Aldeman & Marchitello: Skyrocketing Spending on Benefits Hurts Teachers and the Schools That Employ Them. 4 Steps Toward Fixing That

The frog in the pot never notices the water temperature rising until it’s too late.

This unfortunate metaphor is playing out in education policy. As Max Marchitello shows in a new report for TeacherPensions.org, employee benefits are slowly taking a larger and larger share out of school district budgets, leaving fewer dollars for students.

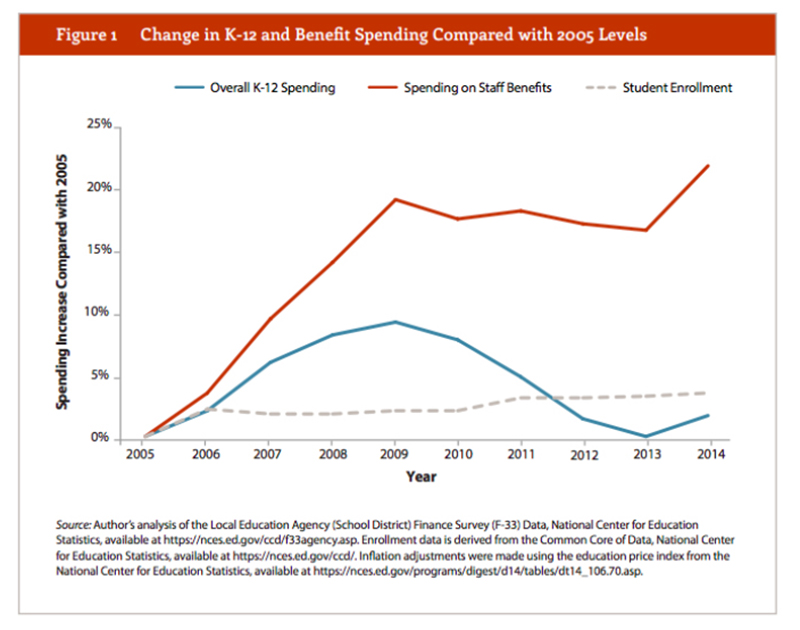

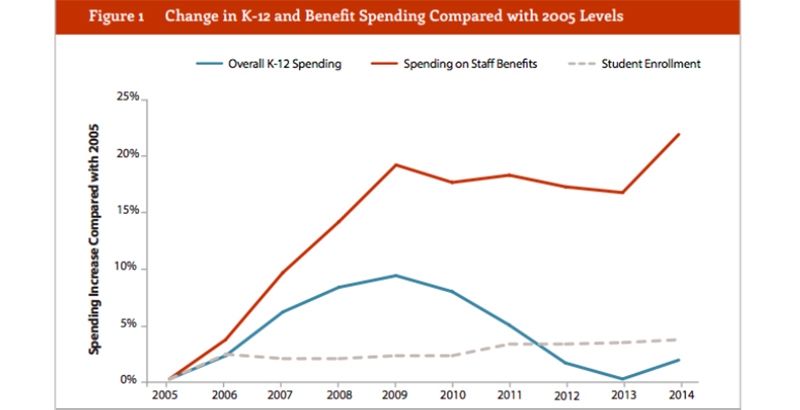

Nationally over the past 10 years, education spending on an inflation-adjusted basis went up 1.6 percent. In contrast, student enrollment rose 3.6 percent. And total benefit spending rose 22 percent. The result: a higher percentage of spending going toward benefits and fewer dollars going directly into classrooms.

This is probably not what teachers or the general public have in mind when they say they want to spend more money on education.

In new results released this week, Education Next found surging support for higher school spending overall and specifically for higher teacher salaries. And yet, when we talk about school spending, we are increasingly talking about employee benefits. For every $1 invested in instructional expenditures, school districts now pay about 26 cents for employee benefits. That’s up 4.4 percentage points, or 21 percent, just since 2005.

To put that in dollar terms, states and districts have collectively enacted a $7 billion cut in instructional spending. As the paper notes, “That’s comparable to cutting the main federal investment in education, Title I, Part A, by more than 40 percent. If Congress proposed slashing Title I by more than 40 percent, educators, parents, and community members across the country would inundate the Capitol with calls to protect the funds. And yet these cuts occurred quietly, state by state and year after year, and hardly anyone noticed.”

Of course, this wouldn’t be such a bad thing if the expenditures on benefits were making teaching a more attractive profession. But the costs are increasingly going toward paying off past debts, not funding benefits for current workers. Moreover, we have evidence that employees value $1 in salary more than they do $1 in benefits. As we’ve written before, teachers can’t pay their mortgages or their child care expenses with benefits. This dynamic plays out in the research literature, which finds that most teachers, other than those very close to retiring, do not respond to benefit incentives. Either teachers don’t know about the various rules affecting their benefit eligibility, or the incentives aren’t strong enough to make them change their behavior.

Add it all up, and we have an expensive system that doesn’t work well for employers or employees. So what is to be done?

The first step is recognition. Like the frog in the pot, nothing can happen until teachers and their representatives wake up to how benefits are squeezing education budgets.

The next step is to protect current retirees and near-retirees. They were promised certain benefits, they planned accordingly, and we as a society have an obligation to deliver on our commitments.

That still leaves existing pension and health care debts, which are owed to these very same teachers and retirees. There are some creative steps states could take to minimize those obligations, but policymakers also need to dedicate revenue streams to meet them. For too long, state and local policymakers have been able to pretend those expenses don’t exist, and they need to be honest about what those promises actually cost.

Finally, states should commit to more responsible benefit levels going forward. There are a variety of ways to share risks among employees and employers, but too often the public sector has put all the responsibility onto the employer. By and large, politicians have not managed that responsibility well, and those costs have trickled back to the employees in other ways, as we’re seeing now. School districts can’t confront rising health care costs alone, but there are cost-sharing or other mechanisms to strike a balance. Teacher retirement plans are typically determined at the state level, and adopting cash-balance or well-built defined contribution plans, and ensuring all teachers have access to Social Security, would go a long way toward restoring fiscal sanity.

Without such reforms, we don’t see how this trajectory ends. Teachers are already receiving smaller paychecks in response to rising benefit pressures. States have to turn off the metaphorical burners, or the pot will continue to boil.

Chad Aldeman is a principal at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of TeacherPensions.org. Max Marchitello is a senior policy analyst with Bellwether Education Partners. Bellwether was co-founded by Andrew Rotherham, who sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)