100 Days Into His Tenure at Scandal-Weary DC Schools, New Chancellor Lewis Ferebee Promises to ‘Move at the Speed of Trust’

Clarification appended May 3

Washington, D.C.

Lewis Ferebee is described by news articles and those who’ve worked with him as Zen-like, soft-spoken, and “calm, cool and collected.”

Or, as Dunbar High School senior Ciata Lattisaw, whom he met during a recent public engagement blitz, summed it up, “He’s a pretty chill dude.”

But it’s this chilled-out quality that may make him well-suited to succeed in Washington, where public officials and parents are weary of a school system hit by back-to-back scandals last year, including the revelation that students are graduating despite missing substantial class time. His predecessor, Antwan Wilson, resigned after just a year on the job after bypassing the city’s lottery system to get his daughter a place in a highly sought-after high school.

“I think there is a lot of work to do to regain the trust that our system is headed in the right direction,” said David Grosso, the chair of the D.C. Council’s education committee.

Julie Pergola, the parent of two children, one in a DCPS elementary school and the other in a charter middle school, said the district feels chaotic.

“It feels very messy. There’s just been so much change. It’s hard to know what’s going on,” she told The 74 at a public meet and greet with the new chancellor in late March.

Ferebee, on the job 100 days as of this week, has met that skepticism head-on with a storm of public engagement, from eight “Ferebee Fridays” to meet the public at venues across the city, to visits to 45 of the 115 DCPS schools, including all 21 of its high schools and all stand-alone middle schools, by May 1.

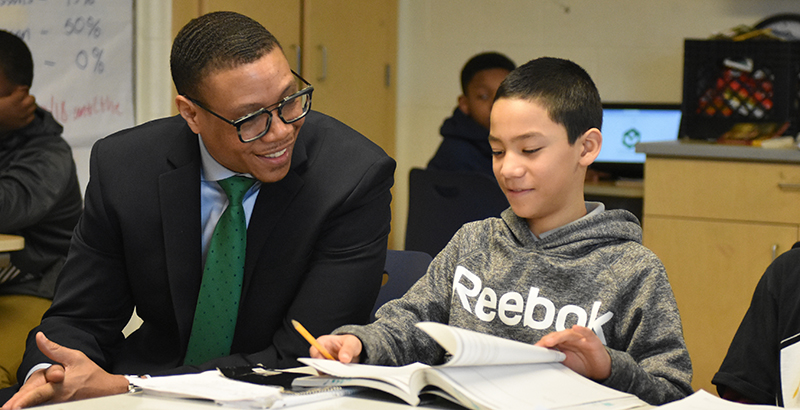

In four school visits accompanied by The 74, Ferebee sat in on classes ranging from bilingual eighth-grade science to fourth-grade reading to a government class debating gentrification in Washington. He mostly sat quietly, asking questions of students and occasionally taking part in larger discussions. But Ferebee, a former middle school principal, did take the opportunity to guest-teach a lesson on mean, median and mode in Bryan Burt’s math class at Alice Deal Middle School.

That public engagement is deliberate.

“You can only move at the speed of trust,” Ferebee told The 74 in an interview.

Although it may switch to a different format, his public visibility will continue, he said. “I think it would be a misstep for me to do extensive engagement in this short period of time and then assume I’m done. I think that work needs to continue.”

Nominated by Mayor Muriel Bowser in late 2018, Ferebee, who shepherded some big changes during his tenure in Indianapolis, at first faced skepticism from some members of the D.C. council who questioned whether those reforms actually led to better test scores or graduation rates for students.

Better outcomes for students is the No. 1 job of the chancellor in D.C., which, despite a growing graduation rate and better standardized test scores in recent years, still faces consistent achievement gaps.

One skeptic was Councilmember Robert C. White, who initially voted “present” rather than yes on Ferebee’s nomination. In a conversation after that vote, Ferebee pledged to White that he’d address teacher turnover, which is highest at already-struggling schools, and the district’s teacher evaluation system, which effectively ended tenure and reduced union influence. Those conversations will happen in conjunction with the Washington Teachers Union. That gave White the confidence that the new chancellor “would be willing to shake up the status quo,” he said via email.

Ferebee eventually got unanimous approval from the 13-member council.

The new chancellor’s cool demeanor and emphasis on public engagement are even more important given the contentious history of education reform in D.C. It began in 2007 with then-Chancellor Michelle Rhee, the first appointed under mayoral control. While successful, she seemed to shun the need for consensus and community engagement when making big changes, eventually appearing on the cover of Time magazine with a broom. The dramatic reforms were blamed in part for the loss of the mayor who appointed her, Adrian Fenty.

“Temperament is important in D.C., given the pace of change over the past decade, given some of the rhetorical battles,” said Thomas Toch, a longtime education writer and advocate who is currently director at the think tank FutureEd, which is associated with Georgetown University. “Dr. Ferebee’s inclination to listen, his soft-spoken [personality], are potential assets.”

