18 Years, $2 Billion: Inside New Orleans’s Biggest School Recovery Effort in History

Hurricane Katrina destroyed 110 New Orleans school buildings. How to upgrade them while honoring their architectural importance and historic heritage?

By Beth Hawkins | September 24, 2024In July 2023, 18 years after Hurricane Katrina left most of New Orleans underwater, NOLA Public Schools hosted a ribbon-cutting at the last school building reconstructed in the wake of the storm. On hand was a Who’s Who of people involved in the largest school recovery effort in U.S. history.

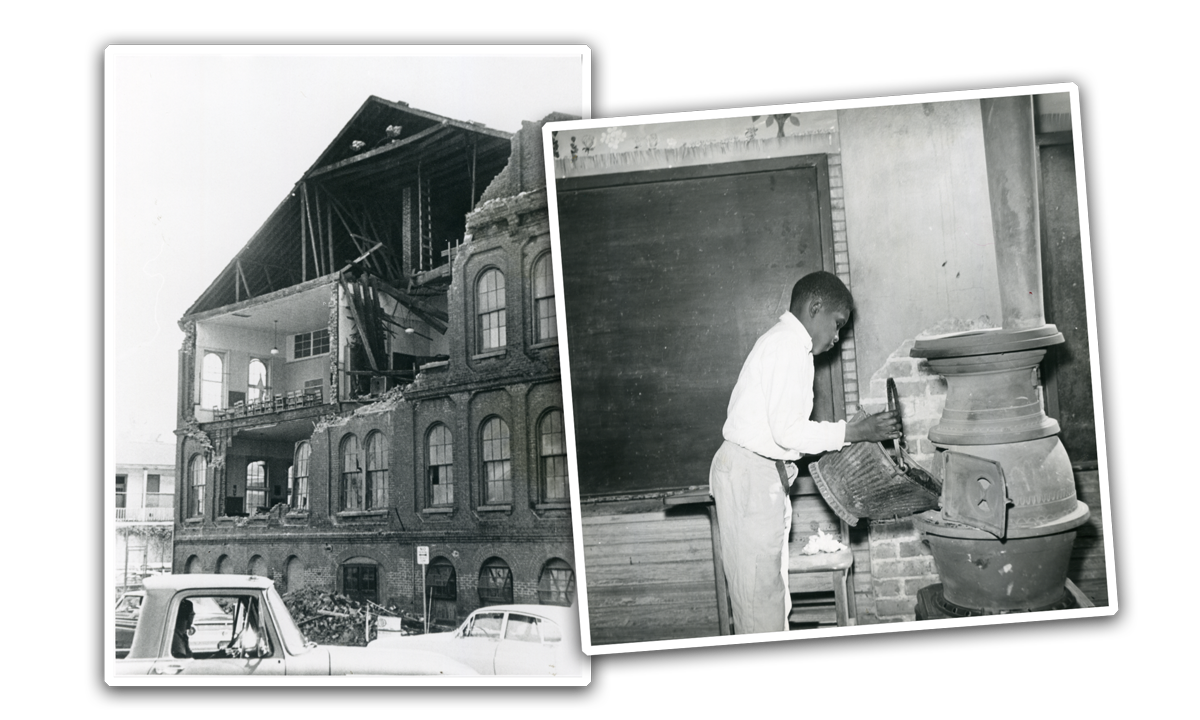

The 2005 hurricane and subsequent flood destroyed or severely damaged 110 of the 126 public school buildings operating at the time. Bringing them back was a linchpin of efforts to rebuild the city. Displaced families could not return until there were classrooms to welcome their kids.

The logistical challenges of the $2 billion effort were unprecedented. No one had ever tried to rebuild an entire school system. The Federal Emergency Management Agency was mostly in the business of repairing or replacing houses and residential buildings, and was notorious for doing so excruciatingly slowly.

Federal law specifically prohibited taking advantage of a disaster to build something better than what had been destroyed. Decades of official neglect, however, had left most New Orleans schools moldering long before the storm. Students sat in classrooms that didn’t meet fire and electrical codes, lacked window panes and were inaccessible to people with disabilities.

