Arne Duncan, Obama’s Former Secretary of Education, Just Wrote a Memoir. Here Are 7 Key Highlights

Arne Duncan, the long-standing secretary of education under Barack Obama, has taken a page from the former president’s playbook and penned his own memoir.

How Schools Work weaves through the Chicago native’s early years in the Windy City, where he volunteered at his mother’s afterschool children’s center and later headed the behemoth Chicago Public Schools district, before zeroing in on his tenure as U.S. education secretary from 2009 to 2015. Throughout, Duncan offers a personal account of rolling out a spate of notable — albeit controversial — initiatives, such as a teacher evaluation overhaul and the widespread implementation of Common Core standards via the federal Race to the Top (RTT) grant program.

The nature of his legacy, though, depends largely on whom you ask. Although he stepped down amid record-high U.S. graduation rates and record-low dropout rates, some of his reforms generated bipartisan pushback. Others, such as the $7 billion revamp of the School Improvement Grants (SIG) program, which received next to no mention in the memoir, didn’t yield the desired results. Supporters consider him a champion of the reform movement; critics, which included teachers unions and many conservatives, balked at his posture as a “national school superintendent.”

Here are some of the highlights from the book:

Here are some of the highlights from the book:

1 When Duncan realized the education system was ‘failing’ children

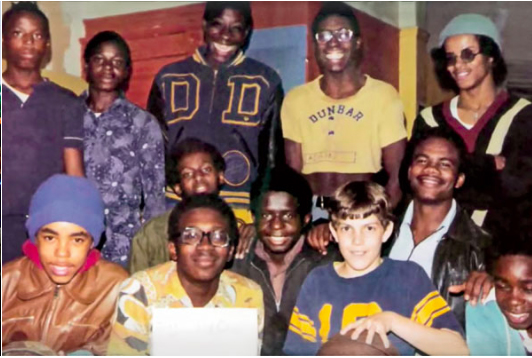

In July 1986, the summer before his senior year of college at Harvard University, Duncan was volunteering at his mother’s afterschool children’s center in Chicago. In walked Calvin Williams, a familiar face and rising high school senior seeking tutoring for the ACT. Williams was destined for greatness, Duncan remembered: A “good” kid and aspiring professional basketball player who “stayed out of trouble” and regularly made the B honor roll at school.

But none of that mattered. Duncan realized that “Calvin struggled to read and could barely form a proper sentence,” he wrote. “His ability to craft a cohesive thought using written language was nonexistent. I wasn’t an expert, but if I had to guess… [he] could read and write at a second- or third-grade level.” The most “insidious” part, Duncan continued, was that Williams was genuinely unaware of how far behind he was.

The experience convinced Duncan that the education system was “failing” its children. His mission thereafter became “all about closing the achievement gap between where I grew up and where Calvin grew up.” It informed his calls as education secretary to reform teacher accountability, expand charter schools, and enact higher, shared state standards.

Overall, the white-black achievement gap has improved since 2003, according to National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) data. However, eight states — including Washington state, Alaska and Ohio — have slid backward, and the achievement gap for eighth-graders actually increased slightly between 2013 and 2015.

2 The bumpy rise of Race to the Top and the Common Core

Race to the Top was Duncan and the Obama administration’s brainchild to raise education standards across the U.S. If states wanted a shot at cashing in on the $4.35 billion grant program, they had to submit plans for ambitious yet comprehensive education reforms. They were pressed to tie teacher performance reviews to standardized testing results, and they had to adopt high-quality, college- and career-ready standards, such as the Common Core.

The three-phase competition, on the tail of 2008’s crippling recession, saw widespread participation, with 45 states submitting at least one application and 19 taking away $17 million to $700 million each. The Race “changed the education landscape in America,” Duncan wrote, likening it to “a wave breaking across the country.” He touted his department’s use of “carrots” over “sticks” — incentives over threats — and maintained (correctly) that most states have some form of the Common Core still baked into their curricula.

Although Duncan believes it will take time to draw definitive conclusions about its success, studies so far have found that the Race’s central goal remains elusive.

