A New Playbook to Recruit Tutors: Tap Teachers in Training

Amid labor shortages, hiring from teacher prep programs could ‘unlock’ up to a half million new tutor candidates nationwide, experts say

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, Jan. 13

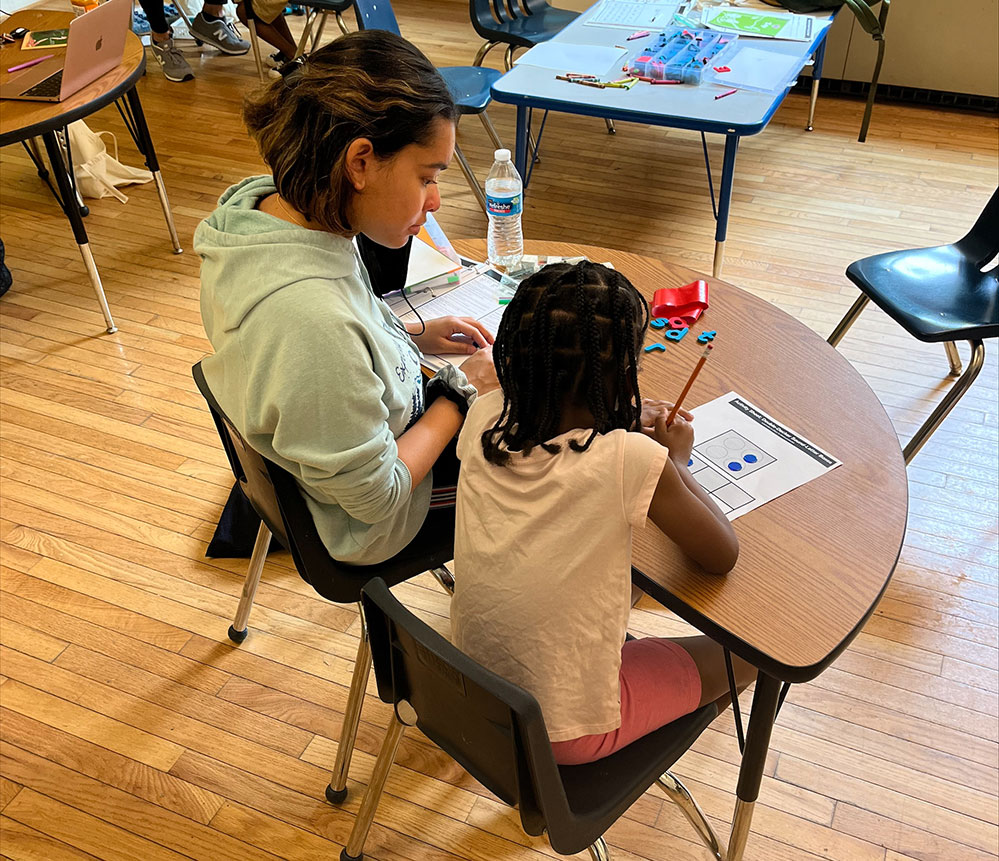

It’s 9:05 a.m. at Hendley Elementary School in southeast Washington, D.C. when Isabel Chae meets her first tutee of the day. The American University student pulls the first grader, who she describes as “so bubbly, so bright,” out of his classroom and the youngster asks to get a drink of water.

He sprints backward down the hallway to the fountain. “Please walk,” Chae calls from behind, unfazed by the boy’s surplus energy.

“I’m like, ‘OK, great. You seem like you’re in a frame of mind where you just want to be extra engaged with the lesson.’ ”

The college sophomore then appoints the student “Mr. Page-Turner” and makes sure to pause regularly during her read-aloud to let him decode words. During the writing portion of their lesson, she challenges him to print each word in a different color.

She’s honed these strategies over two semesters and a summer of work as a participant in American University’s Future Teacher Tutor program, a partnership between the college and DC Public Schools that seeks to boost below-grade-level readers. The 59 tutees who currently work with her and her peers progress about 25% faster in reading than the national average, according to pre- and post-tests administered by the university.