Adding to the challenge were New Orleanians’s passionate attachments — some generations old — to the legacies of individual schools, as well as the city’s racialized education history. Strict historic preservation rules protected elements of devastated buildings that needed wholesale upgrades. Officials would have to decide how to handle dozens of buildings that were the sites of important firsts — the first school for Black children, the first named for a Black community leader, the first to be forcibly integrated.

Officials quickly realized they would need to rebuild in three overlapping phases. First, on a ridiculously compressed timeline, they needed to construct or rehab a handful of schools so neighborhoods could start to revive. Then, they would have to determine which buildings should be torn down and which — and how many — replaced. Finally, they would have to figure out which could simply be refurbished and which historic — and often protected — landmarks merited a painstaking rebirth.

It was a massive, hydra-headed puzzle — but also a milestone. “For years, people have commented on the unacceptable physical condition of our schools,” then-Louisiana Superintendent of Education Paul Pastorek said in 2007, as he announced the rebuilding plan. “We want these schools to stand as a symbol of the value we place on our children and their education — and as a symbol of what’s possible for the future of our city.”

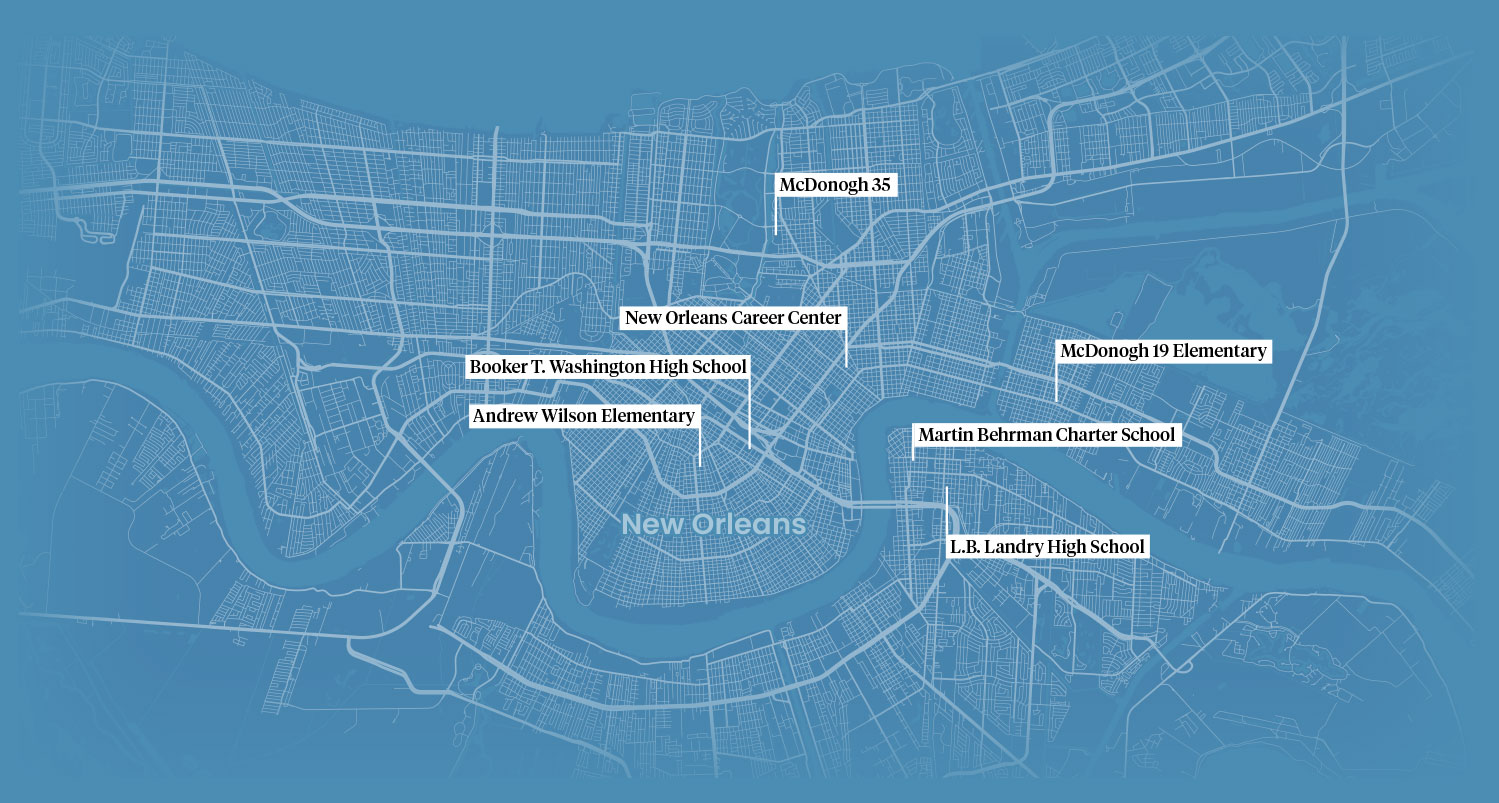

Here are the stories of seven buildings, each illustrating a different aspect of the 18-year effort.

Click the arrows for details on each building.

McDonogh 35

New Orleans’s first public high school for Black students is still its crown jewel

