A Decade After It Promised to Reinvent Teacher Prep, Relay Is Producing a Much-Needed, More Diverse Teaching Corps

As far as he was concerned, Harrison Gaskins wasn’t a teacher.

It was the 2017-18 school year, and he was a paraprofessional at KIPP Vision Primary, a charter elementary school in Atlanta. He worked one-on-one with a student, and he did it well. Then, during his first year, Gaskins’s colleagues named him Teacher of the Month.

The accolade got Gaskins thinking, and soon his supervisor was encouraging him to get his master’s degree and become a classroom teacher, a possibility that hadn’t crossed his mind back when he was a student.

“I only remember four male teachers and none of them were black, none of them looked like me, so I never even thought, ‘I can do this,’” Gaskins said.

Gaskins enrolled in the Relay Graduate School of Education as part of a low-cost, two-year residency program intended to help people who already work in schools, career changers and recent college graduates become classroom teachers. Since its launch less than a decade ago, Relay has had success rare among graduate schools of education in recruiting teaching candidates of color and male and black male candidates in particular. Nearly 10 percent of Relay’s students are black men, for example, five times the percentage of such teachers nationally.

Gaskins said the program helped him work through feeling “intimidated” and “a little fearful” about attending graduate school.

“The intentionality of explaining how much they invest in you as an individual” made a difference, he said. “I really felt security in the amount of support that I had.”

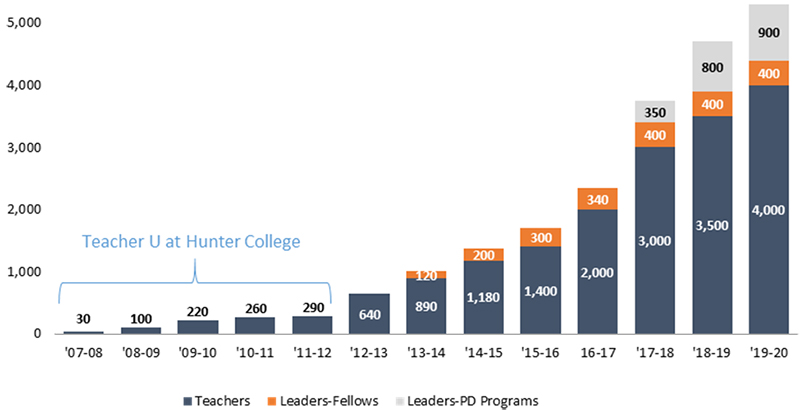

Since launching nearly a decade ago, Relay has seen its enrollment soar from about 290 to more than 4,000, plus an additional 1,300 school leaders, while expanding from one location to 19 nationwide. All the while, Relay has targeted its recruitment among undergraduate students, race-based student groups and mid-career professionals to ensure some of the most racially diverse groups of faculty and students among graduate schools of education across the country. Forty-five percent of Relay’s faculty identify as non-white, compared with 24 percent at postsecondary institutions nationwide, and 66 percent of its students identify as people of color, compared with 25 percent of students in postsecondary teacher preparation programs nationwide.

The groundwork for Relay was laid in 2007 by founding president Norman Atkins, who also started the Uncommon Schools network of charter schools. The program incubated at Hunter College as Teacher U, and then, in 2011, it became the first stand-alone graduate school of education in New York state to open in more than 80 years. From the beginning, it was poised to offer a radically different graduate school experience for prospective educators. As a New York Times story described at the time, Relay would have “no courses,” “no campus” and “no lectures.”

Relay’s focus was on helping its part-time graduate students — many of whom were full-time classroom teachers through Teach for America and other alternative teacher training programs — support the students in front of them each day. Accordingly, the Relay program emphasized practical, actionable skills to support classroom management and student engagement, not content knowledge or instructional theories, as is more common in traditional teacher preparation programs.

Relay now recruits a wider range of students and, at least according to one measure, provides them with top-notch preparation. The National Council on Teacher Quality, which has been critical of the quality of the vast majority of teacher preparation programs (and received criticism in turn), ranks Relay in the 94th percentile nationwide.

Rob Rickenbrode, who until recently oversaw the organization’s rankings, said Relay has managed to control for quality as it has served more and more graduate students. In 2017-18, nearly 1,000 students earned a certificate or a master’s degree from Relay.

“They’ve been able to keep a very tight hold as they’ve expanded and do a really excellent job in their student-teaching experience,” he said.

Yet Relay’s attempt to rethink the graduate school of education experience has also attracted scorn. More than half of the teacher preparation programs in New York City tried to block Relay from opening back in 2011, arguing in part that it would increase competition. And Relay’s close ties to charter schools — KIPP and Achievement First were also involved in its founding, and their leaders sit on Relay’s board — have also attracted criticism.

Ken Zeichner, a professor emeritus of education at the University of Washington, has long questioned the quality of graduate schools of education generally and Relay in particular. He’s opposed Relay’s reliance on Teach Like a Champion, the book of teaching techniques authored by Doug Lemov of Uncommon Schools, and what he described as Atkins’s “demonization of university [led] teacher preparation.”

Within the past year, Zeichner said, he met with Mayme Hostetter, who became Relay’s president in 2018, and says he has seen progress, but he remains concerned about the lack of empirical evidence of the program’s effectiveness. The page on Relay’s website dedicated to “Impact,” for instance, cites figures such as the percentage of graduates over the past six years who stay in the classroom as teachers (more than two-thirds) and the nearly 90 percent of alumni who say Relay increased their likelihood of remaining in the classroom.

Zeicher said his criticism also applies to the diverse students whom Relay recruits.

“They need to be able to show, not just that 60 percent of their teachers identify as people of color, but what happens to them,” Zeichner said. “If they can show that they can prepare people of color who can be retained [as classroom teachers], I think that’s a positive thing and we need to learn from that.”

Zeichner’s openness to learn from Relay on this front stems in part from the paucity of racial and gender diversity among candidates in a field where 77 percent of teachers are women and 80 percent are white. Research shows that students are less likely to drop out of school and more likely to aspire to go to college, among other effects, when their teachers look like them. This is especially true for black male students, even if they have just one black male teacher. The issue has attracted attention from 2020 presidential candidates; Sen. Kamala Harris said at the September debate that she would invest $2 billion in teacher prep programs at historically black colleges and universities, if elected.

In an interview, Hostetter, who started as a founding Relay staff member, said having diverse faculty and students was all the institution has ever known, and attributed that to its roots in New York City and its primarily serving urban school districts. Yet there’s more to Relay’s success with diversity. According to data from the U.S. Department of Education, Relay has greater racial and gender diversity than its primary teacher preparation peers in New York City, such as Bank Street College, Fordham University, Teachers College and Hunter College.

Hostetter said Relay has concentrated more in recent years on both faculty and graduate student diversity. Many of the deans at Relay’s campuses in places like Connecticut, Louisiana and Houston are people of color, and Hostetter said having such representation at the staff levels and beyond can produce a virtuous cycle.

“One thing I’m proud of [that] we’ve done at Relay over the last decade, from our inception really, is to show people what great teachers look like, whether that’s in videos or the faculty member in front of their classroom or meeting on their campus,” said Hostetter, who formerly taught at KIPP, among other schools. “We are showing people that great teachers are not just 80 percent white women. I think there’s a huge diversity in the group of people who are excellent teachers in this country. So I think when you show people who great teachers are, what great teachers look like, and then you ask them to join their ranks, you are making a pretty compelling invitation.”

Formally making the invitation to potential recruits are Alia McCants and her eight-person national recruitment team. Most of the team concentrates on particular regions of the country, and they keep an eye on mid-career professionals like Gaskins who are already in education but not leading classrooms (and are more likely to be non-white and bilingual), a strategy known as district in-reach. In addition, two team members focus on historically black colleges and universities like Dillard University and Morehouse College, while one works with Hispanic-serving institutions.

At all colleges, McCants said, the goal is to recruit students before they reach their senior year. Her team is interested in all majors — students studying communications and psychology would “make great teachers,” she said; “they just don’t know it yet” — and partners with specific student groups, like black student unions. They aim to compel the students to go into education and, ideally, attend Relay. McCants said her team is candid with prospective candidates about race and the benefits of attending a program with a diverse student body.

“There’s something about going through the residency [with a group of students who may share parts of your identity],” McCants remembers telling two black men who are teaching this year in New Orleans. “Even if you’ll be the only [black man] in your school, you won’t be the only one in your program, and especially if you’re coming from an HBCU, that’s a very comforting feeling. You’re never alone.”

Such support was reassuring, said Gaskins, the kindergarten teacher. The first topics he and his classmates studied as Relay students were not instructional strategies but sensitive subjects like race and socioeconomic status. He said students gathered in groups based on similar race and gender to discuss their motivations for teaching. Once the different groups shared their takeaways with one another, Gaskins said, they realized how much they had in common.

These types of experiences helped Gaskins believe he chose the right program, one that will help prepare him to make teaching his career. His path to the classroom was not linear — he previously worked as a behavior specialist at a program for at-risk youth, which he described as “dark” — but as he looks back, Gaskins thinks his past helped pave the way to his future.

“It kind of reminds me of Lion King,” Gaskins said, invoking his favorite movie. “Simba, he had all the potential to be king, but he had to go off and live with Timon and Pumbaa for a little while before he came back. So that’s what I feel like, maybe I had to go out and do some other things before I could really take care of Pride Rock.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provide financial support to Relay Graduate of Education and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)