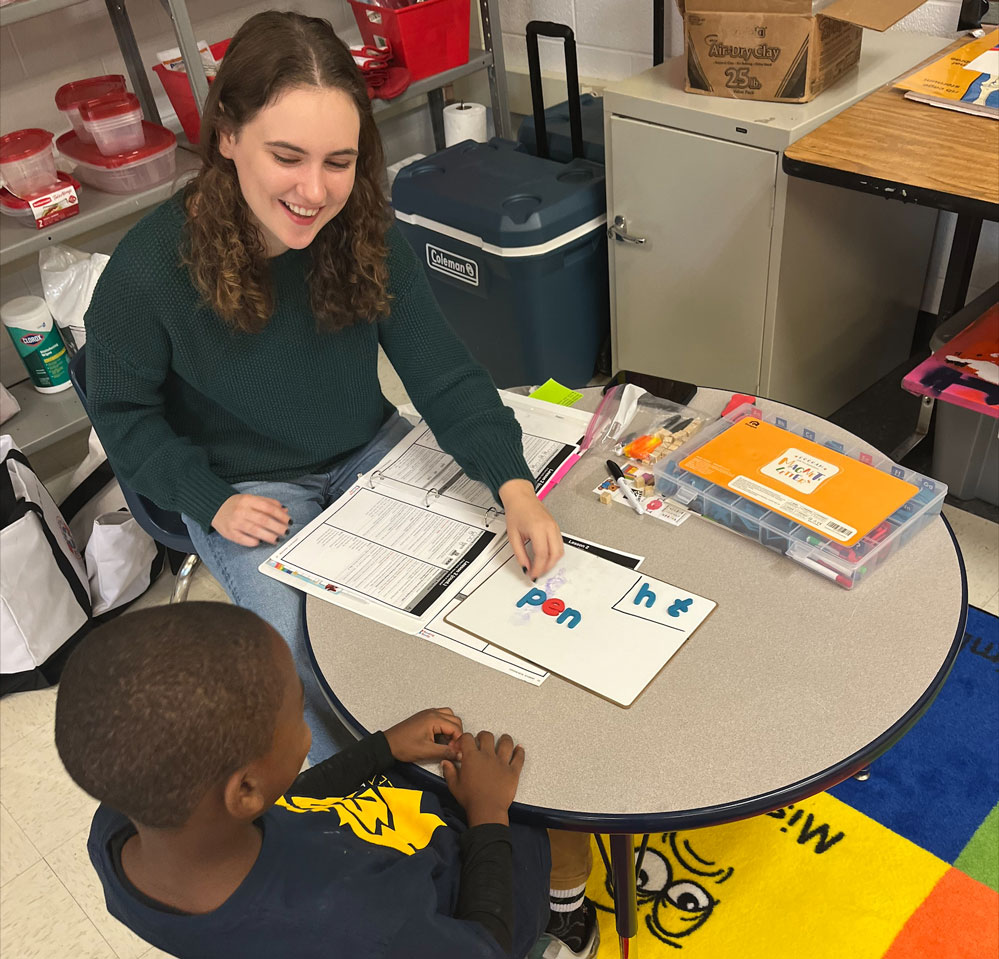

It’s a model experts say has the potential to help millions of K-12 students recoup learning lost during COVID. Researchers point to tutoring, either one-on-one or in small groups, as among the best proven methods for academic recovery. But school leaders looking to roll out such programs have often been hindered by educator shortages and pandemic fatigue.

Recruiting university students who, like Chae, are considering careers in education could “unlock” a huge new pool of human capital for the efforts, said Kevin Huffman, CEO of Accelerate, a nonprofit organization working to scale tutoring nationwide.

“There are more than half a million people at any given time who are studying to become a teacher in this country and very few of them tutor,” he said. At the same time, “you’ve got districts that need people and it just feels like a match that needs to be made.”