For decades, New Orleans’s location made it an ideal slave-trading hub, allowing a particularly aggressive enslaver named John McDonogh to become very rich. When he died in 1850, he willed the fortune he had amassed buying and selling hundreds of people to the city, decreeing that it be used to do the unthinkable: finance the creation of public schools open to children “of both sexes of all Classes and Castes of Color.”

The schools opened with his money all bore his name, distinguished from one another by sequential numbers. Opportunities for Black children came and went, though, until 1917 — when a group of African Americans persuaded school leaders to convert McDonogh 13, whose white students were being moved into a new facility, into the first public high school for Black students. McDonogh 35, as the building was rechristened, became — and remains — the city’s crown jewel, boasting generations of graduates who rose to prominence in politics, civic leadership and the arts.

The basic bargain — moving Black children into a dilapidated facility when white children were given a new one — persisted for the better part of a century. During that time, McDonogh 35 occupied four buildings. Each bore the same name and number — an unusual and historically significant protocol that persisted until the racial upheaval that followed George Floyd’s murder in 2020.

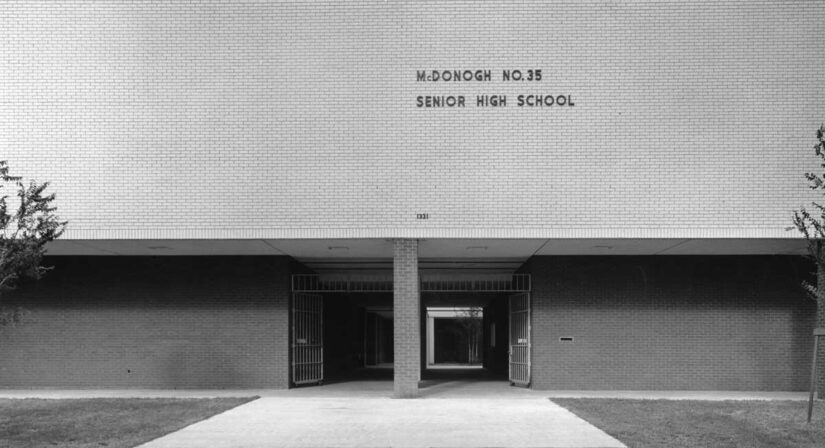

The original McDonogh 35 building was destroyed by Hurricane Betsy in 1965. Classrooms were then set up in an old courthouse. In 1972, it got a new, squat cement block building erected using a Tulane University design for bunkers.

The third McDonogh 35 came through Katrina in decent shape — which made the building an essential part of the reconstruction campaign. It reopened within a few months. But as the Orleans Parish School Board and the state Recovery School District began making a master plan for rebuilding the entire school system, planners realized the best use of the windowless facility was as a swing space — temporary quarters for a succession of schools whose own buildings were being replaced or rehabbed.

