Lessons From a Global Reckoning: Students at a Revered New Orleans HS Learn the Hard Truth About the Slave Trader School Is Named For. Most Other Kids Never Do

This is the second story in a six-part series, “Lessons From a Global Reckoning,” in which The 74 examines how issues of race are taught — or ignored — in America’s classrooms. As the pandemic continues and after nationwide protests following the death of George Floyd, this series seeks to take a hard look at how educators are tackling these painful but important issues. Read the rest of the pieces as they are published here.

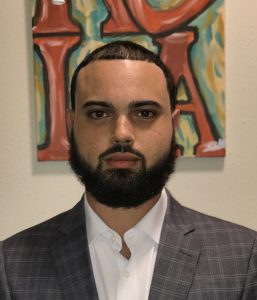

When Donald Hess tells his students that their New Orleans high school is named for a man who amassed a fortune trading slaves, their reactions are typically swift, starting with disbelief and turning quickly to anger.

Wow, I didn’t know that.

Why didn’t anybody tell me that?

Why hasn’t anybody changed the school’s name?

Hess tries hard not to influence his students’ emotions, which in his experience are the fuel that will propel them to connect the answers to those questions.

No one tells Hess’s juniors and seniors about John McDonogh before they find their way to his classroom because most Louisiana schools teach only very basic information about slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction — and precious little of it involves the way that brutal legacy shaped their communities.

“It’s just the basic, ‘Blacks were slaves, slavery was bad, here’s a couple of Black people who did good,’” says Hess.

Walter Stern, a New Orleans native and University of Wisconsin-Madison professor who authored a biography of McDonogh, says the slaveholder’s legacy and the way it shaped the schools is a “perfect vehicle” for teaching about the city’s history. “He provides a window into showing both how deeply entrenched white supremacy and the subjugation of Black New Orleans has been,” says Stern, “as well as how Black New Orleanians have used the power available to them to create institutions that serve them.”

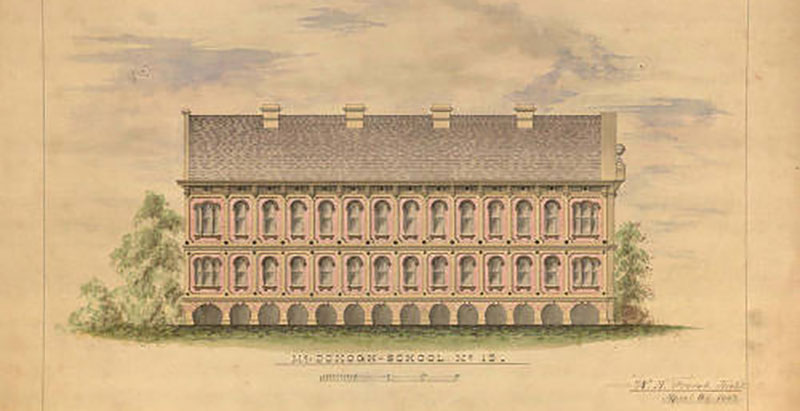

Among Louisiana plantation owners in the early 1800s, McDonogh was considered both odd and benevolent. A miser who had few friends, at one point he was the nation’s largest landowner, a feat he accomplished in part by renting houses to brothels and then, when well-heeled neighbors moved out, buying adjacent properties for a song. He sometimes allowed his slaves to buy their freedom, although he believed that once emancipated, they should be sent to Liberia.

McDonogh left half his estate to the city of New Orleans, to be used to open public schools for both Black and white children. He wanted the students to plant flowers around his grave on his birthday, leading to the creation of a holiday, Founder’s Day. It was celebrated each year until 1954, when Black New Orleanians — whose children were forced to wait in the heat until white children had placed their bouquets — protested and the holiday was eliminated.

There is no complete record of the schools opened in his name, though there have been at least 40. But contrary to McDonogh’s instructions, the city used his bequest at first to open schools only for white children. His money also was used to fund the Confederate Army’s defense of the city during the Civil War.

Half a century passed before the Black community was finally able to get a public high school for its children. In 1917, white students attending McDonogh 13 moved into a newer, nicer building, and Black students moved in. The school was renamed McDonogh 35 — it’s where Hess teaches today, in a new, $59 million building dedicated in 2015. Throughout the decades, McDonogh 35 has been a center for academic excellence, says historian Stern: “For years, the Who’s Who of Black New Orleans came through it.”

