After a Decade of Gains, Latino Students Suffer Outsized Losses Amid Pandemic

Remote learning tougher for these children, who are more likely to attend an underfunded school, cope with a language barrier, have limited internet

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

After a decade of gains in academics and a marked boost in high school graduation rates and college attendance, Latino students suffered significant setbacks during the pandemic as many attended underfunded schools and had limited internet access at home, a new report shows.

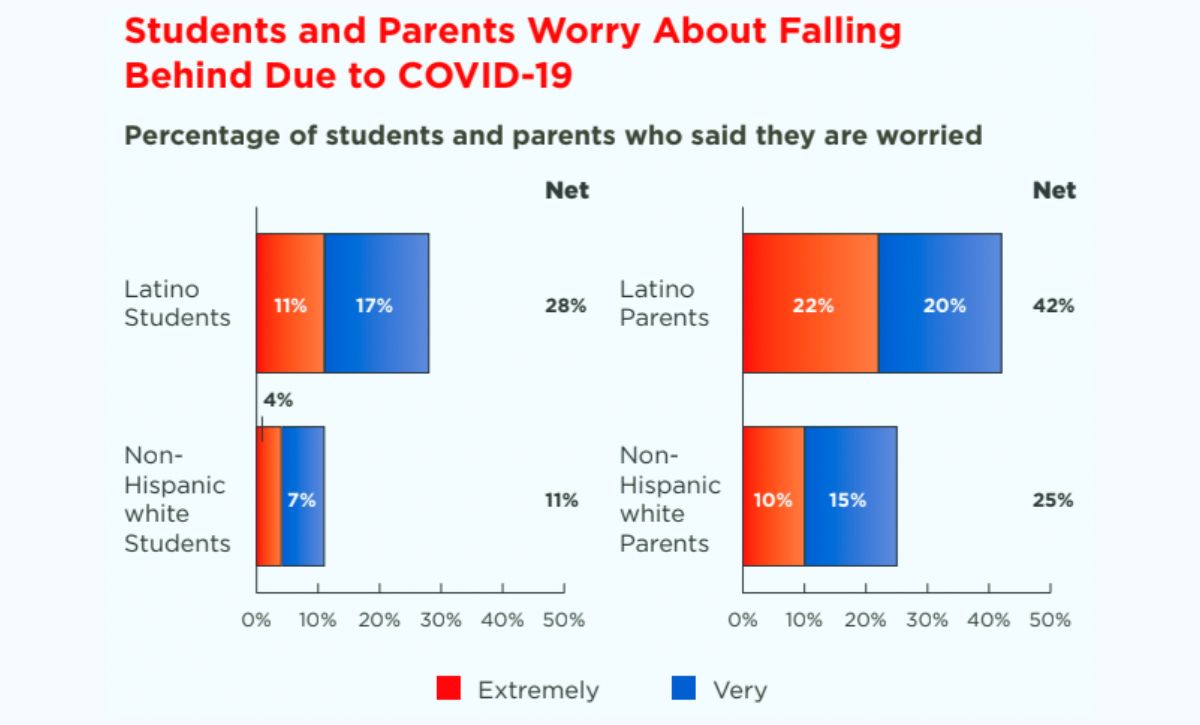

Some of these children also struggled with a language barrier — as did their parents — making the switch to remote learning even tougher, according to UnidosUS, the nation’s largest Hispanic civil rights and advocacy organization, which released the study July 11 at its conference in San Antonio.

“This report comes at a pivotal time as our schools and communities recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately impacted Latino students and their families,” UnidosUS president and CEO Janet Murguía says in the foreword. “We cannot allow hard won educational gains to be reversed, yet we also know that the pre-pandemic status quo was not working as well as it should.”

Latinos make up a formidable percentage of the K-12 population, growing from 9% in 1984 to 28% today. Some 94% of those under 18 are U.S.-born citizens and nearly three quarters are of Mexican descent. Despite stringent and sometimes hostile U.S. immigration policies, their numbers are increasing: Latinos are expected to hit 30% of the K-12 population by 2030.

First Lady Jill Biden, who spoke at the conference Monday, said the White House stands in support of the Latino community. She touched upon the gun safety laws brought about by the tragic shootings in nearby Uvalde, the diversity of the Latino population as a whole and the goals that unite this group.

“Yes, the Latino community is unique,” she said. “But what I’ve heard from you again and again is that you want what all families want. Good schools. Good jobs. Safe neighborhoods. You want justice and equality—the opportunity to build a better life for your families. It’s not only what all families want; it’s what all families deserve.”

