After Historic Declines in Math Scores, Schools Look to Bolster Summer Programs to Help Kids Catch Up

Flush with relief funds, districts are continuing robust summer efforts to help kids rebound in math. But the trend may soon derail as money runs out.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

School districts around the country, reeling from dramatic drops in fourth- and eighth-grade math scores on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress, hope to recoup at least some of what’s been lost through summer programs.

Flush with federal dollars, new and robust offerings have been open to a wide swath of students starting in the summer of 2021 and will continue in many districts this year. But the trend could stop as that pandemic relief money runs out.

Some districts, including Detroit’s, have already pared down summer programs, inviting only those students identified as struggling, while others can’t even reach all the children on that list — at least not during the summer.

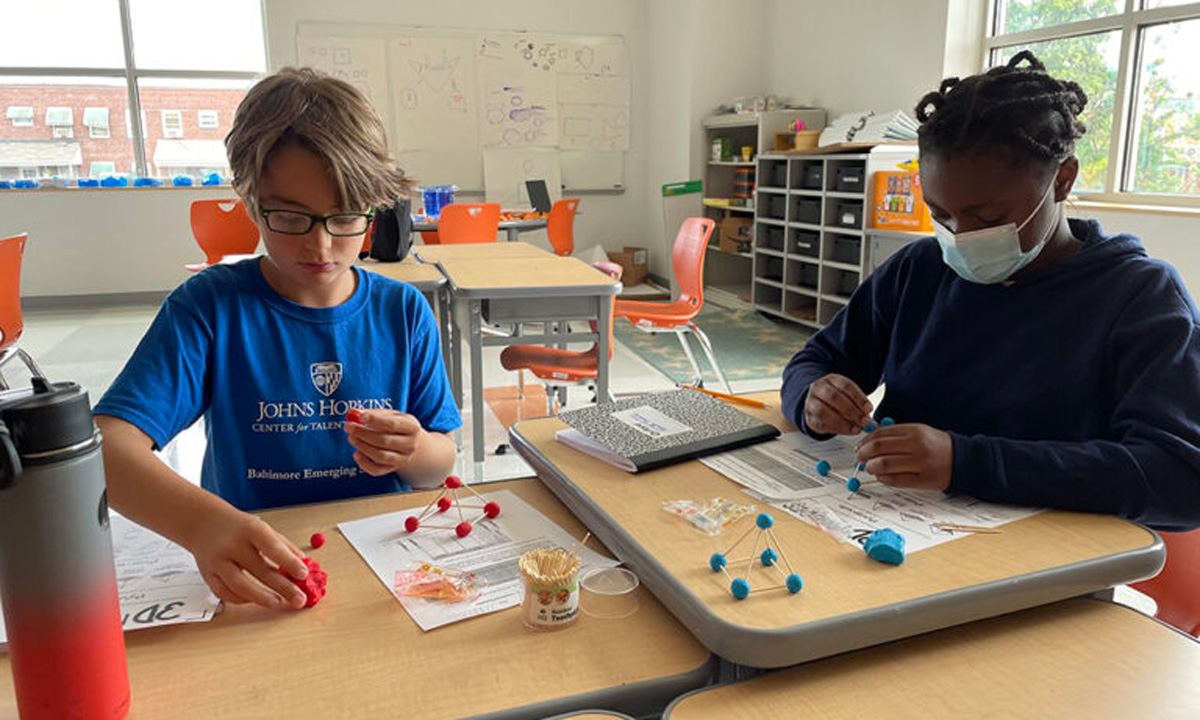

Baltimore City Public Schools saw some of the most staggering losses in mathematics at the fourth-grade level — a 15-point drop on the 2022 NAEP exams compared to those in 2019 — tying it with Cleveland for worst-in-the-nation.

Baltimore’s and Cleveland’s decline in fourth-grade math scores was nearly double the average eight-point drop among the 26 big city districts that took the tests and dwarfed the average five-point drop of fourth graders nationally.

Eighth graders in both cities also saw their math test scores plummet: They dropped nine points in Baltimore and eight points in Cleveland. These losses are on par with the rest of the nation: The major cities’ average and the national average for eighth grade math both declined by eight points.

The 76,000-student Baltimore district has been working for years to remediate those who have fallen behind. It offers extensive summer programming for children at every grade level — more than 22,000 seats from pre-K through 12th grade for summer 2023 programming, up by 2,000 from the year before, district administrators said. But only 15,000 children participated last year, meaning thousands of seats were left open.

And even with the additional slots, the number might not match the need as it relates to this subject: Just 7 percent of third through eighth graders tested proficient in math on recent state exams. At 23 Baltimore schools, not a single student tested proficient in math.

Administrators said their district’s summer program was developed, in part, in response to recent NAEP scores. But they know some children who might have benefited from the program will be left out because of budgetary restrictions.

“Of course, we would love to be able to offer every student an opportunity to engage in learning during the summer,” said Laurie-Lynn Sutton-Platt, director of summer and extended learning.

The upcoming program can’t be a catch-all, but it can help, district administrators said.