A win-win

Accelerate has distributed $10 million in grants to 31 tutoring initiatives across the country this school year, including $750,000 to Deans for Impact, a nonprofit working to bring teacher candidates into high-needs schools as tutors. American University’s Future Teacher Tutors initiative is one of the 22 programs in the group’s network, which altogether account for 900 tutors serving approximately 2,500 students across 13 states.

The model is simultaneously a way to “meet the very real needs of students and families [and] an opportunity to strengthen the way we prepare future teachers,” said Patrick Steck, policy advisor at Deans for Impact.

David Murray, program manager for the tutoring initiative at American, agrees that bringing pre-service teachers into local classrooms has yielded a “synergy” that has “been super beneficial, both for the tutors and the students.”

Normally, students in the school’s college of education would not gain classroom experience until their junior or senior year. But after a recent change, a course typically taken by underclassmen now requires tutoring as a service learning requirement. The majority of students in the Future Teacher Tutors program, which employed 21 undergrads this fall, come from that course, said Ocheze Joseph, director of education undergraduate programs.

“We decided that at American we wanted to … begin to engage our students in hands-on experiences working with students as early as their freshman and sophomore years,” the administrator explained. “The earlier that they are working with children, getting acclimated to the classroom environment, the stronger their confidence grows.”

To Chae, the idea of working as a lead teacher fresh out of college without the in-depth experiences she’s gained as a tutor seems “terrifying.” Now, having spent so much time working with students, she has realistic expectations. It will still be “somewhat terrifying,” she said, “but I know what I’m in for.”

All tutors earn over $20 per hour for their work and the program gives a stipend for transportation via Uber or Lyft, helping undergrads access K-12 campuses that are on the opposite side of the city. American University foots the bill thanks to literacy grants it received from the Office of the State Superintendent of Education via the agency’s CityTutor DC partnership and from the Benedict Silverman Foundation, who also provides the curriculum used by the tutors.

Most tutors work about four hours per week, but Chae works as many as 12, spending all day at Hendley Elementary on Tuesdays and Fridays. All told, the college sophomore feels she’s “paid very well” and is “given a lot of support.” She and her peers engage in regular training sessions to hone their tutoring skills and meet weekly with a program coordinator.

Scale and sustainability

Still, the program at American University only reaches a tiny fraction of the D.C. students in need of tutoring, a difficulty that’s plagued similar initiatives in other districts and states as well.

Youth nationwide saw historic backslides in reading and math during the pandemic, with some of the most severe losses for students living in poverty. Researchers say academic recovery efforts have not yet matched the scale of missed learning.

“The puzzle is how you take [tutoring interventions] to a large scale,” Huffman said.

He thinks that’s where Deans for Impact can step in, figuring out how to replicate initiatives like the one at American. The 22 tutoring initiatives already in the organization’s network exist within a universe of roughly 2,100 educator preparation programs nationwide. It’s the “most obvious, glaring hole in the human capital pipeline for tutors,” said the Accelerate CEO.

“People who already want to become teachers, they should all be tutoring students as part of that work. … It would reach millions of kids,” he said.

It’s a vision that Steck, at Deans for Impact, sees as especially urgent on the heels of the pandemic, but also necessary for the long term. Though many districts are now funding learning recovery efforts with federal stimulus dollars, his organization is seeking to lift up financially sustainable models that can operate even after relief funds dry up in 2024.

A central question is: “How do we make high-quality tutoring something that doesn’t just exist in the context of COVID relief efforts … but something that is a standard part of how we support students and communities?” he said.

At Hendley Elementary, Chae sees the benefits in real time for her six tutees.

One of the first graders she works with began the year not knowing all the letters of the alphabet. She would tune out of her literacy lessons because she was frustrated. Now, the girl “lights up” when it’s time for tutoring and persists even when she has difficulty sounding out the words — a trait Chae knows can spell gains far into the future.

“She will sit there and plug away at it. … And I’m like, ‘You’re super close.’ And she consistently gives that little extra bit of effort just to get the word, which is fantastic to see.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to Deans for Impact, Accelerate and The 74. The Overdeck Family Foundation provides financial support to Accelerate and The 74. The Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies and the Joyce Foundation provide financial support to Deans for Impact and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)