In a nod to the need for trust and the scandal that took down his predecessor, Ferebee’s high-school-age son, who will move from Indianapolis this summer, has entered the lottery for next school year but will likely attend a zoned neighborhood school wherever the Ferebees permanently settle, the new chancellor said.

The setup is something of a repeat of how Ferebee approached his job in Indianapolis, where he took his time to get to understand local issues before taking on any big changes, said Brandon Brown, CEO of The Mind Trust, an education reform group in the city.

There, it was the adoption of the innovation school model, which garnered criticism from some corners.

“He’s not a flamethrower … He is someone who cares very deeply about the work, and he’s very careful to learn a new context prior to setting a clear vision,” Brown said.

Taking his time

During his time in Indianapolis, Ferebee adopted a menu of school reforms, including more collaboration with charter schools, new high school models and, perhaps most notably, the creation of innovation schools that offer more autonomy than the traditional district model.

Though early results at innovation have been promising, there is some controversy: The first innovation school was a charter takeover of a failing neighborhood school, which sparked dramatic staff turnover. Others have said the innovation school model in Indianapolis destabilizes local schools and ends union protections.

District-wide outcomes for students were mixed, with lower test scores and a widening achievement gap between black and white students, but a higher graduation rate and higher-than-average growth rate on tests at the lowest-achieving schools.

Ferebee was clear in a press conference when his nomination was announced that he wouldn’t “transport strategies from Indianapolis,” and so far, that’s proving to be true.

His early policy priorities here are far from revolutionary and seem unlikely to attract the kind of public acrimony that often comes with big education changes: technology upgrades, like faster internet connections and a laptop or other device for every student, and working to expand pre-K classrooms and improve attendance in those early years.

He’s also committed to working with the Washington Teachers Union on the IMPACT evaluation system, the Rhee-era program that rates teachers in part on student performance on standardized tests and offers substantial bonuses for those rated highly effective. Teacher turnover in the district is slightly higher than the national average and those of comparable big-city districts.

Longer-term, expect “some work that will be dramatically different” in secondary schools, he said. That’s already started, with a student guide to college, career and graduation, released last week, that provides personalized information on where students are in their path toward graduation.

Down the road, the work on secondary education is likely to mean new career and technical education options, including career exploration in middle school; new dual credit and higher ed opportunities for high schoolers; and more supports for DCPS graduates in college, Ferebee said.

He also wants to work on funding, with “more equitable and transparent allocation of resources” a “clear priority.”

DCPS gets money from the city on a per-pupil basis, then allocates funding to individual schools on a “comprehensive staffing model” that pays for the number of staff needed based on enrollment and whether the campus is an elementary, middle or high school. The city provides additional grant dollars for “at-risk” students, such as those from low-income families or students who are homeless or in the foster care system. An early audit of those “at-risk” funds found that they’ve gone to fund things like arts teachers that should be paid for via other funding streams.

Though the latest budget proposal includes a guide to help parents decipher the budget, and more data about how money is allocated to schools will be released later this spring, the issue of budget transparency has set Ferebee on the path to what could be his first fight with the D.C. Council.

Grosso, the council’s education committee chair, is sponsoring a bill that would make the DCPS budget process more transparent and give school leaders more control over funding.

Although Ferebee agrees with the need to focus on the problem, he wants time to work on it himself before the council steps in.

“I worry that oftentimes there’s some unintended consequences of trying to legislate your way to a solution. So I would hope that DCPS would be given the opportunity to do its own analysis and make a recommendation,” he said.

Beyond this potential disagreement — which will come to a head later this summer when the council considers the bill — Grosso is complimentary of Ferebee, calling him someone who’s in the job for the right reasons and is taking his time to learn the dynamics of the position.

“He also came across as somebody who was willing to learn from his mistakes, which is important to me in this type of work, because it’s a constant shift,” Grosso said.

Ferebee, who agreed with Grosso’s assessment, said missteps earlier in his career had taught him “how important the engagement process is when you’re thinking about redesign or shifting the school model or some dramatic school improvement effort.”

In Indianapolis, Ferebee pressed some initiatives relatively soon after taking office, and “when you take on that amount of change that quickly, there will always be some pushback,” Brown said.

In particular, he added, the original process for setting up innovation schools “wasn’t as transparent and didn’t have as many opportunities to engage the community as he knew he needed.”

Ferebee plans to take that lesson into account when working on school turnaround under the Every Student Succeeds Act. Low-rated schools will get “a suite of options” that school leaders can pick from and a “much longer runway” with more community engagement.

“You have to take time to do that meaningful level of engagement to get the level of ownership you need to really make those transformational efforts come to life,” he said.

Note: This story has been updated to clarify how DCPS allocates funding to individual schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)