The results of 2017 NAEP scores, for example, “largely highlighted the overall flat trend lines among the nation’s schoolchildren,” according to the National Assessment Governing Board and National Center for Education Statistics. A 2016 study by the American Institutes for Research also maintained there “were no significant differences between RTT and other states in [the] use of RTT-promoted practices over time,” and that “the relationship between RTT and student outcomes was not clear.” Overall, states had slow starts implementing their new policies and “struggled to secure the financial, personnel, and technical resources to support schools with this work,” the Center for American Progress reported.

3 ‘Bare-knuckle politicking,’ everywhere

In Duncan’s perfect world, he’d be far removed from politics. In the book, he quoted Obama saying, “Just do what you think is right for kids, and let me worry about the politics.”

Yet ultimately, there would be many political fights to wage and “bare-knuckle politicking” to handle during his tenure in Washington, Duncan wrote. And some of the first tip-offs came from state legislators during Race to the Top.

First there was New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who Duncan said was “understandably livid” after being three points short of winning $400 million in funding. He’d made a “disparaging” announcement in August 2010 that the education department refused to let Commissioner Bret Schundler submit missing information for the application, when that wasn’t the case. Then there was Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who — despite Duncan and his team’s endeavors to make the competition bipartisan and fair — called him in early 2012 to ask, “Are we still going to get our money?” As a new Republican governor replacing a Democrat, Kasich was skeptical that the education department would fulfill its funding promises.

“I know all this stuff is about politics,” he’d reportedly told Duncan. “I don’t live under a rock.”

But one exchange Duncan will “never forget” was with Republican Sen. Lamar Alexander from Tennessee, which had nabbed one of the first Race to the Top grants. Alexander considered tying teacher evaluations to test scores “the holy grail” of education reform. But he told Duncan he couldn’t support implementing higher standards.

“I was stunned,” Duncan wrote. “Senator Alexander’s stance was one of the least principled things I’d ever heard from a politician, and it showed zero political courage.”

The critique goes both ways. While Alexander considers Duncan “one of the president’s best appointments,” he and Obama’s former education secretary don’t see eye-to-eye on the federal government’s role in setting education policy. “If we had a national school board, Arne would be a great chairman,” Alexander, a former education secretary himself under the first President Bush, told Politico. “But Americans don’t want a national school board. He doesn’t seem to understand that.”

Only 36 percent of Americans think the federal government should play the largest role in setting school standards, according to a 2017 Education Next survey. This shift is evident in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the federal education law that replaced No Child Left Behind in 2015 and gave states considerable autonomy over education initiatives.

4 The case for bolstered teacher accountability

A good teacher is “a kid’s best bet” in life, Duncan wrote. He knows because he’s seen it.

Years ago in Chicago, he’d met Kerrie, an African-American boy who’d been abandoned by his mother and raised by a tough-loving, “hard-nosed” grandmother. But at 8 years old, he’d started attending Sue Duncan’s afterschool center. Kerrie would remain involved with the center for nearly 20 years, and he became the second African-American fellow in IBM’s history.

Stories like this, paired with recent studies linking “high-value” teachers with boosted college attendance rates and salaries, strengthened Duncan’s resolve for more teacher accountability — notably through tying teacher evaluations to student performance on standardized tests. While educators deserve “so much more” respect, support, and compensation than they’re currently getting, he wrote, a teacher, “like any professional, should also be able and willing … to demonstrate that she or is is actually good at teaching.”

Race to the Top was his primary vehicle for advancing this agenda, and 43 states required teacher evaluations to incorporate some measure of student growth as of 2015. (That number dropped to 39 states in 2017, and legislation enacted in at least 10 other states has altered or reduced the requirement.)

What’s missing from the book, though, is the full extent of the subsequent backlash. In 2011, educators responded to an open Teacher Appreciation Week letter from Duncan with a letter of their own. They slammed him for “increasing the instability of the profession (and our schools) by promoting policies that tie teachers’ evaluations and continued employment to … measures based on flawed tests.” There is mixed research on whether using student achievement to evaluate educators is effective.