In 2015, McDonogh 35 got a gleaming, modern facility of its own. In 2020, the school board — which has the power to rename the buildings, though not the schools they house — dubbed the new building 35 College Preparatory High School. But McDonogh 35’s historic name remains because of its importance to the community. Today, it is the only school left that bears the enslaver’s name.

Finally, the architects and engineers turned their attention to the fate of the school’s old, bunker-like building. As it happened, the onetime home of the first Black high school would be the site of the last of 89 reconstructions.

L.B. Landry High School

A gleaming, not entirely practical, palace — built around an old magnolia

Displaced families could not move back to New Orleans until there were classrooms for their children. Because the flood had decimated many neighborhoods, the first few schools needed to be reopened in different portions of the city, so that as many communities as possible could welcome residents back home. In 2007, local and state education officials announced a plan to reconstruct five schools — one in each of the city’s electoral wards — as quickly as possible. With classrooms to welcome children distributed throughout the city, refugees from Katrina could begin returning to New Orleans.

L.B. Landry High School was not originally among the first five. Even before the storm, its neighborhood, Algiers, had more schools than it needed. Controversially, the “new” New Orleans was projected to be smaller. The building, which was moldering even before Katrina and dealt a death knell when FEMA used it as a staging ground, was unsalvageable.

Enraged, Landry’s alumni fought fiercely to bring back the school — the city’s second high school for Black students, the first on the west bank of the Mississippi and named for a revered Black physician. They won.

It took three years of pitched public battles, but a plan emerged, and it was clear the new Landry had to be a lot of things. It had to echo the layout of the old Landry. In contrast to the ugly, squat building it would replace, it had to be sleek and modern, a down payment on a different future.

Its design had to be complete in five months. After that, construction had to start right away and could last no longer than 20 months. It had to be hurricane-proof, its electricals and other critical infrastructure housed on the third floor — far above any floodwaters — and protected by exterior cladding able to withstand 125 mph winds.

Finally, because the community was determined to salvage something from Landry’s old campus, it had to be built around the only thing spared by the wrecking ball: a magnolia tree.

Completed in 2010 at a cost of $55 million, the new school is a soaring three-sided U built around an enormous magnolia. Inside is space for a health clinic, a community theater and classrooms that could be used by a local community college or university to hold classes in the somewhat isolated neighborhood.

At the back of the courtyard, three stories of windows illuminate a soaring atrium. They reveal a sweeping staircase leading up to a broad hall painted with social justice quotes in yellow and orange. Catwalks cross overhead, connecting the wings of the schools. The space glows, signaling the importance of the school to the community.

It’s beautiful, but dogged by design flaws, the school’s leaders say. It is impossible to get a mechanical lift onto the staircase’s landings, for example, so changing the bulbs that cast the golden light requires building a temporary two-story scaffolding, which can cost $12,000.

As Landry was being reopened, officials still needed to address the neighborhood’s excess school capacity. In 2013, the state Recovery School District combined a rival high school, O. Perry Walker, located just a mile away, with Landry in the new building. The district renamed the building housing the consolidated schools Lord Beaconsfield Landry-Oliver Perry Walker College and Career Preparatory High School.

Landry boosters howled again, but this time to no avail. That changed in 2020, in the wake of the George Floyd racial reckoning, when the district redesignated 27 schools that had been named for Confederate leaders and enslavers. Noting that Walker had been a district superintendent who reinforced segregation, the school’s operator changed its name back to L.B. Landry High School.

Andrew Wilson Elementary

Seamless wasn’t the goal in joining old with new

One of the first five schools rebuilt, Andrew Wilson Elementary originally consisted of five structures located in the Broadmoor neighborhood, a designated National Register Historic District. The main building was the only part of the school not too damaged during Katrina to rehab.

Deemed to have architectural significance, the facility was beautiful — but without its outbuildings, nowhere near large enough to meet the demand from returning families. Officials decided to restore the original building and to add onto it.

Opened in 1922, the original L-shaped building is a mashup of styles, drawing on Spanish Colonial, Classic Revival and Italian Renaissance designs that incorporate copper gutters, ornate rafter tails and high ceilings atop transom windows.

