A Huge For-Profit Charter Network Uses the Same Approaches as High-Performing Nonprofits. The Results Are Impressive

One of the largest for-profit charter school networks in the country, National Heritage Academies, produces substantial gains in student achievement compared to traditional public schools in Michigan, according to a major new study circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Unlike most research on charters, which have focused on urban schools serving largely minority and low-income student populations, it finds that improvements were mostly enjoyed by female, non-poor, and white or Asian students.

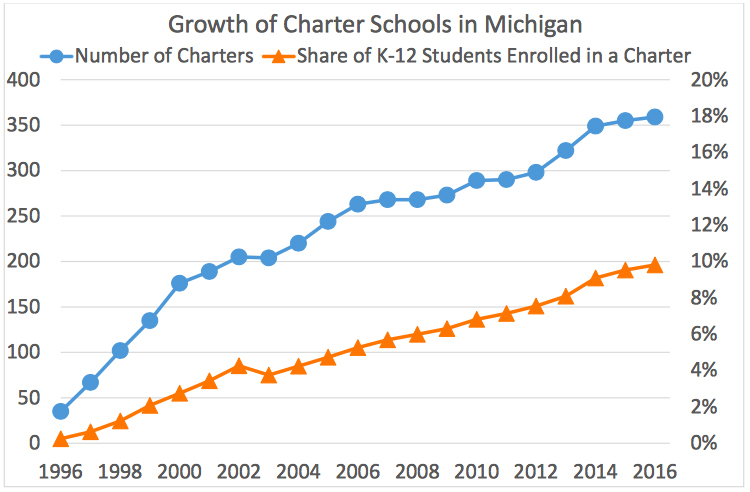

The study, conducted by noted economists Susan Dynarski and Brian Jacob of the University of Michigan, is thought to be the first to use charter lottery data to consider for-profit charters. The for-profit sector constitutes roughly 15-20 percent of charter schools nationally, though it has experienced significant growth over the last decade.

For-profit schools have found themselves in bad odor recently, with left-leaning school-choice advocates like former Education Secretary John King and Los Angeles School Board member Nick Melvoin calling for a ban on new for-profit operators. Standardized test scores at for-profit charters — especially the hundreds that operate online, which have come under special fire for substandard instruction and suspect finance practices — often lag far below nonprofit charters and traditional public schools.

The din has grown so loud that even longtime charter-friendly figures have revisited the issue. Chester Finn, a former Education Department staffer under President Reagan and president emeritus at the right-leaning Fordham Institute, has conceded that at the dawn of the charter movement, school choice boosters like him “wanted the infusions of capital and entrepreneurialism that accompany the profit motive, but we didn’t take seriously enough the risk of profiteering.”

The National Heritage Academies (NHA) are the fourth-largest for-profit network in the country (since many for-profit charters are predominantly virtual schools, they are technically the second-largest network of brick-and-mortar schools operating for profit), educating 56,000 kids in 86 schools spread across nine states. Roughly half of those schools exist in the chain’s home state of Michigan, the only state where for-profits make up a majority of charter schools overall.

Under the influence of longtime activist and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, Michigan has earned a dubious reputation as an under-regulated charter school market. Like DeVos, NHA founder J.C. Huizenga is a wealthy, politically connected native of Grand Rapids who has pushed to loosen regulations governing schools of choice. NHA now accounts for nearly half of all Michigan charter students enrolled between the third and eighth grades.

If the overall environment in Michigan might suggest cause for concern, Dynarski and Jacob’s paper tells a different story. Students at the 48 Michigan NHA charters — most serving grades K-8 — tend to perform better in math than those at nearby traditional public schools.

“Consistent with prior lottery-based charter studies, we find that an additional year spent at an NHA charter is causally associated with positive test score gains in math, with smaller effects on reading scores,” they write.

Existing research literature around charter schools, such as those written by economists like Roland Fryer and Caroline Hoxby, have found that urban charters sometimes outperform neighboring district schools dramatically. But charters in suburban and rural areas, home to a student population that is typically more white and less poor, haven’t been shown to beat results at district schools.

Since school placement isn’t random — families must take special steps to enroll their children in charters — these studies rely on data from admissions lotteries for oversubscribed charter schools. The lottery data allows researchers to compare otherwise-identical students who either won a charter school slot or else enrolled in a nearby district school. No study has used charter lottery outcomes to study for-profit charters until now.

Dynarski and Jacob used results from about 27,000 applications to roughly 750 NHA lotteries between 1999 and 2012. They then compared those results with student testing data from the Michigan Department of Education, which assesses both math and reading in the third and eighth grade.

The testing gains for NHA students are significant in and of themselves, but the authors also emphasize exactly who is achieving them. For-profit charter schools in Michigan, which comprise roughly two-thirds of all charters in the state, enroll proportionally fewer black students than nonprofits and are generally are less likely to be located in cities. But the difference at NHA is even more stark.

Between 2003 and 2015, NHA students were consistently more likely to be white (42.5 percent, versus 34 percent at charters overall), Asian (5.8 percent versus 2.9 percent), and Hispanic (9.2 percent versus 7.2 percent). They were less likely to be black (41.8 percent versus 54.8 percent) or economically disadvantaged (55 percent versus 71 percent).

“In contrast to most of the prior lottery-based charter impact literature which has consistently found that low-income, underrepresented minorities in urban areas benefit most from attending the lottery schools, the largest impacts of attending the NHA charter network are concentrated among non-poor students attending charter schools outside urban areas,” the authors write. “These findings further highlight the importance of exploring the full range of possibilities in the large, diverse charter school sector.”

Annual testing gains were nearly six times larger for female students than male, and more than twice as large for white students as black ones.

While they differ from many nonprofit charters in terms of setting and demographics, National Heritage Academies often mirror them in approach. As part of the study, Dynarski and Jacob administered a survey to hundreds of charter and traditional schools that were open during the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years. They found that NHA schools shared academic and organizational features common to high-performing nonprofit charters, such as higher parental engagement levels, extra instructional time in certain subjects, frequent low-stakes assessments, a “No Excuses” school environment, and ability grouping.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)