In July 2014, the National Education Association, the largest U.S. teachers union, also called for Duncan’s resignation. In a statement soon after, the American Federation of Teachers claimed Duncan “has failed to bring parents, students, teachers and community members together to improve the quality of public education for all children, and he has promoted misguided and ineffective policies on …. test obsession.”

The following year would usher in a wave of standardized-test boycotts.

5 Addressing his own failures

Duncan clearly remembers the day he “infamously jammed my foot in my mouth” and insulted white suburban moms at a state superintendent’s meeting in November 2013. Criticism was mounting against the Common Core; New York had implemented the standards and weathered plummeting test scores that year as a result.

He’d said, “It’s fascinating to me that some of the pushback is coming from, sort of, white suburban moms who, all of a sudden, their child isn’t as brilliant as they thought they were and their school isn’t quite as good as they thought they were, and that’s pretty scary.” Unsurprisingly, he was railed for his comment (which wasn’t entirely wrong, some pointed out).

The incident, for Duncan, underscored a larger failure of his and the department as a whole: communication — especially when it came to explaining the Common Core and Race to the Top to stakeholders such as teachers, parents, and students.

Duncan found the teachers unions, which are typically “staunchly Democratic,” to be a particularly disappointing adversary.

“These folks, many of whom supported Barack Obama, should have been our natural allies,” he wrote. “But because we were miserable at communicating how and why things were happening, and why they were important, it made things worse. … I’m sorry.”

6 A lesson from Sandy Hook: ‘We don’t value our kids’

Duncan rattles off years, names, data, and minute details throughout his book. But he can’t “remember much” from Dec. 14, 2012, when a man gunned down 20 first-graders and six teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut.

“It was a gray and cold day, befitting the news that I watched with … a small number of staff,” he recalled. “Many cried. Some left the room. … I remember canceling that day’s schedule, and the next day’s as well, and convening a meeting in my office. We sat there dumbstruck.”

Gun violence hits close to home for the former head of Chicago Public Schools. When he led the district, he’d attended funerals for district kids lost to gun violence every two to three weeks. In 2007-08, his last year there, he lost 34 students. “The level of fear that our kids live with every single day is extraordinary,” he wrote. And Sandy Hook affirmed that we’ve chosen “to protect our guns, not our kids. We chose metal over flesh.”

Duncan didn’t delve into the administration’s gun reform efforts, but it’s no secret that Obama faced a divided Congress during his tenure that failed to pass one of more than 100 gun-control measures introduced between January 2011 (when U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords was shot) and January 2017.

Since stepping down, Duncan hasn’t gone silent on gun reform. Quite the opposite: After the latest mass shooting in Santa Fe, Texas, in May — too recent to be included in the book — he piggybacked off a former education department colleague to suggest a nationwide “school boycott.” Two potential dates are Sept. 25, national voter registration day, or just before the Nov. 6 midterm elections.

7 From the basketball court to the classroom, Duncan and Obama’s enduring friendship

Before diving into his journey as education secretary, Duncan took a page or so to describe his friendship with the then-newly-minted president, who also has roots in Chicago.

“Barack and I had been friends for a number of years,” he wrote. “I’d met him through my close friend Craig Robinson, whose sister, Michelle, was then dating Barack. We played pickup games together at the University of Chicago’s Henry Crown Fieldhouse, where, believe it or not, he would sometimes square off against my mom.” Duncan added that professionally, the two had “worked together on education issues when he was both a state and U.S. senator [for Illinois], occasionally visiting schools together.”

Duncan was considered Obama’s “closest friend in the Cabinet,” some media outlets reported. The two regularly played basketball at various federal facilities around D.C. during Obama’s presidency (though Obama now plays golf instead).

Upon Duncan’s resignation, Obama had only glowing words for his colleague: “He’s done more to bring our educational system, sometimes kicking and screaming, into the 21st century than anyone else. America will be better off for what he has done.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)