Latino students have made substantial gains in recent decades on the education front, UnidosUS notes. Their on-time high school graduation rate increased from 71% in the 2010-11 school year to nearly 82% in 2018-19, an all-time high. Likewise, the number of Hispanic students enrolled in postsecondary programs jumped from 782,400 in 1990 to nearly 3.8 million in 2019, a 384% increase.

But both of these figures took a hit in recent years: The on-time Latino high school graduation rate dropped by .7% from 2020 to 2021, according to a data analysis from 25 states representing 57% of the student population. Even more troubling, Latino freshman enrollment in college shrunk by 7.8% in spring 2021 compared to the year before, marking the first such decline in a decade: The figure rebounded by 4% by the spring 2022 semester, UnidosUS found, but it remained below pre-pandemic levels.

The trend is in keeping with that of the overall college population, which is down by more than 1.4 million undergraduates.

Not all academic indicators are available and many poor students were not tested during the height of COVID, but at least one critical test shows a lag: Latino students in 3rd through 8th grade saw greater declines than their non-Latino white peers on NWEA’s Measures of Academic Progress, an interim assessment administered in schools across the country.

But, UnidosUS writes in its report, the loss needs to be put in context. Latino students were more likely to attend high-poverty schools that participated in remote instruction for a longer period of time, often yielding a greater rate of learning loss for students, the organization found.

UnidosUS recommends improved data collection and analysis meant to identify academic weaknesses and improve results. It implores districts to honor student’s rights to their education — some schools have been sued for failing to enroll immigrant students whom they feel will not graduate on time — and include the voices of students and their families in shaping education policies and services.

It also calls for a major increase in funding, a “bold and historical investment in Title III of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act,” the federal formula grant program intended to support English learners by increasing funding from $831 million to $2 billion.

“Since 2001, the population of English learners has increased by 35%,” the report notes. “However, Title III funding has not kept pace. When adjusted for inflation, funding has decreased by 24% since 2002.”

The group found Latino students are more likely than their peers to attend a low-rated school and to have a novice teacher. These children also have limited exposure to educators who look like them — just 9% of teachers are Latino — which is an important factor in student success.

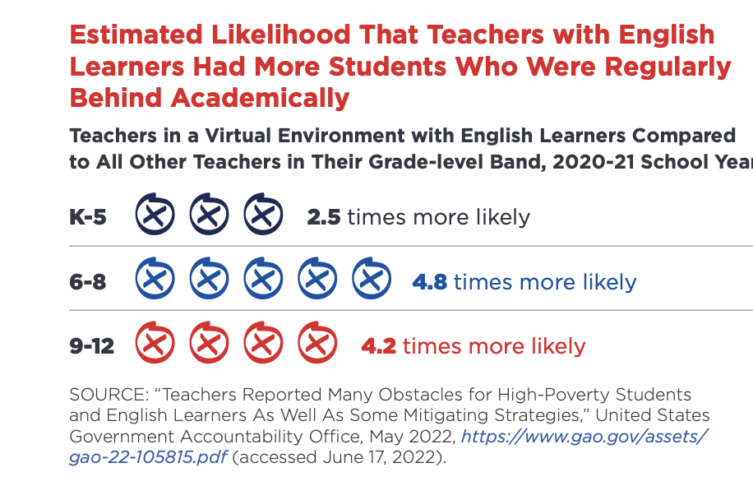

And language access remains a challenge: More than three quarters of the nation’s 5.1 million English language learners are Latino and a similar percentage speak Spanish at home.

Research shows students learning English typically make academic gains at rates similar to or higher than their peers, the study notes, but experience greater learning loss in the summer months when they are not in the classroom. The pandemic, which sent the nation’s entire school population home for months at a time, worsened this slide for Latino children, who were disconnected from their teachers and the technology their schools offered. Just two years prior to the pandemic, data shows nearly a third of Latino households lacked high-speed broadband internet and 17% did not have a computer in the home.

Despite many schools’ efforts to place a device in the hands of every child, Latinos remain at a disadvantage. Two years into the pandemic, 1 in 3 often or sometimes faced one of the following problems: They had to complete their homework on a cell phone, were unable to turn in their assignments because they lacked computer or internet access, or were forced to use public Wi-Fi to complete at-home work, UnidosUS reported.

And their lack of connectivity wasn’t the only problem, the group found: 50% of Latino parents reported having difficulty helping their kids with unfamiliar coursework and 58% had problems communicating with teachers, possibly because of a language barrier and schools’ failure to employ translators.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)