Though most have been renamed, McDonogh school buildings still stand throughout the city, his name a permanent part of some facades. McDonogh 35 is one of two that still bear his name; the other is McDonogh 42, part of the same network of schools, InspireNOLA Charter Schools.

As this summer’s protests of police violence against Black people swept the country, InspireNOLA’s leaders announced they had asked NOLA Public Schools to take McDonogh’s name off 42 but not 35. The historical roots — entwined but distinct — of the disparate requests are the subject of one of the hardest lessons Hess teaches.

McDonogh’s legacy is not something most of the city’s students learn about, much less in any depth, in part because there are few teachers of African-American studies. Hess says he doesn’t know of any others outside InspireNOLA schools.

Like generations of his family, Hess expected to graduate from McDonogh 35. But Hurricane Katrina forced his relocation to a mostly Black high school in Houston, where he was exposed to African-American history for the first time. Understanding the magnitude of what he hadn’t been taught propelled Hess to become a teacher.

A former history and social studies teacher who sits on the board of the East Baton Rouge Parish Public Schools, Dadrius Lanus says Black perspectives are rare in U.S. social studies and history lessons in general, but Louisiana’s standards — the specific pieces of knowledge students are expected to learn — are particularly weak.

What material is covered is typically divorced from local context, says Lanus. “If you go to Massachusetts, I guarantee you those students are learning about Boston,” he says. But connections between Louisiana’s brutal racial history and local culture? “It’s a taboo issue.”

As a teacher, Lanus took his students to former plantations. Disciplinary issues in his classes plummeted and engagement rose. “When you ask students why they’re not learning, it’s because they’re bored,” he says. “The way to change [student] engagement would be to change the curriculum to something they connect with, something that’s relevant.”

But U.S. teachers, and particularly the 80 percent who are white, are no more comfortable talking about race than anyone else who was educated in American schools. “When we’re talking about slavery and Black Lives Matter and where that comes from in history, a lot of teachers don’t feel equipped to take that on,” says Bethany Jay, a professor of history at Salem State University in Massachusetts, who trains history teachers.

“Slavery usually emerges as a real topic in the 1830s with westward expansion and as an economic and political issue, and then it goes away until the Civil War, when it’s magically solved,” she says. “They never deal with slavery as a lived experience.”

Broadening academic standards nationwide would be one way to deal with that, but that’s a politicized, uphill battle. Easier, Jay and Lanus say, to create resources incorporating diverse voices for teachers of history, social studies and other subjects to use to create lessons that go further.

To that end, Jay was one of a team of scholars who contributed to “Teaching Hard History,” an effort by the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance project. In addition to essays on the problematic way slavery has been handled in schools, the group created teacher training materials and classroom resources for all grades.

“We’re really not understanding American history if we’re not studying the whole, rich cast of people who were a part of it,” she says.

Lanus echoes the point, adding that it’s not just Black voices that are missing. “This isn’t just African-American students; this is about students who are Muslim or homosexual or transgender,” he says. “Those are things we can’t have a discussion about.”

https://twitter.com/briandelancey/status/1271950423172231173?s=20

School had been out in New Orleans for two weeks when protests began sweeping the country. A statue of McDonogh was wrenched from its stand in a park and dropped into the Mississippi River — later to be fished back out and hidden.

What now stands where the John McDonough bust used to be in Duncan Plaza. Today, protesters took down the statue and threw it into the Mississippi River. McDonough was a white slave owner with ties to New Orleans @WWLTV #BeOn4 pic.twitter.com/EiR207V9Q6

— Andrés Fuentes (@news_fuentes) June 14, 2020

Hess imagines that when McDonogh 35 reopens in August, the intensity of students’ feelings about his classes will be magnified.

All summer, hard questions have been landing in his email inbox. He can hear his past lessons behind them.

How can you tell whether a business with a Black Lives Matter sign really supports racial justice, or just wants to keep Black people’s money flowing?

That student, Hess is confident, took in the point of lessons on the power of Black Civil Rights-era boycotts of the bus system in Alabama and businesses on New Orleans’ Dryades Street.

What changed with the killing of George Floyd by police? What made the protests this time different from Alton Sterling? Trayvon Martin? Sandra Bland?

But also, Why hasn’t anything changed? Why is this still going on?

He may not have those answers, but Hess is proud that his kids are connecting their past to the present, and maybe even a better future.

“It’s very like Black people to take something used against us and make it something to be proud of,” he says. “It’s on us now to make decisions.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)