“It’s a start,” said Kerry Steinbrenner, Baltimore’s director of mathematics. “Summer is an ideal opportunity for students to continue to develop their math skills and we don’t want to miss that … We want to try to impact as many kids as we can during that time.”

Cleveland Metropolitan School District, which serves more than 36,000 children, is also working to undo damage done by the pandemic. Some 4,200 students are enrolled in its five-week summer learning program with more added to the list every day. The district hopes the figure will reach the height it did last year at 6,500.

But it can’t guarantee participation.

“We are working to reach all of the students we can during the summer, but it is dependent upon students and families electing to enroll,” said chief communications officer Roseann Canfora. “We cannot require them to do so.”

Although driven by poor reading, not math scores, some third graders in Tennessee are mandated to attend summer programming this year if they performed poorly on that portion of the state exam and are at risk of being held back.

In the long term, average math and reading scores improved for fourth and eighth graders on the NAEP between the early 1970s and 2012. Between 2012 and 2020, just before the pandemic struck, they largely flattened while achievement gaps between high and low scorers — a persistent equity issue with NAEP — widened. And then the unprecedented drop in the 2022 scores brought COVID’s impact into full relief.

How long it will take children to recover from that — or what it will take for more students to reach grade-level proficiency in math — are big questions, but recent research has shown the sharp decline in math proficiency could have lifelong negative consequences.

Talia Milgrom-Elcott, executive director and founder of Beyond100K, a national network focused on preparing and retaining 150,000 excellent STEM teachers in 10 years, believes wealthier children have long made up what was lost.

But others will never reach that goal, she said.

“What’s different isn’t the kids: It’s their experience during the pandemic and the support they’ve received since,” she said. “We could have corralled all our resources to accelerate the mental, emotional and academic recovery of all kids — and if we would have, we’d likely have created the next great generation — but we haven’t. At least not yet.”

The federal government gave schools $190 billion in COVID aid with $3 billion available for summer learning. Experts say the type and quality of the summer programming counts, while some researchers assert that even that unprecedented overall sum is not enough to reverse the level of learning loss.

Melodie Baker, national policy director at Just Equations, an organization that promotes math policies that support equity in college readiness and success, said students need engaging and meaningful content that helps them make sense of the material and retain what they’ve learned. This is true whether it’s delivered during the school year or the summer, she said.

“It’s also important to recognize the role of teacher diversity as a long-term strategy for improving student engagement and learning outcomes,” Baker said. “A diverse teaching staff can provide students with a range of perspectives and experiences that can enhance their understanding of the material and make it more relevant to their lives.”

Some 110,000 of New York City’s roughly 1 million students will participate in summer learning this year, a spokeswoman told The 74. NYC students slid nine points on the fourth-grade NAEP mathematics tests and four points on the eighth-grade exams.

One program, Savvas Summer Impact Math, will focus on grade-level instructional priorities for grades K-8, helping students build math foundations, fluency and conceptual understanding to support learning recovery, acceleration and enrichment, she said. It includes assessments meant to identify weaknesses and help teachers narrow learning gaps ahead of the upcoming school year. Other programs include project-based learning and financial literacy.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district, where fourth graders saw their math scores drop 13 points and eighth graders 11 on the 2022 NAEP exams, plans to grow its summertime math offerings for middle schoolers heading into ninth grade.

Mark Bosco, the district’s senior administrator for expanded learning and partnerships, said the four week-long program is expected to swell from 400 to 1,000 participants this summer.

“This is designed for students who find math abstract,” Bosco said.

Pre- and post-assessments reveal improvement: Children who stayed for the 16-day duration who could not answer a single pre-algebra question correctly at the start of the program could successfully answer five or six questions out of 20 at the end, Bosco said.

He described the summer program as hands-on and project-based. In one instance, he said, reflecting on last year’s program, students were made to go through the steps of finding and financing a car, learning about credit applications, compounding interest and loans.

“It really got them thinking about how math can be so important in everyday life,” he said. “The kids are applying concepts in pretty advanced ways.”

Chicago Public Schools is encouraging schools to implement math camps this summer for rising third and fourth graders in addition to programs for students in middle and high school, a spokesman said. Fourth graders in the district saw a 10-point decrease on math NAEP scores. The loss was worse for eighth graders, who suffered a 12-point decline.

More than 73,000 of Chicago Public Schools’ 322,100 students engaged in at least one summer program last year. Math enrichment at the district includes the Summer of Algebra and Math Camp programs. A group of elementary schools also will host a Computer Science/Engineering Camp for students in kindergarten through fifth grade.

Despite the success of some programs, funding remains a concern: Canfora, of the Cleveland schools, said federal COVID relief funds likely will not be available for summer 2024. Her district is building next summer into this fiscal year’s general fund budget, which will be submitted to the school board this month.

Aaron Philip Dworkin, chief executive officer of the National Summer Learning Association, said districts should always work to establish and strengthen relationships with outside partners to build better programs and to secure funding so they are not as reliant on federal dollars.

“What do you do when the money runs out?” he asked. “We will figure it out. Everyone will contribute what they can and we will make it work.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)