Aldeman: How Have Pension Costs Hurt Teacher Pay? If Contributions Were Still at 2001 Levels, Every Teacher Would Get a 7% Raise Today

Last month, I estimated that state and district spending on teacher pensions is up approximately 261 percent over the past 15 years. Meanwhile, average teacher salaries are flat, and teachers are rightfully mad about stagnant wages.

These things are connected: Teacher salaries are flat partly due to rapidly rising pension costs.

As an exercise to see just how much rising teacher pension costs have harmed today’s teachers, imagine a hypothetical world where pension contribution rates had been frozen at their 2001 levels. This isn’t entirely crazy. At the time, states were living high off the dot-com bubble while simultaneously cutting contribution rates to unsustainably low levels and enhancing benefit formulas. Nearly every state has subsequently been forced to reverse this trend by increasing contribution rates and cutting benefits.

But what if states had been more responsible and agreed to put any new money directly into teachers’ pockets, rather than making pension promises? How much would that be worth to the typical teacher today?

In this hypothetical world, states and school districts would be able to spend about $4,300 more per teacher per year, equivalent to giving each an immediate 7.2 percent raise.

But that’s not all — 37 states and the District of Columbia have increased mandatory teacher contribution rates into their state’s pension plan. That’s effectively a cut in teacher take-home pay, and it works out to an average of about $800 a year.

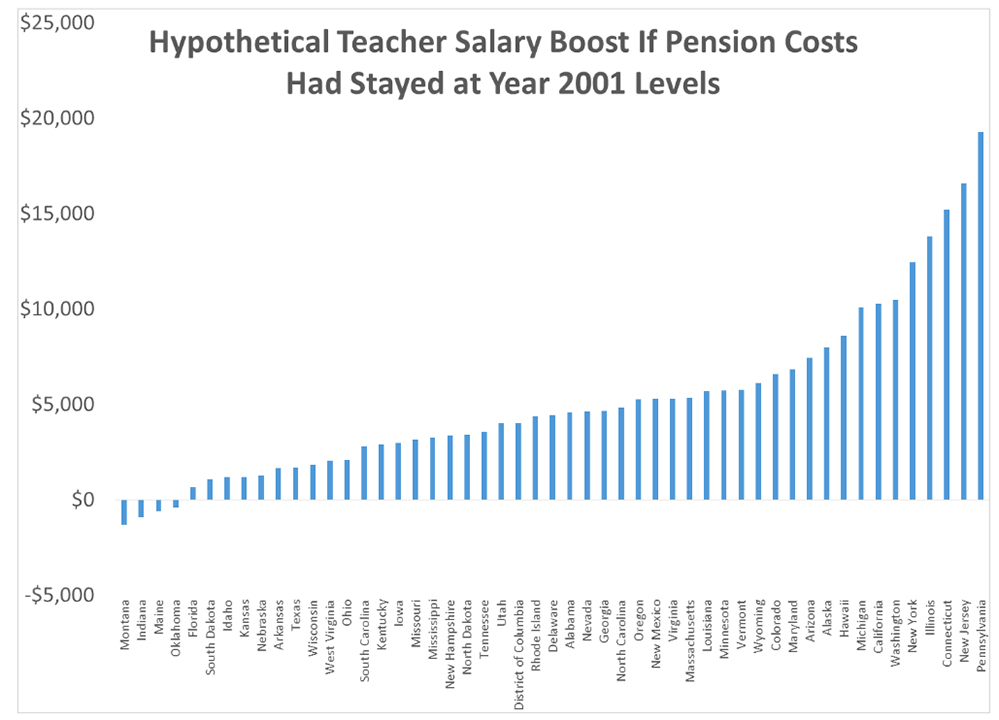

Add these two figures up, and it starts to look like real money. The graph below shows how much average teacher salaries could have risen if states had been more responsible with their pension plans. In that scenario, 36 states and Washington, D.C., could have boosted teacher pay by 5 percent, and 19 states could have given teachers more than 10 percent extra in compensation last year.

There are some extreme outliers on the right side of this graph, and Illinois, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania are known as some of the worst offenders in terms of adequately funding their teacher pension plans. A few states have kept their pension contributions at sustainable levels, and four states have actually seen their total actuarial burden fall. But consider New York, which is fifth on the list in terms of total dollar amounts. New York is often held up as a responsible actor because its teacher pension plan is reasonably well-funded, but it’s accomplished that mark in two ways.

New York’s state constitution provides that once a benefit is granted, it can never be taken away, so the state has cut benefits over time by opening new, less generous tiers for new workers depending on when they began their employment. Due to the constitutional protections, the benefit cuts affect only new teachers, but New York has also dramatically increased its pension contribution rates, and those costs affect everybody. New York teachers may not realize it, but they could have had a 16 percent bump in compensation if the state’s pension plan hadn’t been so volatile.

Now, these numbers are purely hypothetical, and they assume that states and districts would have spent the same amount absent their rising pension obligations — and that they would have invested all that money back into their teachers. But it’s a useful exercise to illustrate the harmful effects of pension cost increases.

Worse, these effects are largely hidden from teachers. Teachers may recognize when their own take-home pay gets cut, but they never see it when their state or their employer has to divert an increasing portion of their education budget to pay down pension promises. Those are education expenses too, but they don’t show up on teacher pay stubs, and they never make it into classrooms.

This exercise also helps illustrate the costs of the bargain that teachers have struck in recent years. Collectively, whether they know it or not, teachers have accepted lower salaries in exchange for the promise of future pension payments. At best, this deal works out only for the fraction of teachers who remain in the profession for their entire careers. But in reality, the costs of paying for teacher pension plans now outweigh even the highest back-end benefits awarded to long-term teachers. This is essentially a giant transfer of wealth from one generation to the next, and no current or future teacher wins from this arrangement.

None of this touches on the pressures teachers face throughout their careers. Teachers can’t use a future pension to pay for current child care expenses, mortgage payments, or other living expenses. Although the numbers presented above are hypothetical, teachers are struggling with the real consequences of this trade-off.

Chad Aldeman is a principal at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of TeacherPensions.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)