As was typical of New Orleans schools designed at that time, the main entrance was in the middle of the front façade, on the second floor. (The first floor is often referred to as the basement.) To reach the double doors, students walked up two staircases that fan across the front of the building in an inverted V shape. At its top, the front door opened onto a wide hallway leading to the office, located behind an expanse of mullioned windows.

Today, visitors walk past the façade, lovingly restored, and around the corner to a new, modern main entrance that sits at the place where the old building meets the new one. To the left of the new entry, an interior staircase climbs up what had been the old building’s end wall. From the landing at the top, two hallways branch off at right angles.

The old one, a wide path of polished wood, leads to the main office and sun-drenched classrooms beyond. The other is a long terrazzo hall that passes through a new L-shaped building, past a library, gym and lunchroom, among other modern spaces. The joined structures — one with a red tile roof and one corrugated steel — form a rectangle that surrounds a courtyard.

Both wings are beautiful and functional, but the places where Andrew Wilson is most visually interesting are the seams. At the top of the new stairs that lead to the office, where the addition meets the original structure, the ornate, curved wooden eaves of the old building extend out into the new space, covered by the roof of the newer wing.

The space covered by the old and new roofs is bridged by three stories of windows that look out onto the new courtyard. On the second floor, it houses a cozy, sun-drenched reading nook. Opposite is the door to a spacious, modern library.

The windows that previously let light into the rooms at the end of the old building now frame an illustrated timeline of the surrounding community dating to the 1500s, tracing Louisiana’s admission to the Union, America’s 1815 defeat of the British in the Battle of New Orleans and Broadmoor’s slow evolution from a lake to a diverse, middle-class neighborhood that prizes its education legacy.

McDonogh 19 Elementary

In the shadow of a breached levee, a civil rights icon turned her school into a museum

Six years after the Supreme Court handed down Brown v. Board of Education, a frustrated federal judge gave a recalcitrant Orleans Parish School Board a deadline for taking a first step toward integration: Nov. 14, 1960.

That morning, federal marshals escorted four Black first graders — born the year Brown was decided — into two all-white elementary schools. Most famously, Ruby Bridges was led into William Frantz Elementary School, in the Upper Ninth Ward.

Simultaneously, in the Lower Ninth, 6-year-olds Leona Tate, Gail Etienne and Tessie Prevost were walked past a mob hurling epithets and rotting fruit, up 18 steps and through the front door of McDonogh 19. As the girls entered the building, their white classmates left, never to return.

The McDonogh 3, as they would come to be known, attended school alone for a year and a half — joined only by the U.S. marshals protecting them and the protesters who showed up every day. For their safety, the windows were papered over and recess was held in the auditorium.

Desegregation orders notwithstanding, in 1962 the school board declared McDonogh 19 “for the exclusive use of Negro children.” The girls went on to integrate another elementary school, and then different middle and high schools. For 50 years, whites continued to leave for suburbs and private schools.

Katrina’s floodwaters first breached levees perilously close to McDonogh 19, which had just closed to students because of changing demographics. The storm devastated the neighborhood, which has yet to recover. Eventually, it became clear there was no real possibility McDonogh 19 would reopen as a school. It did, however, have tremendous value as a historic landmark.

After the storm, Tate, a postal worker, set out to buy the building, name it after herself and her classmates and turn it into a civil rights memorial. However, the Orleans Parish School Board was prohibited from selling it. Undaunted, Tate formed a foundation and spent nine years negotiating a deal.

The district eventually transferred ownership to the city housing agency, which was able to sell it to Tate and a community development group that specializes in the “adaptive reuse” of historic sites. The agreement called for creating 25 affordable senior apartments on the second and third floors.

To generate the $16 million needed to buy and renovate the building, Tate pulled together 60 funding sources, ranging from corporate donors to affordable housing tax credits. The TEP Center — TEP for Tate, Etienne and Prevost — opened in May 2022.

Visitors now enter not via the iconic staircase the girls and their marshals used, but through a door at its base. One flight up, the original main entrance is ringed with artists’ renderings of what the hallway will look like once Tate has raised the $5 million needed to complete the museum portion of the property. The intent, she says, is for visitors to feel what it was like for a first-grader to walk into the school.

