where kids come from. We want to serve every single person who wants the education we have to offer, regardless of race, income or gender identity.”

The network serves a high percentage of first- and second-generation Americans, whose families come from all over the globe — from Mexico to Ukraine to China.

“A lot of these families find our education consistent with what they received as a youngster in their home country,” Bezanson said.

Many families — regardless of where they live — are seeking a public education that will educate their kids to the highest possible level. Network-wide, BASIS Charter Schools have 12,300 students on their waiting list. These families care about outcomes for their children, not the tax status of the school’s management organization.

“There’s obviously been a lot of pushback against public charter schools over the last few years,” Bezanson said. “I’d love for the people in power, both Republicans and Democrats, to understand what public charter schools have done to revolutionize educational quality in the U.S.”

Bezanson believes that what the charter sector needs most is high-quality authorizers that hold schools accountable for performance and revoke their charters if student achievement lags.

“A charter school should not exist unless its students are performing above average,” he said. “If we as a community of charters are vigilant about closing the low performers, we would solve a lot of our own problems.”

That’s something that Democratic candidates should learn from Bezanson. Rather than attempt to dismantle the charter sector, these candidates should be making progressive arguments based on school quality, seeking to improve the sector by demanding accountability for performance from both the charter schools and their authorizers. Threatening to ban the nation’s highest-performing nonselective public schools because of political ideology is regressive. Every child deserves access to a BASIS education. The goal of real progressive candidates should be to ensure that they get it.

A former English teacher, Emily Langhorne was previously the associate director of the Progressive Policy Institute’s Reinventing America’s Schools project.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)