New Analysis Shows Milwaukee’s Religious Schools Now Overwhelmingly Enroll Voucher Students

Milwaukee’s school voucher program, a pioneering private school choice initiative launched nearly three decades ago, has profoundly altered the landscape of religious education in the city, according to a new analysis from The Wall Street Journal. Since parochial schools were first allowed to accept voucher students in 1998, they have come to represent the vast majority of schools participating in the program. The paper also found that most have transitioned to serving a predominantly voucher-bearing clientele alongside a shrinking minority of full-pay students.

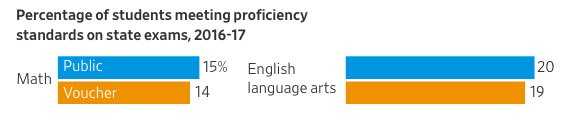

That’s not an auspicious development, given the authors’ other principal finding: The higher the percentage of voucher students in a school, the lower the students’ performance on standardized tests of math and English.

While the highest-performing voucher schools tend to limit the portion of students receiving the subsidy, some 81 of 120 total schools are now composed of 75 percent or more voucher students. State test scores for the voucher sector have not been found to improve upon those for area public schools, though one study has found that Milwaukee students using private school vouchers were more likely to graduate from high school and enroll in four-year colleges.

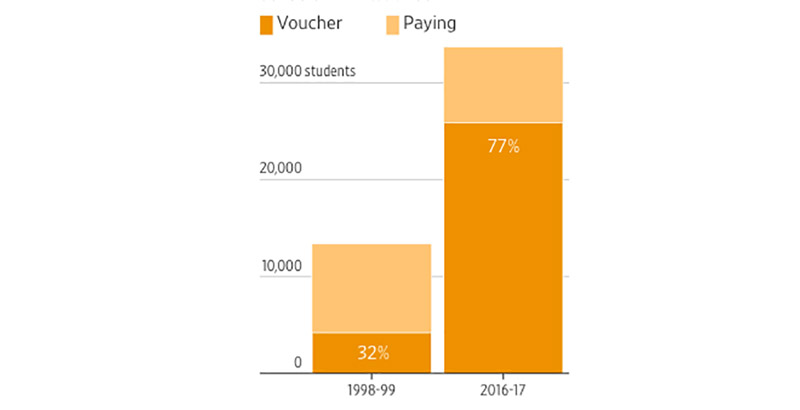

When Milwaukee’s landmark program began in 1990 with just a handful of private academies, religious schools were barred from participating, and no school could enroll more than 49 percent voucher students. But that mandate was dropped in 1995, and the state’s Supreme Court ruled soon after that religious schools should also be permitted to accept the state-issued vouchers. Beginning in the 1998–99 school year, those religious schools constituted a strong majority — 64 of 83 schools, or 77 percent — of total participants in the initiative.

Their numbers have grown substantially in the years since, both in absolute and relative terms. Of 120 voucher schools in Milwaukee, 109 of them (over 90 percent) are religiously oriented, Journal reporter Tawnell Hobbs found.

Religious schools’ disproportionate presence in the voucher system can be explained by simple economics, observers say. With parochial school enrollment persistently sliding nationwide over the past half-century, major churches (in Wisconsin, mostly Catholic and Lutheran) have been grateful to accept state-sponsored tuition for thousands of new students. Although numbers are still down, the pace of enrollment decline among Catholic schools has slowed in recent years.

The intervention of government authorities in the fortunes of religiously affiliated institutions has naturally provoked constitutional concerns about the separation of church and state. But if civil-liberties advocates fret about the co-mingling of government and religion, worshippers also have cause to consider what impact state subsidies will have on their schools. As religious schools have rushed to take advantage of vouchers as a revenue opportunity, families paying full tuition have sunk to a distinct minority. In 30 such schools in Milwaukee that have continuously accepted voucher students since they were first allowed in 1998, the total percentage of full-pay students declined from 72 percent to 19 percent as the years passed.

Those enormous changes in demographics have brought a change not only to parochial schools but also to the faith communities that sponsor them. A 2017 study circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that Catholic churches that run voucher schools now receive more revenue from those vouchers than from their own parishioners.

That allowed them to ward off church closures and consolidations, the researchers found, but at a price: With the growing financial dependence on vouchers comes a downtick in church donations and spending on non-educational activities. The churches were spared from further diminishment, but in a meaningful way, their spiritual agenda was narrowed, the study found.

In classrooms, large contingents of voucher students were not associated with impressive academic results. Though families with incomes over 300 percent of the poverty line are now eligible to receive the subsidy, vouchers were originally designed to allow low-income children to escape from Milwaukee’s most troubled public schools. Many, if not most, voucher students, therefore, receive their voucher once they’re already several grade levels behind — then start work at a private school that exhibits nearly as much concentrated poverty as the public school they’ve just left.

While the Wall Street Journal analysis cites several high-performing schools serving almost exclusively voucher students, the best-regarded private schools in Milwaukee tend to put a cap on voucher enrollment. In a review of standardized testing data for 108 of the 120 local voucher schools, the authors found that those scoring in the top 25 percent for either English or math tended to enroll no more than 54 percent voucher students.

Scholars like the Century Foundation’s Richard Kahlenberg have long argued for socioeconomic integration as a key for lifting academic performance for vulnerable children, and a 2010 study of low-income students in Montgomery County, Maryland, found that they achieved much higher math scores when educated in classrooms with more affluent peers.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)