The halls branching off from the school’s office are behind glass walls. Everything in front of the dividers is protected by the landmark’s 2016 inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. Behind the walls are classroom doors, which actually open onto apartments. A mural on the back of the building depicts the McDonogh 3 as both girls and women.

Downstairs, the classroom where the girls spent their days contains a single, child-sized wooden desk. It’s not original — the flood spared nothing inside the building. It’s placed there as a stark visual suggestion of what it felt like to be one of the three first graders, day after day.

Booker T. Washington High School

A new school built around an auditorium where history was made

In the early 1900s, with just a handful of Black public schools in existence, New Orleans’s African-American residents began a decades-long push for a vocational school. Fearing job competition, whites objected. Despite securing a $125,000 grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund — a philanthropy backing construction of Black schools throughout the South — the district stalled. For decades.

Thanks to the federal Works Progress Administration, Booker T. Washington Senior High School finally opened in 1942, built on a toxic dump. It quickly became a crucial venue where groups pushing for a better education for Black children could meet.

For years, its 2,000-seat auditorium — designed by the architect who drafted the eclectic plans for Andrew Wilson Elementary — was the largest space in the city for Blacks to congregate, making it an epicenter of the community’s artistic and political lives. Paul Robeson, Mahalia Jackson, Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles and Dizzy Gillespie were among the artists who performed at the school. Martin Luther King Jr. preached there.

A history of the school compiled by the African American High Schools in Louisiana Before 1970 blog catalogues numerous meetings of civil rights groups in the auditorium, including the 1945 annual assembly of the NAACP’s local chapter.

“With nationally known figures in attendance, the organization delivered a powerful message to the community in which it outlined its goals for the Blacks in America,” the history notes, quoting the Times-Picayune newspaper.

“Specifically, at this meeting the NAACP called for ‘the right of franchise, better housing conditions, equal education and economic advantages, and opportunities to serve community police and fire departments’ for all New Orleans’ African-American residents.”

Despite having fallen into disrepair, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Within two years, however, enrollment had dwindled from 1,600 to fewer than 400 students, and Booker T. posted the lowest test scores in the state.

After Katrina, the building sat vacant and decaying for seven more years before everything but the historic performance space was torn down. In 2015, alumni backed by the KIPP charter school network lobbied to have a new high school built around the auditorium.

Figuring out how to construct a state-of-the art facility without running afoul of historic preservation rules took years. The school’s alums, who refer to themselves as Washingtonians, had to work with multiple bureaucracies, including the National Park Service, to iron out everything from cleaning up the old dump to installing modern technology in the auditorium without disturbing its protected features. Completed in 2020, the new Booker T. Washington cost $55 million.

The renovated theater includes a sweeping, two-tier balcony covered by a gently curved ceiling punctuated by ornate tile. The tile reappears in the lobby — which doubles as a student health and dental clinic during the school day — and in the original entry vestibule, where Art Deco scrollwork has been preserved.

Because of quirks in how the rules are written, the auditorium by itself no longer qualifies for historic status. Even the smallest details were faithfully restored, in accordance with preservation guidelines. But the loss of the surrounding building meant the school no longer met the National Register’s requirement that the site’s “context” also survive.

Boosters still say the decision to replace everything but the auditorium was the right one. At the end of the process, the alumni association, state Recovery School District and KIPP produced a documentary detailing the school’s history.

Martin Behrman Charter School

Bringing a school into the 21st century when nearly every detail is untouchable

The restoration of what is now called Martin Behrman Charter School Academy of Creative Arts and Sciences was one of the hardest of the rebuilding campaign. Individual elements of the structure ranging from huge, multi-paned windows to teacher mailboxes are specifically protected.

Because of this, the renovation was expensive — at $40 million, it cost more than many of the district’s completely new schools — and painstaking. The complexity is one reason that the restoration was the second-to-last completed, with the school reopening to students in January 2023.

Located a stone’s throw from Landry, Behrman’s Spanish Colonial Revival building might be the most beautiful of the renovations. Built in 1931, it was heralded as one of the city’s finest facilities, with then-cutting edge spaces such as laboratories and equipment for home economics courses. Now, it serves students from preschool through eighth grade.

By the time Katrina hit, its modern sheen had faded. The building was too small to house everything needed by a contemporary school.

The renovation challenges are visible from the street. To one side of an ornate, three-story entrance is a bell tower. Though no one seems to remember why, the clock was dismantled during World War II, rebuilt in 1997 and in disrepair when the renovation began. To restore it, the renovators called on White’s Clock and Carillon, a company that specializes in restoring clock towers.

To get inside, visitors pass through a security gate in a tiny vestibule — a sub-optimal design decision forced by the original floor tile inches beyond it, which can’t be touched. Nor can the detailed plasterwork in the lobby — or, for that matter, the plain plaster on the walls.

Also protected: huge wooden windows, tile mosaic floors on the second and third stories and ornamental molding in an auditorium that rivals Booker T. Washington’s. A balcony adjoins a spacious room that teachers use for breaks and prep, but it’s uncomfortably hot most of the year and there is no allowable way to put up an awning or pergola for shade.

There was no way to create the spaces needed by the school’s early childhood education program, such as a tiny restroom in each classroom, in the protected building. So designers built an annex across the street that houses a gym, cafeteria and eight kindergarten and preschool classrooms. While the work took place, classes were held in one of the school system’s swing spaces, a school that was minimally functional but slated for permanent closure.

Martin Behrman’s leaders were ready to move in the second the last coat of paint was dry. Students went home for the 2022 holiday break from the school’s temporary home, the old Oliver Perry Walker facility that was merged with nearby Landry. When they came back a couple of weeks later, it was to two completely outfitted buildings.

In 2023, the reconstruction project was recognized with the Louisiana Landmarks Society’s Award for Excellence in Historic Preservation.

Dr. Alice Geoffray High School/New Orleans Career Center

New Orleans’s last school rehab capitalized on a charmless bunker’s good bones

In total, between 2005 and 2023, the Orleans Parish School Board and the state Recovery School District constructed or rehabbed 89 buildings, 32 of them wholly new. Apart from the unprecedented engineering, architectural and equity challenges, officials had to figure out where schools would hold classes while their permanent homes were being rebuilt.

Sometimes that meant FEMA trailers. Other times, a school community would use a swing space — a building in good enough shape to be habitable but not a gem. The windowless cement box built in 1972 for the school system’s pride and joy, McDonogh 35, was one such space. As the end of the reconstruction campaign approached, planners turned their attention to its long-term fate.

At the time of the building’s design, Hurricane Betsy’s devastation was still fresh. Accordingly, the structure was constructed using Tulane University plans for creating fallout shelters, which gave it a feature most people would not stop to consider: the sturdiest foundation in the district. That made it uniquely suited to house not a school per se, but a center that could provide career and technical education to students throughout the district.

In addition to its literal strength, the school had a huge concrete courtyard, spaces big enough to accommodate heavy equipment and a decent electrical grid. With some work, it would make a perfect high-tech career training facility.

And so the old McDonogh 35 building became Dr. Alice Geoffray High School, home to the independent, nonprofit New Orleans Career Center. Louisiana has a high need for workers who have strong skills but not necessarily a four-year degree. Training programs for welding, robotics, health care and similar jobs are in great demand but too expensive for individual high schools to offer.

A wing dedicated to health careers has functional hospital beds, nursing stations and exam rooms. Welding bays have been built in a cavernous space on the ground floor. A spacious, second-floor commercial kitchen for culinary arts trainees is located near a service elevator so food can be delivered to a bank of walk-in coolers.

Throughout the building, the mechanicals are exposed. Trainees, as students are called, can work on exposed water pipes, electrical panels, heating and cooling equipment and IT infrastructure. The central courtyard is still open, but it has a roof and a fan so would-be carpenters and other tradespeople-in-training get early exposure to working in Louisiana’s climate.

Lastly, the bunker-like building got windows. Lots of windows.

Layout by Eamonn Fitzmaurice and Meghan Gallagher

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter